Max Nelson at the NYRB:

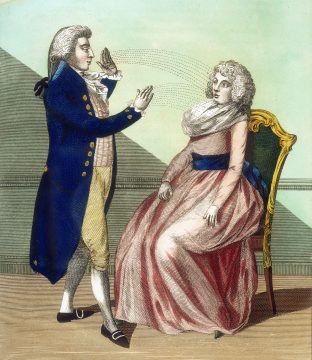

Cynthia Gleason, a weaver at a Rhode Island textile mill, went into her first trance in the fall of 1836. According to her mesmerist, a French sugar planter and amateur “animal magnetist” named Charles Poyen, she had been suffering for years from a mysterious illness; he called it “a very serious and troublesome complaint of the stomach” in one account and “a complicated nervous and functional disease” in another. For months Poyen had been giving lectures insisting that mesmerists like himself had mastered a technique for putting people in somnambulistic trances, curing their diseases, and managing their minds. When Gleason’s physician called him in to make magnetic “passes” over her body with his hands, Poyen wrote in his dubiously self-serving memoirs, she said she’d “defy anyone to put her to sleep in this manner.” But after twenty-five minutes, “her eyes grew dim and her lids fell heavily down.

more here.

At the 1994 reception for the prestigious Kyoto Prize, awarded for achievements that contribute to humanity, the French mathematician André Weil turned to his fellow honoree, the film director Akira Kurosawa, and said: “I have a great advantage over you. I can love and admire your work, but you cannot love and admire my work.”

At the 1994 reception for the prestigious Kyoto Prize, awarded for achievements that contribute to humanity, the French mathematician André Weil turned to his fellow honoree, the film director Akira Kurosawa, and said: “I have a great advantage over you. I can love and admire your work, but you cannot love and admire my work.” Scientists can’t quite agree on how to define “life,” but that hasn’t stopped them from studying it, looking for it elsewhere, or even trying to create it. Kate Adamala is one of a number of scientists engaged in the ambitious project of trying to create living cells, or something approximating them, starting from entirely non-living ingredients. Impressive progress has already been made. Designing cells from scratch will have obvious uses is biology and medicine, but also allow us to build biological robots and computers, as well as helping us understand how life could have arisen in the first place, and what it might look like on other planets.

Scientists can’t quite agree on how to define “life,” but that hasn’t stopped them from studying it, looking for it elsewhere, or even trying to create it. Kate Adamala is one of a number of scientists engaged in the ambitious project of trying to create living cells, or something approximating them, starting from entirely non-living ingredients. Impressive progress has already been made. Designing cells from scratch will have obvious uses is biology and medicine, but also allow us to build biological robots and computers, as well as helping us understand how life could have arisen in the first place, and what it might look like on other planets. In August 1976, The Nation published an essay that rocked the US political establishment, both for what it said and for who was saying it. “

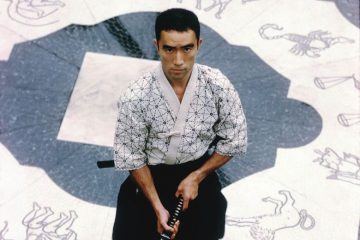

In August 1976, The Nation published an essay that rocked the US political establishment, both for what it said and for who was saying it. “ Star, the short novella Mishima published in November 1960, is little known in Japan, buried as it is under the weight of the grander achievements in the forty-two volumes of his Complete Works. But it is now open to rediscovery thanks to an adroit, colloquial translation into American English by Sam Bett. It offers us a snapshot of a twenty-three-year-old, up-and-coming movie star, Rikio “Richie” Mizuno. Paraded in a string of formulaic films, swooned over by his many female fans, Rikio and the studio who manage him carefully groom his image. When a fan intrudes on the set and disrupts a take to throw herself at “Richie”, the director is at first furious, then ponders whether her intervention couldn’t be built into the script. But she can’t act, so she is quickly cut again and promptly attempts suicide, before the studio spin the story as “Richie” intervening to save her life.

