[Thanks to David Schneider.]

Category: Recommended Reading

Can The Deep South Learn from Germany’s Efforts to Confront Its Past?

Eric Banks at Bookforum:

Neiman’s book comprises two parts. The first is dedicated to the historical underpinnings of the German reckoning with Nazism and the Holocaust beginning in the early ’60s, with television broadcasts of the Eichmann and Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which led a younger generation to ask, for seemingly the first time, about the complacency and complicity of teachers, politicians, and above all fathers. (“Being German in my generation,” the author Carolin Emcke, born in 1967, tells Neiman, “means distrusting yourself.”) Learning from the Germans narrates the subsequent political and cultural evolution, including Willy Brandt’s 1970 Kniefall in penance to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Historians Debate of the 1980s, and the 2003–2005 construction of Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial, a site Neiman dislikes for the vagueness of its abstract form but whose gestation was admittedly long and difficult. Reunification posed a particular set of challenges to how Nazism and the Holocaust were publicly remembered; she contrasts the record of the former East Germany with that of West Germany and largely defends the avowed antifascist state from the charge that it failed to address the German past with anything comparable to Western efforts. Three decades after reunification, the extremist AfD party explicitly frames what it calls a “guilt cult” and threatens the success of the postwar project. Yet no other country (at least in Europe or North America) has made anything like the strides Germany has toward facing the legacy of national evils, whether colonialism in Britain and France or slavery and Jim Crow in America. Only in 2009 did the US Senate approve a resolution apologizing to black Americans for slavery.

Neiman’s book comprises two parts. The first is dedicated to the historical underpinnings of the German reckoning with Nazism and the Holocaust beginning in the early ’60s, with television broadcasts of the Eichmann and Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which led a younger generation to ask, for seemingly the first time, about the complacency and complicity of teachers, politicians, and above all fathers. (“Being German in my generation,” the author Carolin Emcke, born in 1967, tells Neiman, “means distrusting yourself.”) Learning from the Germans narrates the subsequent political and cultural evolution, including Willy Brandt’s 1970 Kniefall in penance to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Historians Debate of the 1980s, and the 2003–2005 construction of Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial, a site Neiman dislikes for the vagueness of its abstract form but whose gestation was admittedly long and difficult. Reunification posed a particular set of challenges to how Nazism and the Holocaust were publicly remembered; she contrasts the record of the former East Germany with that of West Germany and largely defends the avowed antifascist state from the charge that it failed to address the German past with anything comparable to Western efforts. Three decades after reunification, the extremist AfD party explicitly frames what it calls a “guilt cult” and threatens the success of the postwar project. Yet no other country (at least in Europe or North America) has made anything like the strides Germany has toward facing the legacy of national evils, whether colonialism in Britain and France or slavery and Jim Crow in America. Only in 2009 did the US Senate approve a resolution apologizing to black Americans for slavery.

more here.

The Horsewomen of the Belle Époque

Susanna Forrest at The Paris Review:

The glamour of both types of horsewoman was impeccable, their skill and bravery vertiginous. These long-dead performers became celebrities to me, fleshed out beyond the Impressionist postcards: Elvira Guerra, the first woman to compete against men at the Olympics in 1900; Caroline Loyo, “the diva of the crop” whose black eyes and disciplinaire riding brought the Jockey Club boys to the Paris circuses; and Suzanne Valadon, the acrobat of Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings who went on to be an artist herself after an injury cost her her career in the ring.

The glamour of both types of horsewoman was impeccable, their skill and bravery vertiginous. These long-dead performers became celebrities to me, fleshed out beyond the Impressionist postcards: Elvira Guerra, the first woman to compete against men at the Olympics in 1900; Caroline Loyo, “the diva of the crop” whose black eyes and disciplinaire riding brought the Jockey Club boys to the Paris circuses; and Suzanne Valadon, the acrobat of Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings who went on to be an artist herself after an injury cost her her career in the ring.

The modern circus was born in England in the late 1760s when a former soldier called Philip Astley pioneered the first recognizable circuses, centering on the horse. His wife, Patty Jones, became the first woman performer, standing on the backs of three horses as they cantered around the ring. Later she took to riding with her hands covered in bees.

more here.

