Yasmeen Serhan in The Atlantic:

Violence has become a familiar feature of many of the places convulsed by protests around the world—especially when the government gets involved. Such is the case in France, where clashes with police have resulted in numerous injuries. In Iraq and Chile, they have even led to deaths. The unrest emerging in India, however, is of a different breed. There, the sectarian violence that has resulted in dozens of deaths in the capital city of Delhi follows months of peaceful protests against a new citizenship law. In this case, it wasn’t a government crackdown that spurred the deaths, but rather, the government’s seeming unwillingness to quell the rampage in the first place.

Violence has become a familiar feature of many of the places convulsed by protests around the world—especially when the government gets involved. Such is the case in France, where clashes with police have resulted in numerous injuries. In Iraq and Chile, they have even led to deaths. The unrest emerging in India, however, is of a different breed. There, the sectarian violence that has resulted in dozens of deaths in the capital city of Delhi follows months of peaceful protests against a new citizenship law. In this case, it wasn’t a government crackdown that spurred the deaths, but rather, the government’s seeming unwillingness to quell the rampage in the first place.

The scale of the violence in Delhi, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s muted reaction to it, raises questions about the obligation of governments to stem violence. Is it enough to call for calm, as Modi has done, or is a more robust response required? Is failing to stamp out turmoil any different from being the cause of it in the first place? Compared with some mass demonstrations around the world, Delhi’s have been relatively peaceful. Galvanized by the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which excludes Muslims from the list of religious groups in neighboring countries eligible for Indian citizenship, nationwide protests have largely centered on the law’s constitutionality and what it means for India’s identity. Critics argue that the law implicitly makes religion a criterion for nationality, thereby threatening the country’s status as a secular and pluralist democracy. In Delhi, this opposition has manifested in sit-ins, candlelight vigils, and public readings of the preamble to the Indian constitution.

More here.

You watch John Mulaney in his new Netflix special, Kid Gorgeous at Radio City, and it’s hard not to think he was made in some lab to do stand-up. I like to describe him as the LeBron James of comedy, in that he is great at everything a stand-up can be good at. But it wasn’t always that way. Once upon a time, Mulaney was a clever young man, bombing specifically for audiences who paid to see him. Everything changed after the worst set of his life, one fateful night in New Jersey. It’s the story of how he got his joke about $100 million movies to work.

You watch John Mulaney in his new Netflix special, Kid Gorgeous at Radio City, and it’s hard not to think he was made in some lab to do stand-up. I like to describe him as the LeBron James of comedy, in that he is great at everything a stand-up can be good at. But it wasn’t always that way. Once upon a time, Mulaney was a clever young man, bombing specifically for audiences who paid to see him. Everything changed after the worst set of his life, one fateful night in New Jersey. It’s the story of how he got his joke about $100 million movies to work. Anyone who has read histories of the Cold War, including the

Anyone who has read histories of the Cold War, including the  In August 1958, gangs of white youths began systematically attacking West Indians in London’s Notting Hill, assaulting them with iron bars and meat cleavers and milk bottles.

In August 1958, gangs of white youths began systematically attacking West Indians in London’s Notting Hill, assaulting them with iron bars and meat cleavers and milk bottles.  THE ROMANIAN DIRECTOR Corneliu Porumboiu may be the most epistemologically preoccupied filmmaker this side of Errol Morris, but, having spent his first fourteen years living under the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Père Ubu–ist regime, his sense of the absurd is second nature.

THE ROMANIAN DIRECTOR Corneliu Porumboiu may be the most epistemologically preoccupied filmmaker this side of Errol Morris, but, having spent his first fourteen years living under the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Père Ubu–ist regime, his sense of the absurd is second nature. A truly literary history eludes most working historians. Their books are too often weighed down by specialist jargon, and they know that neglecting scholarly trappings—extensive footnotes, name-checking fellow historians—means risking professional irrelevance. It is nearly impossible to reach that most coveted literary destination: a serious argument delivered with a light touch.