Star, the short novella Mishima published in November 1960, is little known in Japan, buried as it is under the weight of the grander achievements in the forty-two volumes of his Complete Works. But it is now open to rediscovery thanks to an adroit, colloquial translation into American English by Sam Bett. It offers us a snapshot of a twenty-three-year-old, up-and-coming movie star, Rikio “Richie” Mizuno. Paraded in a string of formulaic films, swooned over by his many female fans, Rikio and the studio who manage him carefully groom his image. When a fan intrudes on the set and disrupts a take to throw herself at “Richie”, the director is at first furious, then ponders whether her intervention couldn’t be built into the script. But she can’t act, so she is quickly cut again and promptly attempts suicide, before the studio spin the story as “Richie” intervening to save her life. Now regarded as a towering figure of modern verse, Wallace Stevens was probably better known as an insurance man for much of his adult life. But during a long and comfortable career at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, he also wrote poems that cut to the very heart of existence. Like his near contemporary (and sometimes rival)

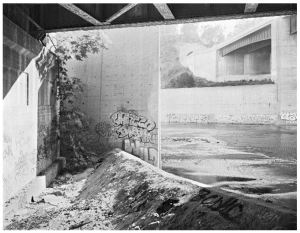

Now regarded as a towering figure of modern verse, Wallace Stevens was probably better known as an insurance man for much of his adult life. But during a long and comfortable career at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, he also wrote poems that cut to the very heart of existence. Like his near contemporary (and sometimes rival)  More urgently, L.A. is the ideal place to tackle the problem of how to write about nature. In the past twenty-five years, the venerable American literature of nature writing has become distressingly marginal. Even my nature-loving and environmentalist friends tell me they never read it. Earnest, pious, and quite allergic to irony: none of these trademark qualities plays well in 2006. But to me, the core trouble is that nature writers have given us endless paeans to the wonders of wildness since Thoreau fled to Walden Pond, but need to tell us far more about our everyday lives in the places we actually live. Perhaps you’re not worrying about the failures of this literary genre as a serious problem. But in my own arm-waving manifesto about L.A. and America, I will proclaim that the crisis in nature writing is one of our most pressing national cultural catastrophes.

More urgently, L.A. is the ideal place to tackle the problem of how to write about nature. In the past twenty-five years, the venerable American literature of nature writing has become distressingly marginal. Even my nature-loving and environmentalist friends tell me they never read it. Earnest, pious, and quite allergic to irony: none of these trademark qualities plays well in 2006. But to me, the core trouble is that nature writers have given us endless paeans to the wonders of wildness since Thoreau fled to Walden Pond, but need to tell us far more about our everyday lives in the places we actually live. Perhaps you’re not worrying about the failures of this literary genre as a serious problem. But in my own arm-waving manifesto about L.A. and America, I will proclaim that the crisis in nature writing is one of our most pressing national cultural catastrophes. If Happy the elephant were allowed to live a natural life in the wild, she would likely spend her days roaming miles of tropical forest and plucking fruit and leaves from trees with the finger-like tip of her trunk. She would have grown up as part of a complex social system, in which elephant calves are doted on by older siblings, cousins, and aunts. By age forty-seven, Happy would likely have already raised multiple calves of her own. She would trumpet with excitement at the other members of her herd and call to potential mates using infrasonic rumbles that travel long distances, inaudible to the human ear.

If Happy the elephant were allowed to live a natural life in the wild, she would likely spend her days roaming miles of tropical forest and plucking fruit and leaves from trees with the finger-like tip of her trunk. She would have grown up as part of a complex social system, in which elephant calves are doted on by older siblings, cousins, and aunts. By age forty-seven, Happy would likely have already raised multiple calves of her own. She would trumpet with excitement at the other members of her herd and call to potential mates using infrasonic rumbles that travel long distances, inaudible to the human ear. Christof Koch, a leading researcher on consciousness and the human brain, has famously called the brain “the most complex object in the known universe.” It’s not hard to see why this might be true. With a hundred billion neurons and a hundred trillion connections, the brain is a dizzyingly complex object. But there are plenty of other complicated objects in the universe. For example, galaxies can group into enormous structures (called clusters, superclusters, and filaments) that stretch for hundreds of millions of light-years. The boundary between these structures and neighboring stretches of empty space called cosmic voids can be extremely complex.1 Gravity accelerates matter at these boundaries to speeds of thousands of kilometers per second, creating shock waves and turbulence in intergalactic gases. We have predicted that the void-filament boundary is one of the most complex volumes of the universe, as measured by the number of bits of information it takes to describe it.

