Charles Yu in The New York Times:

Straw poll: Who thinks we’re living in the Matrix?

On the one hand, are we really to believe a single human is responsible for the body of work — entertaining, brilliant, immense — that Neal Stephenson has produced over the past quarter-century? Turning out thousand-page novels every couple of years? It seems much more likely that a computer is behind all of this. On the other hand, have you read Neal Stephenson? His mind is capable of going places no one else has ever imagined, let alone rendered in photorealist prose. And he doesn’t just go to those places; he takes us with him. The very fact of Stephenson’s existence might be the best argument we have against the simulation hypothesis. His latest, “Fall; or, Dodge in Hell,” is another piece of evidence in the anti-Matrix case: a staggering feat of imagination, intelligence and stamina. For long stretches, at least. Between those long stretches, there are sections that, while never uninteresting, are somewhat less successful. To expect any different, especially in a work of this length, would be to hold it to an impossible standard. Somewhere in this 900-page book is a 600-page book. One that has the same story, but weighs less. Without those 300 pages, though, it wouldn’t be Neal Stephenson. It’s not possible to separate the essential from the decorative. Nor would we want that, even if it were were. Not only do his fans not mind the extra — it’s what we came for.

On the one hand, are we really to believe a single human is responsible for the body of work — entertaining, brilliant, immense — that Neal Stephenson has produced over the past quarter-century? Turning out thousand-page novels every couple of years? It seems much more likely that a computer is behind all of this. On the other hand, have you read Neal Stephenson? His mind is capable of going places no one else has ever imagined, let alone rendered in photorealist prose. And he doesn’t just go to those places; he takes us with him. The very fact of Stephenson’s existence might be the best argument we have against the simulation hypothesis. His latest, “Fall; or, Dodge in Hell,” is another piece of evidence in the anti-Matrix case: a staggering feat of imagination, intelligence and stamina. For long stretches, at least. Between those long stretches, there are sections that, while never uninteresting, are somewhat less successful. To expect any different, especially in a work of this length, would be to hold it to an impossible standard. Somewhere in this 900-page book is a 600-page book. One that has the same story, but weighs less. Without those 300 pages, though, it wouldn’t be Neal Stephenson. It’s not possible to separate the essential from the decorative. Nor would we want that, even if it were were. Not only do his fans not mind the extra — it’s what we came for.

In this particular case, the extra stuff is also kind of the point. The mind-melting density of detail in Stephenson’s work can sometimes overwhelm or bog down the narrative, but in “Fall” it is very much in service of the book’s subject: reality, and how it might one day be simulated. How those simulations could be iterated and upgraded over time, through technological progress and at great financial cost, to an arbitrary degree of verisimilitude. How the resources of our “Meatspace” civilization would increasingly become inputs and raw material for the creation and improvement of a digital civilization (“Bitworld”), gradually sucking all of humanity into the Matrix in the process. Exploring the implications and possibilities of this, on a grand and granular scale, plays to Stephenson’s strengths. This is a case of author and substance and story and style all lining up; a series of lenses perfectly arranged to focus the power and precision of Stephenson’s laser-beam intellect.

More here.

In the fall of 1941, during a stint as a visiting faculty member at the University of Michigan, the poet W.H. Auden offered an undergraduate course of staggering intellectual scope. “Fate and the Individual in European Literature,” as it was titled, is not anything he is known for. Indeed, it is a sad reflection on the preoccupations of literary biography that, while we know far more than any sane person would ever want to know about Auden’s desperately unhappy love life, we know little about the origins or trajectory of this remarkable course. It is mentioned only in passing in some of the biographical accounts of Auden’s life and in a few testimonials from students who took the course (including Kenneth Millar, better known by his detective-fiction pseudonym Ross McDonald). Otherwise, it has gone largely unnoticed or unremarked upon.

In the fall of 1941, during a stint as a visiting faculty member at the University of Michigan, the poet W.H. Auden offered an undergraduate course of staggering intellectual scope. “Fate and the Individual in European Literature,” as it was titled, is not anything he is known for. Indeed, it is a sad reflection on the preoccupations of literary biography that, while we know far more than any sane person would ever want to know about Auden’s desperately unhappy love life, we know little about the origins or trajectory of this remarkable course. It is mentioned only in passing in some of the biographical accounts of Auden’s life and in a few testimonials from students who took the course (including Kenneth Millar, better known by his detective-fiction pseudonym Ross McDonald). Otherwise, it has gone largely unnoticed or unremarked upon. “What was once considered catastrophic warming now seems like a best-case scenario,” Mr Alston said.