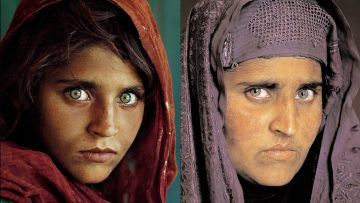

Shifting Perceptions of Muslim Women in The West

Sanam Maher at the TLS:

Much has been said about the burqa’s ability to conceal. In 2006, speaking to Reuters, the then Prime Minister of Italy Romano Prodi insisted, “You must be seen. This is common sense, I think. It is important for our society”. In Britain that same year, Muslims accounted for only 3 per cent of the population, and the number of burqa wearers was a fraction of that. When Jack Straw, as leader of the House of Commons, wrote, in a column for the Lancashire Telegraph, that he asked Muslim women to take off their coverings in meetings because “so many of the judgments we all make about other people come from seeing their faces”, the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, chimed in with support. “It is a mark of separation”, and it makes non-Muslims “feel uncomfortable”. The Shadow Home Secretary David Davis went further: by insisting on such practices, Muslims were enacting “voluntary apartheid”. In 2011 France became the first European country to make it illegal to wear a face-covering veil in public. The country is home to an estimated 5 million Muslims (the largest Muslim population in western Europe), and it has long been suggested that reactions to the veil mask deeper concerns about the growing minority.

The veil, face-covering or otherwise, has become a central component in the Western understanding of Muslim women – and, indeed, men.

more here.

Staring at Hell: The aesthetics of architecture in a ruined world

Kate Wagner in The Baffler:

WHEN I WAS an eleven-year-old child struggling with nascent mental illness, I received some perhaps ill-considered advice from one of many therapists: “Knowledge is power.” The idea was that by learning more about the things I feared, I would become less scared about them. In some ways, this worked. Researching the murder rate for our small town (zero murders) and the statistics of prepubescent heart attacks (extraordinarily rare) quelled some of my more ungrounded fears. This prescription for knowledge, however, was contraindicated by an existing condition of mine: morbid fascination. Why someone with clinical anxiety would spend a great deal of their time reading about the abject man-made horrors of the world—from industrial accidents to engineering catastrophes, from transportation accidents to public health crises—is a question I have asked myself for years. While perhaps less popular than horror movies and true-crime podcasts, the spectacle of catastrophe is nonetheless fascinating to the millions of people who spend their evenings binging Seconds from Disaster or Chernobyl.

WHEN I WAS an eleven-year-old child struggling with nascent mental illness, I received some perhaps ill-considered advice from one of many therapists: “Knowledge is power.” The idea was that by learning more about the things I feared, I would become less scared about them. In some ways, this worked. Researching the murder rate for our small town (zero murders) and the statistics of prepubescent heart attacks (extraordinarily rare) quelled some of my more ungrounded fears. This prescription for knowledge, however, was contraindicated by an existing condition of mine: morbid fascination. Why someone with clinical anxiety would spend a great deal of their time reading about the abject man-made horrors of the world—from industrial accidents to engineering catastrophes, from transportation accidents to public health crises—is a question I have asked myself for years. While perhaps less popular than horror movies and true-crime podcasts, the spectacle of catastrophe is nonetheless fascinating to the millions of people who spend their evenings binging Seconds from Disaster or Chernobyl.

A special subset of disaster porn is what we might call infrastructural tragedy: bridge collapses, oil spills, toxic waste dumps, nuclear meltdowns, industrial accidents of all stripes, and, on a slower timescale, the left-behind, dystopian landscapes of post-industrial decay and blight. From William Blake’s “dark Satanic Mills” to Koyaanisqatsi, from the photography of Margaret Bourke-White, Richard Misrach, and David T. Hanson to Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier’s fascination with grain elevators, the impact on the arts made by the horrors of production and the landscapes they’ve left behind—arguably necessary evils that make our contemporary way of life possible—spans disciplines and centuries.

More here.

“Advocate” Documents the Battles of an Israeli Activist

Naomi Fry in The New Yorker:

The thought-provoking Israeli documentary “Advocate,” from the directors Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaïche, opens with its subject, the human-rights lawyer Lea Tsemel, making her way resolutely toward the elevators at the district court in Tel Aviv. A short and solidly built woman in her seventies, with a mop of dark hair and kohl-rimmed eyes, Tsemel is on her way to the courthouse’s detention cells to meet with a client. “Is it going down?” she asks as she approaches the elevator’s nearly closed doors, before sticking her leg between them and muscling her way in. “Lea, what will become of you? When will you mend your ways?” a man inside the elevator asks her. “Who, me? I’m a lost cause,” she answers.