Christof Koch, a leading researcher on consciousness and the human brain, has famously called the brain “the most complex object in the known universe.” It’s not hard to see why this might be true. With a hundred billion neurons and a hundred trillion connections, the brain is a dizzyingly complex object. But there are plenty of other complicated objects in the universe. For example, galaxies can group into enormous structures (called clusters, superclusters, and filaments) that stretch for hundreds of millions of light-years. The boundary between these structures and neighboring stretches of empty space called cosmic voids can be extremely complex.1 Gravity accelerates matter at these boundaries to speeds of thousands of kilometers per second, creating shock waves and turbulence in intergalactic gases. We have predicted that the void-filament boundary is one of the most complex volumes of the universe, as measured by the number of bits of information it takes to describe it. Although Boyle is not in any way connected to the current Psychedelic Renaissance, he has a lot to say about the topic of psychedelic drugs because he experimented with a wide range of psychotropic drugs in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In his own words, he was a “hippie’s hippie.” In the early 1970s, he was “so blissed out and outrageously accoutred that people would stop me on the street and ask me I could sell them some acid.” However, at that time LSD was not actually the novelist’s drug of choice. Boyle preferred various downers and heroin. His first published short story, “The OD & Hepatitis RR or Bust,” is a visceral description of a heroin experience and its aftermath. This story, which was published in the North American Review, helped Boyle get into the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Boyle was certainly fortunate to escape his youth without overdosing. One of Boyle’s nonfictional essays, “This Monkey, My Back” describes how the experience of writing slowly became his habit of choice: “[W]riting is a habit, an addiction, as powerful and overmastering an urge as putting a bottle to your lips or a spike in your arms. Call it the impulse to make something out of nothing, call it an obsessive-compulsive disorder, call it logorrhea.” Boyle also believes that the “experience of creating art — in this case books — resembles a heroin experience. You have a tremendous rush to complete it. But like any habit you have to do it again.” At the moment, Boyle’s healthier form of addiction has produced nine collections of short stories and 17 novels.

Although Boyle is not in any way connected to the current Psychedelic Renaissance, he has a lot to say about the topic of psychedelic drugs because he experimented with a wide range of psychotropic drugs in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In his own words, he was a “hippie’s hippie.” In the early 1970s, he was “so blissed out and outrageously accoutred that people would stop me on the street and ask me I could sell them some acid.” However, at that time LSD was not actually the novelist’s drug of choice. Boyle preferred various downers and heroin. His first published short story, “The OD & Hepatitis RR or Bust,” is a visceral description of a heroin experience and its aftermath. This story, which was published in the North American Review, helped Boyle get into the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Boyle was certainly fortunate to escape his youth without overdosing. One of Boyle’s nonfictional essays, “This Monkey, My Back” describes how the experience of writing slowly became his habit of choice: “[W]riting is a habit, an addiction, as powerful and overmastering an urge as putting a bottle to your lips or a spike in your arms. Call it the impulse to make something out of nothing, call it an obsessive-compulsive disorder, call it logorrhea.” Boyle also believes that the “experience of creating art — in this case books — resembles a heroin experience. You have a tremendous rush to complete it. But like any habit you have to do it again.” At the moment, Boyle’s healthier form of addiction has produced nine collections of short stories and 17 novels. Our lives are full of experiences that, like cause and effect, only run one way. The irreversibility of time, and of life, is an essential part of the experience of being human. But, incongruously, it is not an essential part of physics. In fact, the laws of physics don’t care at all which way time goes. Spin the clock backward and the equations still work out just fine. “The laws of physics at the fundamental level don’t distinguish between the past and the future,” says

Our lives are full of experiences that, like cause and effect, only run one way. The irreversibility of time, and of life, is an essential part of the experience of being human. But, incongruously, it is not an essential part of physics. In fact, the laws of physics don’t care at all which way time goes. Spin the clock backward and the equations still work out just fine. “The laws of physics at the fundamental level don’t distinguish between the past and the future,” says  In a surprising new national survey, members of each major American political party were