“What was once considered catastrophic warming now seems like a best-case scenario,” Mr Alston said. Readers who have followed several incarnations of my blogs (like

Readers who have followed several incarnations of my blogs (like  There are at least four Robert Blys. One is the poet of pure lyrics like the ones I have quoted. Then there is Bly the political poet of the Vietnam War years. After his political and antiwar poetry, Bly turned to the self-help or human potential movement. His book Iron John: A Book about Men, was a best seller, and Bly became a guru of the men’s movement. And there is at least one more Bly: the polemicist. After service in the Navy, graduation from Harvard and Iowa and a few years in New York, Bly settled in rural Minnesota where, in the tradition of poets who used their magazines to advance their views, like T. S. Eliot with The Criterion and John Crowe Ransom with the Kenyon Review, he edited his fiercely polemical magazine, The Fifties (later, predictably enough, The Sixties and The Seventies). Warmly loyal to his friends, Bly was also ready to attack, sometimes viciously, those whose approach to poetry did not agree with his.

There are at least four Robert Blys. One is the poet of pure lyrics like the ones I have quoted. Then there is Bly the political poet of the Vietnam War years. After his political and antiwar poetry, Bly turned to the self-help or human potential movement. His book Iron John: A Book about Men, was a best seller, and Bly became a guru of the men’s movement. And there is at least one more Bly: the polemicist. After service in the Navy, graduation from Harvard and Iowa and a few years in New York, Bly settled in rural Minnesota where, in the tradition of poets who used their magazines to advance their views, like T. S. Eliot with The Criterion and John Crowe Ransom with the Kenyon Review, he edited his fiercely polemical magazine, The Fifties (later, predictably enough, The Sixties and The Seventies). Warmly loyal to his friends, Bly was also ready to attack, sometimes viciously, those whose approach to poetry did not agree with his. The claim to appreciate a film exclusively on pure merit has always been spurious, for it disavows how thoroughly the very notions of achievement and relevance are shaped by power, generally to the detriment of those who have historically been excluded from the practices and institutions that build canons and criteria. There are only five films by women out of some 150 titles in the BFI Classics book series, but not because women have made no great films. Echoing filmmaker Lis Rhodes, who asked “Whose history?” it is now vital to query, “Whose classics?”

The claim to appreciate a film exclusively on pure merit has always been spurious, for it disavows how thoroughly the very notions of achievement and relevance are shaped by power, generally to the detriment of those who have historically been excluded from the practices and institutions that build canons and criteria. There are only five films by women out of some 150 titles in the BFI Classics book series, but not because women have made no great films. Echoing filmmaker Lis Rhodes, who asked “Whose history?” it is now vital to query, “Whose classics?” There are many conclusions to be drawn from the last seven months in France, but one seems unavoidable: a great many people—a majority, perhaps: silent, moral or whatever you want to call it—just don’t like Emmanuel Macron and the world he stands for. It’s only partially misleading to speak of this majority in the aggregate. There are certainly those who want to recreate the cultural makeup of some bygone France. Some of them hate immigrants and others are anti-Semitic. Still others just don’t like the cocky cosmopolitanism of a supposedly new type of elite that casts itself as modern and tolerant and is all the more self-assured because of it. But these are the shadow actors seeking to exploit a far more legitimate and widespread anger. One doesn’t need to be a pollster to pick apart what it really means when, in late December, 70 percent of people in a modern society supported a movement that for several consecutive weekends was rampaging through France’s well-off metropolitan centers and blocking critical road junctures, demanding more economic justice, redistribution, investment in public infrastructure and social services.