The thought-provoking Israeli documentary “Advocate,” from the directors Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaïche, opens with its subject, the human-rights lawyer Lea Tsemel, making her way resolutely toward the elevators at the district court in Tel Aviv. A short and solidly built woman in her seventies, with a mop of dark hair and kohl-rimmed eyes, Tsemel is on her way to the courthouse’s detention cells to meet with a client. “Is it going down?” she asks as she approaches the elevator’s nearly closed doors, before sticking her leg between them and muscling her way in. “Lea, what will become of you? When will you mend your ways?” a man inside the elevator asks her. “Who, me? I’m a lost cause,” she answers.

The exchange is joshing, but Tsemel, an Israeli Jew who has been practicing human-rights law since 1972, is a controversial figure in her country—one whose determination to thrust a tenacious leg forward and crack open the doors of the uniform Zionist narrative has often been met with her compatriots’ deep anger. In her first trial, she defended members of the Arab-Jewish cell Red Front. Their leader, Udi Adiv, a politically radicalized former I.D.F. paratrooper, was charged with treason for delivering classified information to Syria. (Adiv claimed that he was attempting to work toward the liberation of the Palestinian people.) Over the past four-and-a-half decades, Tsemel has focussed her practice on defending Palestinians who, as she explains in a TV interview from the nineties that is included in the documentary, “you call terrorists, but that the average person in the world would call freedom fighters.”

More here.

Thursday, January 9, 2020

Omnicide: Who is responsible for the gravest of all crimes?

Danielle Celermajer at the ABC (Australia):

As the full extent of the devastation of the Holocaust became apparent, a Polish Jew whose entire family had been killed, Raphael Lemkin, came to realise that there was no word for the distinctive crime that had been committed: the murder of a people. His life work became finding a word to name the crime and then convincing the world to use it and condemn it: genocide. Today, not only has genocide become a dreadful part of our lexicon. We recognise it as perhaps the gravest of all crimes.

As the full extent of the devastation of the Holocaust became apparent, a Polish Jew whose entire family had been killed, Raphael Lemkin, came to realise that there was no word for the distinctive crime that had been committed: the murder of a people. His life work became finding a word to name the crime and then convincing the world to use it and condemn it: genocide. Today, not only has genocide become a dreadful part of our lexicon. We recognise it as perhaps the gravest of all crimes.

During these first days of the third decade of the twenty-first century, as we watch humans, animals, trees, insects, fungi, ecosystems, forests, rivers (and on and on) being killed, we find ourselves without a word to name what is happening. True, in recent years, environmentalists have coined the term ecocide, the killing of ecosystems — but this is something more. This is the killing of everything. Omnicide.

Some will object, no doubt, that this does not count as a “cide” — a murder or killing — but is rather a natural phenomenon, albeit an unspeakably regrettable one. Where is the murderous intent? Difficult to locate, admittedly, but a new crime also requires a new understanding of culpability.

More here.

Fighter pilot turned author Mohammed Hanif on mining his homeland of Pakistan for humour

Fionnuala McHugh in the South China Morning Post:

On a Sunday night, exactly 22 weeks after the protests against an extradition bill had begun on June 9, prize-winning Pakistani journalist and novelist Mohammed Hanif checked into his room at Robert Black College, on the University of Hong Kong campus. Until then, the city’s social unrest had usually been confined to weekends; but, two days earlier, Chow Tsz-lok, a student from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, had died in unexplained circumstances while police were dispersing a crowd with tear gas. The Monday morning after Hanif’s arrival, a traffic policeman shot a protester at 7.20am during disturbances in Sai Wan Ho. Matters escalated.

On a Sunday night, exactly 22 weeks after the protests against an extradition bill had begun on June 9, prize-winning Pakistani journalist and novelist Mohammed Hanif checked into his room at Robert Black College, on the University of Hong Kong campus. Until then, the city’s social unrest had usually been confined to weekends; but, two days earlier, Chow Tsz-lok, a student from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, had died in unexplained circumstances while police were dispersing a crowd with tear gas. The Monday morning after Hanif’s arrival, a traffic policeman shot a protester at 7.20am during disturbances in Sai Wan Ho. Matters escalated.