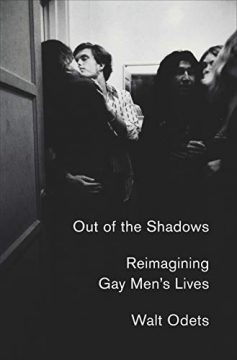

In a surprising new national survey, members of each major American political party were  Though resisted by many queer activists, by 2015 marriage equality had become central to gay and lesbian public life. The post-Obergefell hangover was widespread: If the victory was as total as promised, what work could possibly follow it or be left to do in its wake? Walt Odets’s Out of the Shadows: Reimagining Gay Men’s Lives steps into this confusion with welcome insight and a shift in emphasis. “For gay lives,” Odets writes, “the granting of legal rights and authentic acceptance are two different issues in a society steeped in phobic aversion to real diversity.” To pro-marriage polemicists like Sullivan, gay particularity was attributable to our formal exclusion from mainstream institutions. When gays were no longer treated differently by law, he and others reasoned, we would cease to be different, compelling straights to finally welcome us into the social fold. Odets, a clinical psychologist with thirty years of private practice in the San Francisco Bay Area, airs what may look like dirty laundry to those who harbored such hopes. The overriding emphasis on marriage equality has pressured gays and lesbians to adopt a scrupulous regimen of self-love, turning any lingering shame into its own shameful secret. (One of Odets’s patients, Amado, confesses to having preempted a man’s rejection by telling him, “The more you get to know about me, the less you’ll probably want to know.”) Even among those of his patients—older, financially secure, monogamously partnered gay men—who might appear best positioned to reap its benefits, Obergefell has been no panacea for Sullivan’s “marginalization and pathology.”

Though resisted by many queer activists, by 2015 marriage equality had become central to gay and lesbian public life. The post-Obergefell hangover was widespread: If the victory was as total as promised, what work could possibly follow it or be left to do in its wake? Walt Odets’s Out of the Shadows: Reimagining Gay Men’s Lives steps into this confusion with welcome insight and a shift in emphasis. “For gay lives,” Odets writes, “the granting of legal rights and authentic acceptance are two different issues in a society steeped in phobic aversion to real diversity.” To pro-marriage polemicists like Sullivan, gay particularity was attributable to our formal exclusion from mainstream institutions. When gays were no longer treated differently by law, he and others reasoned, we would cease to be different, compelling straights to finally welcome us into the social fold. Odets, a clinical psychologist with thirty years of private practice in the San Francisco Bay Area, airs what may look like dirty laundry to those who harbored such hopes. The overriding emphasis on marriage equality has pressured gays and lesbians to adopt a scrupulous regimen of self-love, turning any lingering shame into its own shameful secret. (One of Odets’s patients, Amado, confesses to having preempted a man’s rejection by telling him, “The more you get to know about me, the less you’ll probably want to know.”) Even among those of his patients—older, financially secure, monogamously partnered gay men—who might appear best positioned to reap its benefits, Obergefell has been no panacea for Sullivan’s “marginalization and pathology.” The chilling sublimity of the site was undeniable—and discomfiting. Mirroring the debate about anti-wall resistance art, there emerged in the wake of the prototypes’ unveiling a new round of arguments about whether critiquing them risked validating them. “Is it inspired or irresponsible to call Donald Trump’s wall prototypes ‘art’?” That was the headline of a Los Angeles Timesarticle written by the critic Carolina Miranda, who quoted local architect René Peralta: “It would be irresponsible, easy and lazy to consider it as an aesthetic object.” No one had lavished this much attention on the fences that had been built in the mid-2000s; why the sudden interest now? To grant so much exposure to the prototypes—which were never likely to lead to a real wall—was to carry the administration’s water, perpetuating the illusion of progress by raising their visibility.