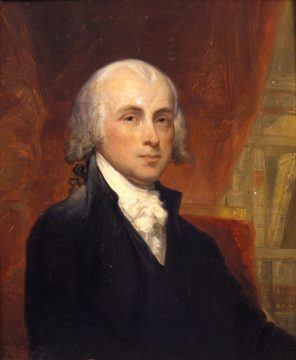

There are many conclusions to be drawn from the last seven months in France, but one seems unavoidable: a great many people—a majority, perhaps: silent, moral or whatever you want to call it—just don’t like Emmanuel Macron and the world he stands for. It’s only partially misleading to speak of this majority in the aggregate. There are certainly those who want to recreate the cultural makeup of some bygone France. Some of them hate immigrants and others are anti-Semitic. Still others just don’t like the cocky cosmopolitanism of a supposedly new type of elite that casts itself as modern and tolerant and is all the more self-assured because of it. But these are the shadow actors seeking to exploit a far more legitimate and widespread anger. One doesn’t need to be a pollster to pick apart what it really means when, in late December, 70 percent of people in a modern society supported a movement that for several consecutive weekends was rampaging through France’s well-off metropolitan centers and blocking critical road junctures, demanding more economic justice, redistribution, investment in public infrastructure and social services. In the greatest of the Federalist Papers, Number 10, James Madison explicitly pointed out the connection between liberty and inequality, and he explained why you can’t have the first without the second. Men formed governments, Madison believed (as did all the Founding Fathers), to safeguard rights that come from nature, not from government—rights to life, to liberty, and to the acquisition and ownership of property. Before we joined forces in society and chose an official cloaked with the authority to wield our collective power to restrain or punish violators of our natural rights, those rights were at constant risk of being trampled by someone stronger than we. Over time, though, those officials’ successors grew autocratic, and their governments overturned the very rights they were supposed to protect, creating a world as arbitrary as the inequality of the state of nature, in which the strongest took whatever he wanted, until someone still stronger came along.

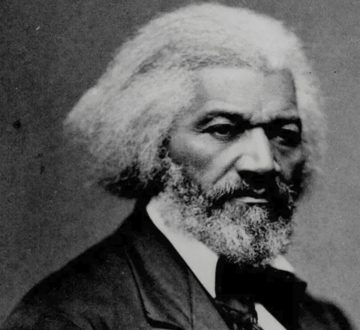

In the greatest of the Federalist Papers, Number 10, James Madison explicitly pointed out the connection between liberty and inequality, and he explained why you can’t have the first without the second. Men formed governments, Madison believed (as did all the Founding Fathers), to safeguard rights that come from nature, not from government—rights to life, to liberty, and to the acquisition and ownership of property. Before we joined forces in society and chose an official cloaked with the authority to wield our collective power to restrain or punish violators of our natural rights, those rights were at constant risk of being trampled by someone stronger than we. Over time, though, those officials’ successors grew autocratic, and their governments overturned the very rights they were supposed to protect, creating a world as arbitrary as the inequality of the state of nature, in which the strongest took whatever he wanted, until someone still stronger came along. I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day? A few years ago the melody for this song came to me in a dream. I woke up from a nap, and as I took a stroll down a California beach, the song structure began to assemble itself. I was there to see a lover for the last time and say goodbye. But in that dream I had decided to move there instead, close to the ocean, abandoning my plans to attend graduate school in Islamic studies, back on the East Coast. In those days, I was consumed by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s recordings. Melodies often dance across my dreams, and back then, each was steeped in the heat and hue of his music.

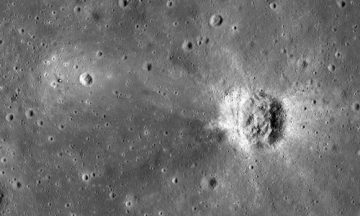

A few years ago the melody for this song came to me in a dream. I woke up from a nap, and as I took a stroll down a California beach, the song structure began to assemble itself. I was there to see a lover for the last time and say goodbye. But in that dream I had decided to move there instead, close to the ocean, abandoning my plans to attend graduate school in Islamic studies, back on the East Coast. In those days, I was consumed by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s recordings. Melodies often dance across my dreams, and back then, each was steeped in the heat and hue of his music. On 20 July 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin landed on the Moon while Michael Collins orbited in the command module Columbia. “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed” became one of the most iconic statements of the Apollo experience and set the stage for five additional Apollo landings.

On 20 July 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin landed on the Moon while Michael Collins orbited in the command module Columbia. “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed” became one of the most iconic statements of the Apollo experience and set the stage for five additional Apollo landings. I once had a friend named Alice who suddenly decided to attain optimum physical fitness. She committed to a strict regime and almost instantly achieved extraordinary results.The trouble was that she spent so much time exercising that she neglected her friendships, abandoned her hobbies, and forfeited all occasions for socialising. She pursued health at the expense of everything else she valued.

I once had a friend named Alice who suddenly decided to attain optimum physical fitness. She committed to a strict regime and almost instantly achieved extraordinary results.The trouble was that she spent so much time exercising that she neglected her friendships, abandoned her hobbies, and forfeited all occasions for socialising. She pursued health at the expense of everything else she valued. A Forest Service report published last year found that across the U.S., populated areas lost about 175,000 acres of trees per year between 2009 and 2014, or approximately 36 million trees per year. Forty-five states had a net decline in tree cover in these areas, with 23 of those states experiencing significant decreases. Meanwhile, urban regions showed a particular decline, along with an increase in what the researchers call “impervious surfaces” – in other words, concrete.