Hanif, who lives in Karachi, had been invited last year to give the 2019 PEN Hong Kong Literature & Human Rights lecture at HKU. PEN, which stood for Poets, Essayists, Novelists but now embraces all literary forms in its role as human-rights watchdog, planned for Hanif to take part in an evening with local writers titled “We Still Laugh: Humour as a Literary Relief Valve”. By lunchtime on his first day in Hong Kong, however, student outrage had been ignited, tear gas was seeping through Central and no one was laughing.

More here.

Lessons from Australia’s Bushfires: We Need More Science, Less Rhetoric

Claire Lehmann in Quillette:

In 2019, short-term weather fluctuations in the Indian Ocean—the Indian Ocean Dipole, as scientists call it—pushed moist ocean air away from Australia’s shores, causing a severe drought, and drying out the leaves, sticks and soil on the bush floor.

In 2019, short-term weather fluctuations in the Indian Ocean—the Indian Ocean Dipole, as scientists call it—pushed moist ocean air away from Australia’s shores, causing a severe drought, and drying out the leaves, sticks and soil on the bush floor.

This has come in tandem with unusually strong and sustained winds associated with a separate phenomenon known as the Antarctic Oscillation, which have pushed fires in all directions, turning isolated local crises into regional disasters. And of course all of this comes amid a steady increase in average temperatures across Australia, a phenomenon that climate scientists have warned us about for decades. They also have correctly predicted that long-term climate-change trends will increasingly interact disastrously with short-term climate phenomena in a way that catalyses and exacerbates extreme weather events.

Unfortunately, successive Australian governments have failed to adequately heed these warnings. A more aggressive use of controlled burns might have given firefighters a chance to control this season’s bushfires. But, as has been the case in other nations, climate policy in Australia has been mired in partisan politics, with both sides using the issue to score points instead of implementing sensible and pragmatic policies.

More here.

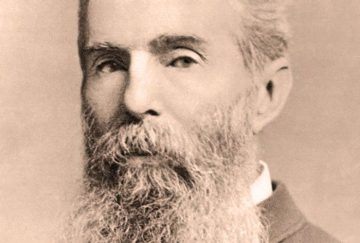

Herman Melville the Poet

Gillian Osborne in the Boston Review:

The Library of America edition of Herman Melville’s Complete Poems collects, for the first time, all of Melville’s known poetry. This includes collections published during his lifetime and reviewed widely, such as Battle-Pieces (1866), completed in the aftermath of the Civil War. In addition, the book collects work largely unknown by—and unavailable to—general readers until now. This latter category includes the epic poem Clarel (1876), notable both for being the longest American poem to date, and for having most of its first edition burned by the publisher to clear out warehouse space. Library of America is billing the Complete Poems as a resuscitation of one of the United States’ greatest nineteenth-century poets, establishing Melville within the company of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. But while the collection has the potential to change popular understanding of the kind of writer Melville was, the pleasures of reading Melville as a poet are ambiguous, as is the urge to classify him as great.

The Library of America edition of Herman Melville’s Complete Poems collects, for the first time, all of Melville’s known poetry. This includes collections published during his lifetime and reviewed widely, such as Battle-Pieces (1866), completed in the aftermath of the Civil War. In addition, the book collects work largely unknown by—and unavailable to—general readers until now. This latter category includes the epic poem Clarel (1876), notable both for being the longest American poem to date, and for having most of its first edition burned by the publisher to clear out warehouse space. Library of America is billing the Complete Poems as a resuscitation of one of the United States’ greatest nineteenth-century poets, establishing Melville within the company of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. But while the collection has the potential to change popular understanding of the kind of writer Melville was, the pleasures of reading Melville as a poet are ambiguous, as is the urge to classify him as great.

More here.

Dave Chappelle on the Art of Stand-up Comedy

Thursday Poem

.

You think you are alive

because you breathe air?

Shame on you,

that you are alive in such a limited way.

Don’t be without Love,

so you won’t feel dead.

Die in Love

and stay alive forever.

