Chanting the Mountains

Say: “Mountains are sacred”

because mountains are born from contracting tectonic plates––

because mountains live on a quarter of the planet’s surface––

because mountains shape local and global climates

Say: “Mountains are sacred”

because mountains nourish trees, animals and food crops––

because mountains house native peoples, minorities, and refugees––

because mountains create corridors for migrating species––

because my family lives on a submerged mountain––

Say: “Mountains are sacred”

because mountains capture moisture from the atmosphere––

because mountains filter aquifers and source rivers––

because mountains provide freshwater for half of humanity

Say: “Mountains are sacred”

because what else do you call places that are always being desecrated

by corporations, armies, and nations––

who clearcut, detonate, drill, mine, extract, and pollute––

who violently remove mountaintops––

who violently remove entire mountains

Say: “Mountains are sacred”

because we say stop!

this is our center of creation–––stop!

this is where we bury and honor our dead––stop!

this is where we pilgrimage, worship, and make offerings––stop!

you are hurting our mountain elders

Say: “Mountains are sacred”

because there once was a mountain here––

because this deep opened wound was once home

Say: “Mountains are sacred” Read more »

Ethan Weinstein in 3:AM Magazine:

Ethan Weinstein in 3:AM Magazine: Astra Taylor in the New York Times:

Astra Taylor in the New York Times: Lenore Palladino in Boston Review, with responses from William Lazonick, Julius Krein, Lauren Jacobs, Michael Lind, Isabelle Ferreras, James Galbraith and Katharina Pistor:

Lenore Palladino in Boston Review, with responses from William Lazonick, Julius Krein, Lauren Jacobs, Michael Lind, Isabelle Ferreras, James Galbraith and Katharina Pistor: Philip Mader, Richard Jolly, Maren Duvendack and Solene Morvant-Roux over at the Institute for Development Studies:

Philip Mader, Richard Jolly, Maren Duvendack and Solene Morvant-Roux over at the Institute for Development Studies: Edit Schlaffer felt as if she was part of history in the making when 60 mothers from this southern region of Germany recently received their MotherSchools diploma from Bavaria’s social minister. Ms. Schlaffer initiated her MotherSchools syllabus nine years ago for women in Tajikistan who were concerned about Islamic extremists recruiting their children. The program has since become a global movement whose goal is to fight extremism not with soldiers, but with mothers. And now, Germany has its first batch of graduates – women with roots from Syria to Algeria. They’ve learned not only how to better detect, and respond to, early signs of radicalization, but also how to better connect with their sons. When Ms. Schlaffer initially met them, the women had tended to be shy, their hands often crossed on their knees and their heads bent down. But on graduation day, donning colorful headscarves and shiny suits, they mingled with top brass politicians in a castle overlooking the Main River here.

Edit Schlaffer felt as if she was part of history in the making when 60 mothers from this southern region of Germany recently received their MotherSchools diploma from Bavaria’s social minister. Ms. Schlaffer initiated her MotherSchools syllabus nine years ago for women in Tajikistan who were concerned about Islamic extremists recruiting their children. The program has since become a global movement whose goal is to fight extremism not with soldiers, but with mothers. And now, Germany has its first batch of graduates – women with roots from Syria to Algeria. They’ve learned not only how to better detect, and respond to, early signs of radicalization, but also how to better connect with their sons. When Ms. Schlaffer initially met them, the women had tended to be shy, their hands often crossed on their knees and their heads bent down. But on graduation day, donning colorful headscarves and shiny suits, they mingled with top brass politicians in a castle overlooking the Main River here. Back in the 1940s, C. S. Lewis remarked on a trend that he saw gaining steam even among some of his better pupils at Oxford: a belief that books penned by the greatest minds of the previous two or three millennia could be grasped only by credentialed professionals. This instinct steered them away from the satisfactions of primary literature and into the swamps of secondary works expounding upon the original sources. “I have found as a tutor in English Literature,” Lewis wrote, “that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about ‘isms’ and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said.” Lewis was not denigrating commentaries; he wrote some formidable ones himself. He was merely making the point that most great writers of the distant past wrote to be read and apprehended by curious minds, not merely to provide fodder for exams and dissertations.

