Moribund

The animals are dying.

All the beautiful women are dying too.

Elizabeth Kolbert writes you can see the sixth

mass extinction unraveling in your own backyard.

Out the fourteenth-story windows of the hotel

I watch as an unraveling of women

pull themselves from a small blue rectangle

to dry their skin. This must be the most

beautiful thing. First, women, and second, women

as a diorama of themselves. In a 1969 lecture available

online, physicist Albert Bartlett tells us, The greatest

shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand

the exponential function. Jenifer Wightman quotes this in

her paper

on bacterial pointillism, a type of painting technique whereby mud

is colonized by pigmented bacteria to produce an evolving color-

field of living pigments, a Rothko-like landscape whose subject is

generations of sequential doublings. Always there is what

scientists call

the background rate of extinction, that little death hum of

one to five

species per year, and today it’s

a thousand to ten thousand times that. They’re dying

before we know they exist. Can you see that? The hotel room rises

fourteen stories, 196 stories, 2,744 stories, and the women in

the pool

are multiplying into a Rothko painting. On the news, I watch

Syrian women haul bundled children through Aleppo’s

smoldering fossil. They are dying, as are their children.

Syrian mothers write appeals followed by farewells

on social media. Final message, one reads. I am very sad

no one is helping us in this world, no one is evacuating me &

my daughter,

goodbye. Blue is the opposite of red, oxygen molecules

binding to hemoglobin as a blue thing exposed

reddens. On the day after Christmas in 2015 the New York Times

posts

a video of a twenty-seven-year-old Muslim woman in Kabul

accused of burning

the Quran. A male mob swells. The policemen stand back as

poles &

bricks are held above her. Then, at a certain velocity, lowered

to break her. It is hundreds of men crying Allahu Akbar

as she whimpers Allahu Akbar from the ground. I watch this video

stitched from cellphone footage on a tablet held

between my father’s hands. They kill her. They run

her over. They burn her against a stone wall on a riverbank.

She was never burning a Quran, anyone could’ve seen that.

A year later, I recall the video and in order to find it,

the specificities blurred by now, I type into the search bar

Muslim woman red scarf burning Quran.

Only midway through the video do I realize

her face is so blood-drenched I have in my memory replaced it

with a red scarf. In fact, by the time the men get to burning her,

her body is so blood-drenched they must use their own scarves

to light her. But those halving miracles

derived from her marrow, exponentially

going extinct against the stone wall on the riverbank—

I couldn’t. I didn’t. When the men burned her,

the policemen said, Be careful of the fire.

.

by Hannah Perrin King

from Narrative Magazine

Laura Tanenbaum in Jacobin:

Laura Tanenbaum in Jacobin:

Rohit De and Surabhi Ranganathan in NYT:

Rohit De and Surabhi Ranganathan in NYT: One night in 1953, the Reverend Billy Graham awoke at two in the morning, went to his study, and started writing down ideas for the creation of a new religious journal. Graham, then in his mid-thirties, was an internationally renowned evangelist who held revival meetings that were attended by tens of thousands, in stadiums around the world. He had also become the leader of a cohort of pastors, theologians, and other Protestant luminaries who aspired to create a new Christian movement in the United States that avoided the cultural separatism of fundamentalism and the theological liberalism of mainline Protestantism. Harold Ockenga, a prominent minister and another key figure in the movement, called this more culturally engaged vision of conservative Christianity “new evangelicalism.” Graham believed a serious periodical could serve as the flagship for the movement. The idea for the publication, as he later wrote, was to “plant the Evangelical flag in the middle of the road, taking a conservative theological position but a definite liberal approach to social problems.” The magazine would be called Christianity Today.