How Inequality Imperils Cooperation

Brian Gallagher in Nautilus:

Last year news came that Indian billionaire Gautam Adani was set to exploit Australian coal reserves. The deal, The New York Times reported, was the result of a successful campaign by the Adani Group, a vast conglomerate with diverse interests, to capture the hearts and minds of Queenslanders, who occupy Australia’s second-largest state. It’s a project that will, in the short term, help power development in India and Bangladesh, where renewable sources of energy can be too costly to implement. India, unlike the United States and Western Europe, “doesn’t have a choice” about whether to use coal, Adani told the Times. In the long run, relying on coal will exacerbate efforts to stem global heating, as burning coal is one of the main drivers of climate change. One billionaire’s endeavor, in other words, represents a social dilemma of global proportions. India’s reliance on coal threatens to destroy public goods—clean air, favorable weather patterns, national security—and upend cooperation efforts to develop and implement renewable energy.

Christian Hilbe, a mathematician, directs a group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology, in Germany, where he studies the conditions under which people cooperate. His group builds predictive models inspired by social dilemmas like climate change, which involve cooperation dynamics too complex to model realistically. “We want to distill the essence or the logic of this problem, make it as simple as possible, and then understand this very simple model,” Hilbe told me in a recent interview. “We are all aware that by solving the simple model, we don’t solve the climate change problem. But still we want to understand some of the strategic calibrations taking place in the whole game.” I caught up with Hilbe shortly after he published results of his explorations in the journal Nature. In his paper, “Social dilemmas among unequals,” Hilbe—along with his co-authors from the University of Exeter Business School, the Institute for Science and Technology Austria, and Harvard—found that, among other things, extreme inequality prevents players from cooperating to provision resources for public goods. “Our findings,” the researchers concluded, “have implications for policy-makers concerned with equity, efficiency and the provisioning of public goods.” In our conversation, Hilbe broke down the thinking behind his model and the consequences of his results.

More here.

UK Group Tackles Reproducibility in Research

Emily Makowski in The Scientist:

In 2016, a Nature survey of 1,576 researchers revealed that more than 70 percent of them had tried and failed to reproduce another scientist’s experiments—and more than half failed to replicate their own. These and other recent findings on the lack of reproducibility in scientific research have inspired the creation of groups such as the UK Reproducibility Network (UKRN). Launched in March 2019, the UKRN is an interdisciplinary consortium that aims to tackle this issue in order to bolster research quality. Last month, 10 UK universities became part of the UKRN, joining a network that already includes stakeholders such as the Academy of Medical Sciences, Research Libraries UK, the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, journals including Nature and PLOS, and local networks of researchers, reports Times Higher Education. The Scientist spoke with Marcus Munafò, a biological psychologist at the University of Bristol and the chair of the UKRN’s steering group of researchers, about UKRN’s structure, activities, and future plans.

In 2016, a Nature survey of 1,576 researchers revealed that more than 70 percent of them had tried and failed to reproduce another scientist’s experiments—and more than half failed to replicate their own. These and other recent findings on the lack of reproducibility in scientific research have inspired the creation of groups such as the UK Reproducibility Network (UKRN). Launched in March 2019, the UKRN is an interdisciplinary consortium that aims to tackle this issue in order to bolster research quality. Last month, 10 UK universities became part of the UKRN, joining a network that already includes stakeholders such as the Academy of Medical Sciences, Research Libraries UK, the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, journals including Nature and PLOS, and local networks of researchers, reports Times Higher Education. The Scientist spoke with Marcus Munafò, a biological psychologist at the University of Bristol and the chair of the UKRN’s steering group of researchers, about UKRN’s structure, activities, and future plans.

TS: There’s been a lot of talk about the reproducibility crisis over the past few years. Could you give our readers some background about what led to the creation of UKRN?

Marcus Munafò: I’m not sure I particularly like the crisis narrative. There’s been a lot of interest in whether or not the research that [people] do is as robust and replicable as it could be, and it’s healthy to reflect on whether or not we could do better. I think any enterprise should have some proportion of its effort invested in thinking about whether or not it can improve the way in which it works. So it’s much better to think of this in terms of that kind of framing.

More here.