A truly literary history eludes most working historians. Their books are too often weighed down by specialist jargon, and they know that neglecting scholarly trappings—extensive footnotes, name-checking fellow historians—means risking professional irrelevance. It is nearly impossible to reach that most coveted literary destination: a serious argument delivered with a light touch. A YEAR BEFORE ANNA KAVAN WAS FOUND DEAD

A YEAR BEFORE ANNA KAVAN WAS FOUND DEAD There are many arguments for theism, most of them not worth rehearsing. The ontological argument, first formulated by St Anselm in the 11th century and reframed by the 17th-century French rationalist René Descartes (1596-1650), maintains that God must exist because humans have an idea of a perfect being and existence is necessary to perfection. Since many of us have no such idea, it is a feeble gambit. The arguments of creationists are feebler, since they involve concocting a theory of intelligent design to fill gaps in science that the growth of knowledge may one day close. The idea of God is not a pseudo-scientific speculation.

There are many arguments for theism, most of them not worth rehearsing. The ontological argument, first formulated by St Anselm in the 11th century and reframed by the 17th-century French rationalist René Descartes (1596-1650), maintains that God must exist because humans have an idea of a perfect being and existence is necessary to perfection. Since many of us have no such idea, it is a feeble gambit. The arguments of creationists are feebler, since they involve concocting a theory of intelligent design to fill gaps in science that the growth of knowledge may one day close. The idea of God is not a pseudo-scientific speculation. Are humans the only animals that caucus? As the early 2020 presidential election season suggests, there are probably more natural and efficient ways to make a group choice. But we’re certainly not the only animals on Earth that vote. We’re not even the only primates that primary. Any animal living in a group needs to make decisions as a group, too. Even when they don’t agree with their companions, animals rely on one another for protection or help finding food. So they have to find ways to reach consensus about what the group should do next, or where it should live. While they may not conduct continent-spanning electoral contests like this coming Super Tuesday, species ranging from primates all the way to insects have methods for finding agreement that are surprisingly democratic. As meerkats start each day, they emerge from their burrows into the sunlight, then begin searching for food. Each meerkat forages for itself, digging in the dirt for bugs and other morsels, but they travel in loose groups, each animal up to about 30 feet from its neighbors, says Marta Manser, an animal-behavior scientist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. Nonetheless, the meerkats move as one unit, drifting across the desert while they search and munch.

Are humans the only animals that caucus? As the early 2020 presidential election season suggests, there are probably more natural and efficient ways to make a group choice. But we’re certainly not the only animals on Earth that vote. We’re not even the only primates that primary. Any animal living in a group needs to make decisions as a group, too. Even when they don’t agree with their companions, animals rely on one another for protection or help finding food. So they have to find ways to reach consensus about what the group should do next, or where it should live. While they may not conduct continent-spanning electoral contests like this coming Super Tuesday, species ranging from primates all the way to insects have methods for finding agreement that are surprisingly democratic. As meerkats start each day, they emerge from their burrows into the sunlight, then begin searching for food. Each meerkat forages for itself, digging in the dirt for bugs and other morsels, but they travel in loose groups, each animal up to about 30 feet from its neighbors, says Marta Manser, an animal-behavior scientist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. Nonetheless, the meerkats move as one unit, drifting across the desert while they search and munch. Greta’s father, Svante, and I are what is known in Sweden as “cultural workers” – trained in opera, music and theatre with half a career of work in those fields behind us. When I was pregnant with Greta, and working in Germany, Svante was acting at three different theatres in Sweden simultaneously. I had several years of binding contracts ahead of me at various opera houses all over Europe. With 1,000km between us, we talked over the phone about how we could get our new reality to work.