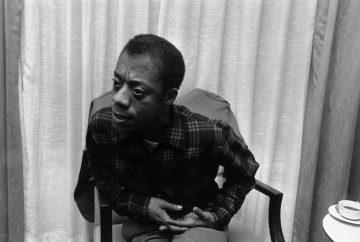

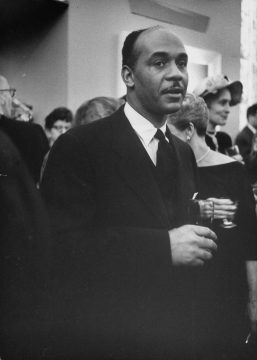

One night in 1953, the Reverend Billy Graham awoke at two in the morning, went to his study, and started writing down ideas for the creation of a new religious journal. Graham, then in his mid-thirties, was an internationally renowned evangelist who held revival meetings that were attended by tens of thousands, in stadiums around the world. He had also become the leader of a cohort of pastors, theologians, and other Protestant luminaries who aspired to create a new Christian movement in the United States that avoided the cultural separatism of fundamentalism and the theological liberalism of mainline Protestantism. Harold Ockenga, a prominent minister and another key figure in the movement, called this more culturally engaged vision of conservative Christianity “new evangelicalism.” Graham believed a serious periodical could serve as the flagship for the movement. The idea for the publication, as he later wrote, was to “plant the Evangelical flag in the middle of the road, taking a conservative theological position but a definite liberal approach to social problems.” The magazine would be called Christianity Today. “Complexity” was the term that Ralph Ellison deployed most often to describe black life and culture. And it is the term best suited to convey the character of this brilliant, often disapproving and unsparing man. Decades before Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and “Song of Solomon,” “Invisible Man” (1952) singularly defined the meaning of literary achievement. As a critic, Ellison was no less significant a thinker and stylist. Always, he was a philosopher of black expressive form and an astute cultural analyst.

“Complexity” was the term that Ralph Ellison deployed most often to describe black life and culture. And it is the term best suited to convey the character of this brilliant, often disapproving and unsparing man. Decades before Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and “Song of Solomon,” “Invisible Man” (1952) singularly defined the meaning of literary achievement. As a critic, Ellison was no less significant a thinker and stylist. Always, he was a philosopher of black expressive form and an astute cultural analyst. Dear imagined future self,

Dear imagined future self, False words, phony videos, doctored photos, and violent content are regular features on the online ecosystem worldwide. India is no exception, where such content, which often attracts millions of views, has led to

False words, phony videos, doctored photos, and violent content are regular features on the online ecosystem worldwide. India is no exception, where such content, which often attracts millions of views, has led to  Accusations of antisemitism

Accusations of antisemitism  I often think that my obsession with

I often think that my obsession with  Unlike Armstrong or Cukor, who stay true to Alcott’s timeline, Gerwig begins in the middle of the narrative, depicting the second half of the book while weaving in scenes drawn from the first. We open on the March sisters in their late teens or early twenties. The women in question are no longer very little, and the Civil War that cast a shadow over their youth has ended. We find the eldest, Meg, searching for contentment in her new life as the wife of a poor tutor (James Norton). Played by Emma Watson, she is the picture of grace if not always the voice, her Yankee accent at times on the brink. Tomboyish Jo—Ronan, offering a perfect compromise between Ryder’s timidity and Hepburn’s ham—is in New York avoiding an unwanted marriage proposal from her best friend, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), and chasing after her dream of becoming a writer. Amy (Florence Pugh), the bratty baby, is in Europe to hone her painting skills and find a society husband. Only sweet, sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen) remains at home, though she will soon depart on an adventure of a more permanent kind, as she learns to accept her slowly impending death, the consequence of childhood scarlet fever. As she says of her fate in one of Alcott’s most poetic lines, delivered with solemn elegance by Scanlen, who makes the most of Beth’s limited part: “It’s like the tide . . . when it turns, it goes slowly, but it can’t be stopped.”

Unlike Armstrong or Cukor, who stay true to Alcott’s timeline, Gerwig begins in the middle of the narrative, depicting the second half of the book while weaving in scenes drawn from the first. We open on the March sisters in their late teens or early twenties. The women in question are no longer very little, and the Civil War that cast a shadow over their youth has ended. We find the eldest, Meg, searching for contentment in her new life as the wife of a poor tutor (James Norton). Played by Emma Watson, she is the picture of grace if not always the voice, her Yankee accent at times on the brink. Tomboyish Jo—Ronan, offering a perfect compromise between Ryder’s timidity and Hepburn’s ham—is in New York avoiding an unwanted marriage proposal from her best friend, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), and chasing after her dream of becoming a writer. Amy (Florence Pugh), the bratty baby, is in Europe to hone her painting skills and find a society husband. Only sweet, sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen) remains at home, though she will soon depart on an adventure of a more permanent kind, as she learns to accept her slowly impending death, the consequence of childhood scarlet fever. As she says of her fate in one of Alcott’s most poetic lines, delivered with solemn elegance by Scanlen, who makes the most of Beth’s limited part: “It’s like the tide . . . when it turns, it goes slowly, but it can’t be stopped.” Jugaad is a hack, a hustle, a fix. It’s a lot from a little, the best with what you’ve got—which is likely not much, if you need jugaad. A “very DU word,” a Delhi University grad once explained to me, and I thought about how college students as a rule and around the world turn nothing into something (e.g., instant noodles).