Wednesday, January 8, 2020

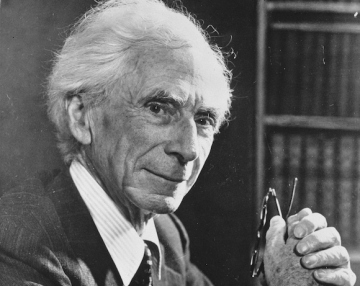

What people get wrong about Bertrand Russell

Julian Baggini in Prospect:

In philosophical circles, there are two Bertrand Russells, only one of whom died 50 years ago. The first is the short-lived genius philosopher of 1897-1913, whose groundbreaking work on logic shaped the analytic tradition which dominated Anglo-American philosophy during the 20th century. The second is the longer-lived public intellectual and campaigner of 1914-1970, known to a wider audience for his popular books such as Why I Am Not a Christian, Marriage and Morals and A History of Western Philosophy.

In philosophical circles, there are two Bertrand Russells, only one of whom died 50 years ago. The first is the short-lived genius philosopher of 1897-1913, whose groundbreaking work on logic shaped the analytic tradition which dominated Anglo-American philosophy during the 20th century. The second is the longer-lived public intellectual and campaigner of 1914-1970, known to a wider audience for his popular books such as Why I Am Not a Christian, Marriage and Morals and A History of Western Philosophy.

The public may have preferred the second Russell but many philosophers see this iteration as a sell-out who betrayed the first. This view is best reflected in Ray Monk’s exhaustive biography. The first volume, which went up to 1921, was almost universally acclaimed, but some (unfairly) condemned the second as a hatchet-job. It was as though Monk had become exasperated by his subject.

Monk admired the logician Russell who “supports his views with rigorous and sophisticated arguments, and deals with objections carefully and respectfully.” But he despaired that in the popular political writings that dominated the second half of Russell’s life, “these qualities are absent, replaced with empty rhetoric, blind dogmatism and a cavalier refusal to take the views of his opponents seriously.” In Monk’s view, Russell “abandoned a subject of which he was one of the greatest practitioners since Aristotle in favour of one to which he had very little of any value to contribute.”

Monk’s assessment has become orthodoxy among professional philosophers. But…

More here.

Lab-grown food will soon destroy farming – and save the planet

George Monbiot in The Guardian:

It sounds like a miracle, but no great technological leaps were required. In a commercial lab on the outskirts of Helsinki, I watched scientists turn water into food. Through a porthole in a metal tank, I could see a yellow froth churning. It’s a primordial soup of bacteria, taken from the soil and multiplied in the laboratory, using hydrogen extracted from water as its energy source. When the froth was siphoned through a tangle of pipes and squirted on to heated rollers, it turned into a rich yellow flour.

It sounds like a miracle, but no great technological leaps were required. In a commercial lab on the outskirts of Helsinki, I watched scientists turn water into food. Through a porthole in a metal tank, I could see a yellow froth churning. It’s a primordial soup of bacteria, taken from the soil and multiplied in the laboratory, using hydrogen extracted from water as its energy source. When the froth was siphoned through a tangle of pipes and squirted on to heated rollers, it turned into a rich yellow flour.

This flour is not yet licensed for sale. But the scientists, working for a company called Solar Foods, were allowed to give me some while filming our documentary Apocalypse Cow. I asked them to make me a pancake: I would be the first person on Earth, beyond the lab staff, to eat such a thing. They set up a frying pan in the lab, mixed the flour with oat milk, and I took my small step for man. It tasted … just like a pancake.

But pancakes are not the intended product. Such flours are likely soon to become the feedstock for almost everything. In their raw state, they can replace the fillers now used in thousands of food products. When the bacteria are modified they will create the specific proteins needed for lab-grown meat, milk and eggs.

More here.

How To Avoid Swallowing War Propaganda

Nathan J. Robinson in Current Affairs:

What happens in the leadup to war is that government officials make claims about the enemy, and then those claims appear in newspapers (“U.S. officials say Saddam poses an imminent threat”) and then in the public consciousness, the “U.S. officials say” part disappears, so that the claim is taken for reality without ever really being scrutinized. This happens because newspapers are incredibly irresponsible and believe that so long as you attach “Experts say” or “President says” to a claim, you are off the hook when people end up believing it, because all you did was relay the fact that a person said a thing, you didn’t say it was true. This is the approach the New York Times took to Bush administration allegations in the leadup to the Iraq War, and it meant that false claims could become headline news just because a high-ranking U.S. official said them. [UPDATE: here’s an example from Vox, today, of a questionable government claim being magically transformed into a certain fact.]