Back in the 1940s, C. S. Lewis remarked on a trend that he saw gaining steam even among some of his better pupils at Oxford: a belief that books penned by the greatest minds of the previous two or three millennia could be grasped only by credentialed professionals. This instinct steered them away from the satisfactions of primary literature and into the swamps of secondary works expounding upon the original sources. “I have found as a tutor in English Literature,” Lewis wrote, “that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about ‘isms’ and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said.” Lewis was not denigrating commentaries; he wrote some formidable ones himself. He was merely making the point that most great writers of the distant past wrote to be read and apprehended by curious minds, not merely to provide fodder for exams and dissertations. About 10 years ago, I began to get impatient with disability studies. The field was still relatively young, but it seemed devoted almost entirely to analyzing how disability was represented – in art, in culture, in politics, et cetera – especially in the case of physical disability. This, I thought, fell short of the field’s promise for literary studies. Where, I wondered, was the field’s equivalent of Epistemology of the Closet, the book in which Eve Sedgwick showed us how to ‘queer’ texts, such that we will never read a narrative silence or lacuna the same way again? Put another way: I wanted a book that showed how an understanding of disability changes the way we read.

About 10 years ago, I began to get impatient with disability studies. The field was still relatively young, but it seemed devoted almost entirely to analyzing how disability was represented – in art, in culture, in politics, et cetera – especially in the case of physical disability. This, I thought, fell short of the field’s promise for literary studies. Where, I wondered, was the field’s equivalent of Epistemology of the Closet, the book in which Eve Sedgwick showed us how to ‘queer’ texts, such that we will never read a narrative silence or lacuna the same way again? Put another way: I wanted a book that showed how an understanding of disability changes the way we read. Ordinary physical theories tell you what a system is and how it evolves over time. Quantum mechanics does this as well, but it also comes with an entirely new set of rules, governing what happens when systems are observed or measured. Most notably, measurement outcomes cannot be predicted with perfect confidence, even in principle. The best we can do is to calculate the probability of obtaining each possible outcome, according to what’s called the Born rule: The wave function assigns an “amplitude” to each measurement outcome, and the probability of getting that result is equal to the amplitude squared. This feature is what led Albert Einstein to complain about God playing dice with the universe.

Ordinary physical theories tell you what a system is and how it evolves over time. Quantum mechanics does this as well, but it also comes with an entirely new set of rules, governing what happens when systems are observed or measured. Most notably, measurement outcomes cannot be predicted with perfect confidence, even in principle. The best we can do is to calculate the probability of obtaining each possible outcome, according to what’s called the Born rule: The wave function assigns an “amplitude” to each measurement outcome, and the probability of getting that result is equal to the amplitude squared. This feature is what led Albert Einstein to complain about God playing dice with the universe. In the spring of 2009, with the battle over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in full swing, President Barack Obama called his aides into the oval office for an unusual meeting. As the New York Times

In the spring of 2009, with the battle over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in full swing, President Barack Obama called his aides into the oval office for an unusual meeting. As the New York Times  I have a practical build. I’m petite, compact. My stomach is tight, small, undemanding. My lungs and my shoulders are strong. I’m not on any prescriptions—not even the pill—and I don’t wear glasses. I cut my hair with clippers, once every three months, and I use almost no makeup. My teeth are healthy, perhaps a bit uneven, but intact, and I have just one old filling, which I believe is located in my lower left canine. My liver function is within the normal range. As is my pancreas. Both my right and left kidneys are in great shape. My abdominal aorta is normal. My bladder works. Hemoglobin 12.7. Leukocytes 4.5. Hematocrit 41.6. Platelets 228. Cholesterol 204. Creatinine 1.0. Bilirubin 4.2. And so on. My IQ—if you put any stock in that kind of thing—is 121; it’s passable. My spatial reasoning is particularly advanced, almost eidetic, though my laterality is lousy. Personality unstable, or not entirely reliable. Age all in your mind. Gender grammatical. I actually buy my books in paperback, so that I can leave them without remorse on the platform, for someone else to find. I don’t collect anything.

I have a practical build. I’m petite, compact. My stomach is tight, small, undemanding. My lungs and my shoulders are strong. I’m not on any prescriptions—not even the pill—and I don’t wear glasses. I cut my hair with clippers, once every three months, and I use almost no makeup. My teeth are healthy, perhaps a bit uneven, but intact, and I have just one old filling, which I believe is located in my lower left canine. My liver function is within the normal range. As is my pancreas. Both my right and left kidneys are in great shape. My abdominal aorta is normal. My bladder works. Hemoglobin 12.7. Leukocytes 4.5. Hematocrit 41.6. Platelets 228. Cholesterol 204. Creatinine 1.0. Bilirubin 4.2. And so on. My IQ—if you put any stock in that kind of thing—is 121; it’s passable. My spatial reasoning is particularly advanced, almost eidetic, though my laterality is lousy. Personality unstable, or not entirely reliable. Age all in your mind. Gender grammatical. I actually buy my books in paperback, so that I can leave them without remorse on the platform, for someone else to find. I don’t collect anything.