Jugaad is a hack, a hustle, a fix. It’s a lot from a little, the best with what you’ve got—which is likely not much, if you need jugaad. A “very DU word,” a Delhi University grad once explained to me, and I thought about how college students as a rule and around the world turn nothing into something (e.g., instant noodles). A facility that saw 53,000 emergency room visits per year disappeared from Philadelphia this summer with the prolonged and still-unfinished closure of Hahnemann University Hospital. The 496-bed hospital employed 2,700 people and saw 17,000 admissions in 2017, its last year under the management of the Tenet Healthcare Corporation. Tenet, one of the nation’s largest for-profit hospital conglomerates, owned ninety-six hospitals and nearly 500 outpatient centers in the United States that year. Not all of them turned a profit. Hahnemann, for example, booked $790 million in revenue in 2017, $115 million short of breaking even. So Tenet embarked on an international restructuring program, liquidating seventeen low-margin hospitals in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Philadelphia, Tenet sold Hahnemann to Joel Freedman, a man from Los Angeles who sat on the advisory board of the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics (his name has since been removed from the center’s website) and managed an investment fund, Paladin Capital, with interests in “the world’s most innovative cyber companies,” according to its website. By spring 2019 Freedman was still losing $3 to $5 million a month on Hahnemann. He had burned through four CEOs in fifteen months. In June, hospital administrators announced that the facility was shutting down.

A facility that saw 53,000 emergency room visits per year disappeared from Philadelphia this summer with the prolonged and still-unfinished closure of Hahnemann University Hospital. The 496-bed hospital employed 2,700 people and saw 17,000 admissions in 2017, its last year under the management of the Tenet Healthcare Corporation. Tenet, one of the nation’s largest for-profit hospital conglomerates, owned ninety-six hospitals and nearly 500 outpatient centers in the United States that year. Not all of them turned a profit. Hahnemann, for example, booked $790 million in revenue in 2017, $115 million short of breaking even. So Tenet embarked on an international restructuring program, liquidating seventeen low-margin hospitals in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Philadelphia, Tenet sold Hahnemann to Joel Freedman, a man from Los Angeles who sat on the advisory board of the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics (his name has since been removed from the center’s website) and managed an investment fund, Paladin Capital, with interests in “the world’s most innovative cyber companies,” according to its website. By spring 2019 Freedman was still losing $3 to $5 million a month on Hahnemann. He had burned through four CEOs in fifteen months. In June, hospital administrators announced that the facility was shutting down. There is no escape from this dilemma – either all matter is conscious, or consciousness is something distinct from matter”: Alfred Russel Wallace put the point succinctly in 1870, and it is hard to see how his colleague

There is no escape from this dilemma – either all matter is conscious, or consciousness is something distinct from matter”: Alfred Russel Wallace put the point succinctly in 1870, and it is hard to see how his colleague  During the past eight years, many astute people, inside and outside the scientific community, have worried about the quality of scientific research. They warn of a “replication crisis.” In biomedicine and psychology in particular, it seems that a high proportion of published results cannot be reproduced. The absolute number of retractions for articles in these fields are rising. Whether or not it is right to talk of crisis, it is certainly reasonable to be concerned. What is going on?

During the past eight years, many astute people, inside and outside the scientific community, have worried about the quality of scientific research. They warn of a “replication crisis.” In biomedicine and psychology in particular, it seems that a high proportion of published results cannot be reproduced. The absolute number of retractions for articles in these fields are rising. Whether or not it is right to talk of crisis, it is certainly reasonable to be concerned. What is going on?

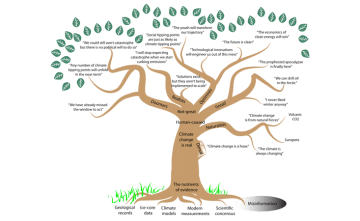

As a paleoclimatologist, I often find myself wondering why more people aren’t listening to the warnings, the data, the messages of climate woes—it’s not just a storm on the horizon, it’s here, knocking on the front door. In fact, it’s not even the front door anymore. You are on the roof, waiting for a helicopter to rescue you from your submerged house. The data is clear: The rates of current carbon dioxide release are 10 times greater than even the most rapid natural carbon catastrophe1 in the geological records, which brought about a miserable hothouse world of acidic oceans lacking oxygen, triggering a pulse of extinctions.2 Despite the evidence for anthropogenic climate change, views about the severity and impact of global warming diverge like branch points on a gnarly old oak tree (below).

As a paleoclimatologist, I often find myself wondering why more people aren’t listening to the warnings, the data, the messages of climate woes—it’s not just a storm on the horizon, it’s here, knocking on the front door. In fact, it’s not even the front door anymore. You are on the roof, waiting for a helicopter to rescue you from your submerged house. The data is clear: The rates of current carbon dioxide release are 10 times greater than even the most rapid natural carbon catastrophe1 in the geological records, which brought about a miserable hothouse world of acidic oceans lacking oxygen, triggering a pulse of extinctions.2 Despite the evidence for anthropogenic climate change, views about the severity and impact of global warming diverge like branch points on a gnarly old oak tree (below).