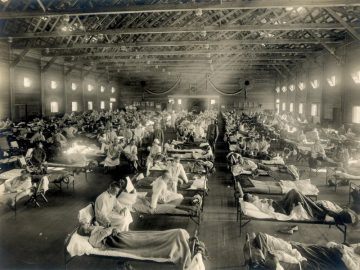

Greta’s father, Svante, and I are what is known in Sweden as “cultural workers” – trained in opera, music and theatre with half a career of work in those fields behind us. When I was pregnant with Greta, and working in Germany, Svante was acting at three different theatres in Sweden simultaneously. I had several years of binding contracts ahead of me at various opera houses all over Europe. With 1,000km between us, we talked over the phone about how we could get our new reality to work. Haskell County, Kansas, lies in the southwest corner of the state, near Oklahoma and Colorado. In 1918 sod houses were still common, barely distinguishable from the treeless, dry prairie they were dug out of. It had been cattle country—a now bankrupt ranch once handled 30,000 head—but Haskell farmers also raised hogs, which is one possible clue to the origin of the crisis that would terrorize the world that year. Another clue is that the county sits on a major migratory flyway for 17 bird species, including sand hill cranes and mallards. Scientists today understand that bird influenza viruses, like human influenza viruses, can also infect hogs, and when a bird virus and a human virus infect the same pig cell, their different genes can be shuffled and exchanged like playing cards, resulting in a new, perhaps especially lethal, virus.

Haskell County, Kansas, lies in the southwest corner of the state, near Oklahoma and Colorado. In 1918 sod houses were still common, barely distinguishable from the treeless, dry prairie they were dug out of. It had been cattle country—a now bankrupt ranch once handled 30,000 head—but Haskell farmers also raised hogs, which is one possible clue to the origin of the crisis that would terrorize the world that year. Another clue is that the county sits on a major migratory flyway for 17 bird species, including sand hill cranes and mallards. Scientists today understand that bird influenza viruses, like human influenza viruses, can also infect hogs, and when a bird virus and a human virus infect the same pig cell, their different genes can be shuffled and exchanged like playing cards, resulting in a new, perhaps especially lethal, virus. For John Morgan, an American expat living in Budapest, controlling the form the world takes comes down to shaping how white people dream.

For John Morgan, an American expat living in Budapest, controlling the form the world takes comes down to shaping how white people dream.

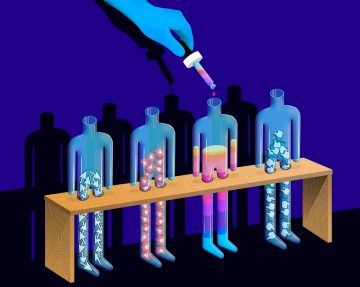

Dr. John Haygarth knew that there was something suspicious about Perkins’s Metallic Tractors. He’d heard all the theories about the newly patented medical device—about the way flesh reacted to metal, about noxious electrical fluids being expelled from the body. He’d heard that people plagued by rheumatism, pleurisy, and toothache swore the instrument offered them miraculous relief. Even George Washington was said to own a set. But Haygarth, a physician who had pioneered a method of preventing smallpox, sensed a sham. He set out to find the evidence. The year was 1799, and the Perkins tractors were already an international phenomenon. The device consisted of a pair of metallic rods—rounded on one end and tapering, at the other, to a point. Its inventor, Elisha Perkins, insisted that gently stroking each tractor over the affected area in alternation would draw off the electricity and provide relief. Thousands of sets were sold, for twenty-five dollars each. People were even said to have auctioned off their horses just to get hold of a pair. And, in an era when your alternatives might be bloodletting, leeches, and purging, you could see the appeal.

Dr. John Haygarth knew that there was something suspicious about Perkins’s Metallic Tractors. He’d heard all the theories about the newly patented medical device—about the way flesh reacted to metal, about noxious electrical fluids being expelled from the body. He’d heard that people plagued by rheumatism, pleurisy, and toothache swore the instrument offered them miraculous relief. Even George Washington was said to own a set. But Haygarth, a physician who had pioneered a method of preventing smallpox, sensed a sham. He set out to find the evidence. The year was 1799, and the Perkins tractors were already an international phenomenon. The device consisted of a pair of metallic rods—rounded on one end and tapering, at the other, to a point. Its inventor, Elisha Perkins, insisted that gently stroking each tractor over the affected area in alternation would draw off the electricity and provide relief. Thousands of sets were sold, for twenty-five dollars each. People were even said to have auctioned off their horses just to get hold of a pair. And, in an era when your alternatives might be bloodletting, leeches, and purging, you could see the appeal.