A Forest Service report published last year found that across the U.S., populated areas lost about 175,000 acres of trees per year between 2009 and 2014, or approximately 36 million trees per year. Forty-five states had a net decline in tree cover in these areas, with 23 of those states experiencing significant decreases. Meanwhile, urban regions showed a particular decline, along with an increase in what the researchers call “impervious surfaces” – in other words, concrete. The inhabitants of Westeros and Essos repeatedly face versions of a classic moral dilemma: When is it morally permissible to cause harm in order to prevent further suffering? Philosophers have debated moral dilemmas like this for over a thousand years. “Utilitarian” theories say that all that matters for morality is maximizing good consequences for everyone overall, while “deontological” theories say that some actions are just wrong, even if they have good consequences. The tension between deontological and utilitarian ethics can be seen in the origin story of Jaime Lannister’s sobriquet “Kingslayer”: When the “Mad King” Aerys Targaryen orders for the entire city to be burned, massacring the many thousands of citizens that live there, Jaime violates his sacred oath to protect and serve his lord and instead slits the king’s throat. Utilitarian theories would praise Jaime’s decision to kill the Mad King, because it saves many thousands of lives, while deontological theories would prohibit killing one to save many others.

The inhabitants of Westeros and Essos repeatedly face versions of a classic moral dilemma: When is it morally permissible to cause harm in order to prevent further suffering? Philosophers have debated moral dilemmas like this for over a thousand years. “Utilitarian” theories say that all that matters for morality is maximizing good consequences for everyone overall, while “deontological” theories say that some actions are just wrong, even if they have good consequences. The tension between deontological and utilitarian ethics can be seen in the origin story of Jaime Lannister’s sobriquet “Kingslayer”: When the “Mad King” Aerys Targaryen orders for the entire city to be burned, massacring the many thousands of citizens that live there, Jaime violates his sacred oath to protect and serve his lord and instead slits the king’s throat. Utilitarian theories would praise Jaime’s decision to kill the Mad King, because it saves many thousands of lives, while deontological theories would prohibit killing one to save many others.

Now the raucousness begins in earnest, as Ives renders the Independence Day parade—a drunken, lurching revel with horses on the loose and church bells clanging and a fife-and-drum corps playing intentionally off-key (recalling those lusty if decidedly amateurish New England bands Ives knew so well from his youth). There are quotations galore, some 15 of them, from such popular tunes as “Battle Cry of Freedom,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Yankee Doodle,” “Reveille,” “Marching Through Georgia,” and “Dixie,” in addition to “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” which the trombones deliver with gusto, though many of the tunes are distorted, distended, or truncated. All of these fragments furiously collide with each other, creating an exhilarating swirl, a feeling of polyrhythmic, harmonic chaos. The underlying philosophy here is a democratic ideal, that everything has its place in a piece of music: high art and low, consonance and dissonance, simplicity and mind-boggling complexity—everything goes. So complicated is the score that a second conductor is needed (in some performances, even a third). And in truth, Ives himself never knew if he’d ever hear this work performed. As he later wrote, “I remember distinctly, when I was scoring this, that there was a feeling of freedom as a boy has, on the Fourth of July, who wants to do anything he wants to do. … And I wrote this, feeling free to remember local things, etc, and to put [in] as many feelings and rhythms as I wanted to put together. And I did what I wanted to, quite sure that the thing would never be played, and perhaps could never be played.”

Now the raucousness begins in earnest, as Ives renders the Independence Day parade—a drunken, lurching revel with horses on the loose and church bells clanging and a fife-and-drum corps playing intentionally off-key (recalling those lusty if decidedly amateurish New England bands Ives knew so well from his youth). There are quotations galore, some 15 of them, from such popular tunes as “Battle Cry of Freedom,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Yankee Doodle,” “Reveille,” “Marching Through Georgia,” and “Dixie,” in addition to “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” which the trombones deliver with gusto, though many of the tunes are distorted, distended, or truncated. All of these fragments furiously collide with each other, creating an exhilarating swirl, a feeling of polyrhythmic, harmonic chaos. The underlying philosophy here is a democratic ideal, that everything has its place in a piece of music: high art and low, consonance and dissonance, simplicity and mind-boggling complexity—everything goes. So complicated is the score that a second conductor is needed (in some performances, even a third). And in truth, Ives himself never knew if he’d ever hear this work performed. As he later wrote, “I remember distinctly, when I was scoring this, that there was a feeling of freedom as a boy has, on the Fourth of July, who wants to do anything he wants to do. … And I wrote this, feeling free to remember local things, etc, and to put [in] as many feelings and rhythms as I wanted to put together. And I did what I wanted to, quite sure that the thing would never be played, and perhaps could never be played.”