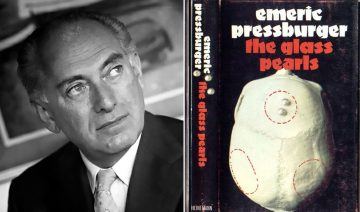

In the aftermath of the dissolution of Pressburger and Powell’s partnership in the late fifties, Pressburger turned to novels. The first, Killing a Mouse on a Sunday, published in 1961, is set during the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and tells the story of a once notorious bandit, now a tired old man living in exile in France who resolves to cross the border back into Spain, despite the danger to his life, to visit his dying mother. In an interview published in the Daily Mail at the time, Pressburger explained that after years of “communal” creativity in the world of film, he wanted to “prove I could do something on my own.” The novel met with favorable reviews, was quickly translated into a dozen languages, and adapted for the big screen in 1964 as Behold a Pale Horse, directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Gregory Peck, Omar Sharif, and Anthony Quinn. (That the film itself died a quick death didn’t really matter.) Everything was set for Pressburger’s second novel to build on this success. Unfortunately, this wasn’t to be. The Glass Pearls, published in 1966, was a much darker, grittier tale about a Nazi war criminal hiding in plain sight in the dingy streets of London’s Pimlico. It garnered one lone review, a damning write-up in the Times Literary Supplement. The book barely sold its initial print run of four thousand copies, immediately sinking without a trace. And yet, despite the reception it received at the time, The Glass Pearls is a truly remarkable work. It deserves to be recognized both for its own virtuosity, and as an important addition to the genre of Holocaust literature.

In the aftermath of the dissolution of Pressburger and Powell’s partnership in the late fifties, Pressburger turned to novels. The first, Killing a Mouse on a Sunday, published in 1961, is set during the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and tells the story of a once notorious bandit, now a tired old man living in exile in France who resolves to cross the border back into Spain, despite the danger to his life, to visit his dying mother. In an interview published in the Daily Mail at the time, Pressburger explained that after years of “communal” creativity in the world of film, he wanted to “prove I could do something on my own.” The novel met with favorable reviews, was quickly translated into a dozen languages, and adapted for the big screen in 1964 as Behold a Pale Horse, directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Gregory Peck, Omar Sharif, and Anthony Quinn. (That the film itself died a quick death didn’t really matter.) Everything was set for Pressburger’s second novel to build on this success. Unfortunately, this wasn’t to be. The Glass Pearls, published in 1966, was a much darker, grittier tale about a Nazi war criminal hiding in plain sight in the dingy streets of London’s Pimlico. It garnered one lone review, a damning write-up in the Times Literary Supplement. The book barely sold its initial print run of four thousand copies, immediately sinking without a trace. And yet, despite the reception it received at the time, The Glass Pearls is a truly remarkable work. It deserves to be recognized both for its own virtuosity, and as an important addition to the genre of Holocaust literature. In August, marine biologists Johnny Gaskell and Peter Mumby and a team of researchers boarded a boat headed into unknown waters off the coasts of Australia. For 14 long hours, they ploughed over 200 nautical miles, a Google Maps cache as their only guide. Just before dawn, they arrived at their destination of a previously uncharted blue hole—a cavernous opening descending through the seafloor. After the rough night, Mumby was rewarded with something he hadn’t seen in his 30-year career. The reef surrounding the blue hole had nearly 100 percent healthy coral cover. Such a find is rare in the Great Barrier Reef, where coral bleaching events in 2016 and 2017 led to headlines

In August, marine biologists Johnny Gaskell and Peter Mumby and a team of researchers boarded a boat headed into unknown waters off the coasts of Australia. For 14 long hours, they ploughed over 200 nautical miles, a Google Maps cache as their only guide. Just before dawn, they arrived at their destination of a previously uncharted blue hole—a cavernous opening descending through the seafloor. After the rough night, Mumby was rewarded with something he hadn’t seen in his 30-year career. The reef surrounding the blue hole had nearly 100 percent healthy coral cover. Such a find is rare in the Great Barrier Reef, where coral bleaching events in 2016 and 2017 led to headlines  The car, wrote the French thinker André Gorz, “supports in everyone the illusion that each individual can seek his or her own benefit at the expense of everyone else”.

The car, wrote the French thinker André Gorz, “supports in everyone the illusion that each individual can seek his or her own benefit at the expense of everyone else”.  Thomas Piketty’s new book

Thomas Piketty’s new book