What happens in the leadup to war is that government officials make claims about the enemy, and then those claims appear in newspapers (“U.S. officials say Saddam poses an imminent threat”) and then in the public consciousness, the “U.S. officials say” part disappears, so that the claim is taken for reality without ever really being scrutinized. This happens because newspapers are incredibly irresponsible and believe that so long as you attach “Experts say” or “President says” to a claim, you are off the hook when people end up believing it, because all you did was relay the fact that a person said a thing, you didn’t say it was true. This is the approach the New York Times took to Bush administration allegations in the leadup to the Iraq War, and it meant that false claims could become headline news just because a high-ranking U.S. official said them. [UPDATE: here’s an example from Vox, today, of a questionable government claim being magically transformed into a certain fact.]

More here.

Risa Wechsler: The Search for Dark Matter and What We’ve Found So Far

Crystal Eastman’s Revolution

Vivian Gornick at The Nation:

Greenwich Village, in the early years of the 20th century, was a working-class neighborhood that had let the bohemians in. Eastman was enchanted. Describing the crowded street scene in a letter to her mother, she wrote, “Everyone is out. Mothers and fathers and babies line the doorsteps…little girls playing…in the middle of the street, and boys running in and out, chasing each other.” And to Max, urging him to join her when he graduated from college, she wrote, “I love it so for the people that are there and the thousands of things they do and think about.” The women and men she especially loved were “all the interesting between ones who really know how to live—who are working hard at something all the time; and especially the radicals, the reformers, the students—because they are open-minded, and eager over every new movement, and because they know when it is right for them to let go and amuse themselves and because they can laugh, even at themselves.” (Pace Emma Goldman: If I can’t dance, I’m not coming to your revolution.)

Greenwich Village, in the early years of the 20th century, was a working-class neighborhood that had let the bohemians in. Eastman was enchanted. Describing the crowded street scene in a letter to her mother, she wrote, “Everyone is out. Mothers and fathers and babies line the doorsteps…little girls playing…in the middle of the street, and boys running in and out, chasing each other.” And to Max, urging him to join her when he graduated from college, she wrote, “I love it so for the people that are there and the thousands of things they do and think about.” The women and men she especially loved were “all the interesting between ones who really know how to live—who are working hard at something all the time; and especially the radicals, the reformers, the students—because they are open-minded, and eager over every new movement, and because they know when it is right for them to let go and amuse themselves and because they can laugh, even at themselves.” (Pace Emma Goldman: If I can’t dance, I’m not coming to your revolution.)

Eastman was bent on living a life of meaning that would include, as she liked to say, loving hard as well as working hard. (Rosa Luxemburg said almost the identical thing when she urged socialists to make the revolution, yes, but not give up the joy of life.)

more here.

Mahmoud Darwish and The Spectre of The Arab Intellectual-Prophet

Zeina G. Halabi at Eurozine:

This dialectical reconstruction of exile is one of the most revealing portraits of Darwish. Invoking his poetry’s prophetic iconography, it evokes displacement, absence, and the privilege of representation, about who speaks for the wandering people and how. It asks the question of how exile is framed temporally, probing the conceptions of time at work in this experience. Palestine is thus revealed across three successive temporalities: historically embedded in Biblical tradition and collective memory; a signifier in the present of displacement and loss; and projected into the future by the spectral figure of the exiled poet-prophet. The scene is thus about the intertwinement of the lyrical and the political, the personal and the collective, and the spectral and messianic; all set the parameters of the intellectual-prophet.

This dialectical reconstruction of exile is one of the most revealing portraits of Darwish. Invoking his poetry’s prophetic iconography, it evokes displacement, absence, and the privilege of representation, about who speaks for the wandering people and how. It asks the question of how exile is framed temporally, probing the conceptions of time at work in this experience. Palestine is thus revealed across three successive temporalities: historically embedded in Biblical tradition and collective memory; a signifier in the present of displacement and loss; and projected into the future by the spectral figure of the exiled poet-prophet. The scene is thus about the intertwinement of the lyrical and the political, the personal and the collective, and the spectral and messianic; all set the parameters of the intellectual-prophet.

This is where the enmeshment of the poet-prophet, Palestine, and manifold temporalities turn into a metanarrative. We watch Bitton representing Darwish; he represents the Palestinians in 1997 from the vantage point of today’s coups, revolutions, and civil wars, all of which have had an effect on the conception of the ‘prophetic intellectual’.

more here.