The chilling sublimity of the site was undeniable—and discomfiting. Mirroring the debate about anti-wall resistance art, there emerged in the wake of the prototypes’ unveiling a new round of arguments about whether critiquing them risked validating them. “Is it inspired or irresponsible to call Donald Trump’s wall prototypes ‘art’?” That was the headline of a Los Angeles Timesarticle written by the critic Carolina Miranda, who quoted local architect René Peralta: “It would be irresponsible, easy and lazy to consider it as an aesthetic object.” No one had lavished this much attention on the fences that had been built in the mid-2000s; why the sudden interest now? To grant so much exposure to the prototypes—which were never likely to lead to a real wall—was to carry the administration’s water, perpetuating the illusion of progress by raising their visibility. T

T One of Simon Henderson’s first decisions after taking over last summer as headmaster of Eton College was to move his office out of the labyrinthine, late-medieval centre of the school and into a corporate bunker that has been appended (“insensitively”, as an architectural historian might say) to a Victorian teaching block. Here, in classless, optimistic tones, Henderson lays out a vision of a formerly Olympian institution becoming a mirror of modern society, diversifying its intake so that anyone “from a poor boy at a primary school in the north of England to one from a great fee-paying prep school in the south” can aspire to be educated there (so long as he’s a he, of course), joyfully sharing expertise, teachers and facilities with the state sector – in short, striving “to be relevant and to contribute”. His aspiration that Eton should become an agent of social change is not one that many of his 70 predecessors in the job over the past six centuries would have shared; and it is somehow no surprise to hear that he has incurred the displeasure of some of the more traditionally minded boys by high-fiving them. What had happened, I wondered as I left the bunker, to the Eton I knew when I was a pupil in the late 1980s – a school so grand it didn’t care what anyone thought of it, a four-letter word for the Left, a source of pride for the Right, and a British brand to rival Marmite and King Arthur?

One of Simon Henderson’s first decisions after taking over last summer as headmaster of Eton College was to move his office out of the labyrinthine, late-medieval centre of the school and into a corporate bunker that has been appended (“insensitively”, as an architectural historian might say) to a Victorian teaching block. Here, in classless, optimistic tones, Henderson lays out a vision of a formerly Olympian institution becoming a mirror of modern society, diversifying its intake so that anyone “from a poor boy at a primary school in the north of England to one from a great fee-paying prep school in the south” can aspire to be educated there (so long as he’s a he, of course), joyfully sharing expertise, teachers and facilities with the state sector – in short, striving “to be relevant and to contribute”. His aspiration that Eton should become an agent of social change is not one that many of his 70 predecessors in the job over the past six centuries would have shared; and it is somehow no surprise to hear that he has incurred the displeasure of some of the more traditionally minded boys by high-fiving them. What had happened, I wondered as I left the bunker, to the Eton I knew when I was a pupil in the late 1980s – a school so grand it didn’t care what anyone thought of it, a four-letter word for the Left, a source of pride for the Right, and a British brand to rival Marmite and King Arthur? In 1972, a young ecologist named Hjalmar Thiel ventured to a remote part of the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ). The sea floor there boasts one of the world’s largest untapped collections of rare-earth elements. Some 4,000 metres below the ocean surface, the abyssal ooze of the CCZ holds trillions of polymetallic nodules — potato-sized deposits loaded with copper, nickel, manganese and other precious ores. Thiel was interested in the region’s largely unstudied meiofauna — the tiny animals that live on and between the nodules. His travel companions — prospective miners — were more eager to harvest its riches. “We had a lot of fights,” he says. On another voyage, Thiel visited the Red Sea with would-be miners who were keen to extract potentially valuable ores from the region’s metal-rich muds. At one point, he cautioned them that if they went ahead with their plans and dumped their waste sediment at the sea surface, it could suffocate small swimmers such as plankton. “They were nearly ready to drown me,” Thiel recalls of his companions.

In 1972, a young ecologist named Hjalmar Thiel ventured to a remote part of the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ). The sea floor there boasts one of the world’s largest untapped collections of rare-earth elements. Some 4,000 metres below the ocean surface, the abyssal ooze of the CCZ holds trillions of polymetallic nodules — potato-sized deposits loaded with copper, nickel, manganese and other precious ores. Thiel was interested in the region’s largely unstudied meiofauna — the tiny animals that live on and between the nodules. His travel companions — prospective miners — were more eager to harvest its riches. “We had a lot of fights,” he says. On another voyage, Thiel visited the Red Sea with would-be miners who were keen to extract potentially valuable ores from the region’s metal-rich muds. At one point, he cautioned them that if they went ahead with their plans and dumped their waste sediment at the sea surface, it could suffocate small swimmers such as plankton. “They were nearly ready to drown me,” Thiel recalls of his companions.