Jim Kozubek in Nautilus:

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe.

A polymathic and pioneering British biologist proposed such a mechanism for how organisms could adapt to their environment, upending the early field of evolutionary biology. For this, Conrad Hal Waddington became recognized as the last Renaissance biologist. This largely had to do with his idea of an “epigenetic landscape”—a metaphor he coined in 1940 to illustrate a theory for how organisms might regulate which of their genes get expressed in response to environmental cues or pressures, leading them down different developmental pathways. It turned out he was onto something: Just a few years after coining the term, it was found that methyl groups—a small molecule made of carbon and hydrogen—could attach to DNA, or to the proteins that house it, and alter gene expression. Changing how a gene is expressed can have drastic consequences: Every cell in our body has the same genes but looks and functions differently only due to the epigenetics that controls when and how genes get turned on. In 2002, one development biologist wondered whether Waddington’s provocative “ideas are relevant tools for understanding the biological problems of today.”

More here.

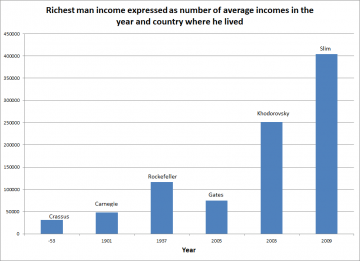

Branko Milanovic over at his website:

Branko Milanovic over at his website: Katherine Angel over at the Verso Blog:

Katherine Angel over at the Verso Blog: Danielle Charette talks to Thomas Piketty in Tocqueville 21:

Danielle Charette talks to Thomas Piketty in Tocqueville 21: Joel Mokyr in Aeon:

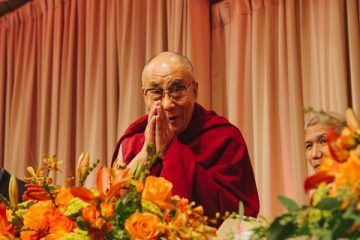

Joel Mokyr in Aeon: “Dalai Lama” is a foreign title. Tibetans refer to him with names like “Precious Protector,” “Wish-Fulfilling Jewel” and “the Presence.” The divide between the Tibetan Buddhist world — which often has included China and Mongolia — and the world beyond has rarely been of particular consequence to the Dalai Lamas, until this one, the 14th, who is the first to spend most of his life in exile; he fled to India in 1959 and has not returned. His biographer, facing the usual problems of recounting the life of a figure still living (the Dalai Lama will be 85 this year), is also faced with the dilemma of describing his life on the world stage (which has been fairly well documented) and his life inside the world of Tibetan Buddhism (which has not). This is the challenge that Alexander Norman, a longtime associate of the Dalai Lama, takes up in his new biography.

“Dalai Lama” is a foreign title. Tibetans refer to him with names like “Precious Protector,” “Wish-Fulfilling Jewel” and “the Presence.” The divide between the Tibetan Buddhist world — which often has included China and Mongolia — and the world beyond has rarely been of particular consequence to the Dalai Lamas, until this one, the 14th, who is the first to spend most of his life in exile; he fled to India in 1959 and has not returned. His biographer, facing the usual problems of recounting the life of a figure still living (the Dalai Lama will be 85 this year), is also faced with the dilemma of describing his life on the world stage (which has been fairly well documented) and his life inside the world of Tibetan Buddhism (which has not). This is the challenge that Alexander Norman, a longtime associate of the Dalai Lama, takes up in his new biography. Kraftwerk

Kraftwerk Black women filmmakers—not invented yesterday and invented by no one but themselves—have persistently been making imaginative work in spite of the many obstacles and restrictions they’ve faced. The sixty plus films included in a recent series at Film Forum, “Black Women: Trailblazing African American Actresses & Images, 1920–2001,” exemplify their innovative and lasting legacies. One of these, Losing Ground (1982), by the filmmaker, playwright, and novelist Kathleen Collins, is a particularly incandescent example of filmmaking as a process of defiant self-creation.

Black women filmmakers—not invented yesterday and invented by no one but themselves—have persistently been making imaginative work in spite of the many obstacles and restrictions they’ve faced. The sixty plus films included in a recent series at Film Forum, “Black Women: Trailblazing African American Actresses & Images, 1920–2001,” exemplify their innovative and lasting legacies. One of these, Losing Ground (1982), by the filmmaker, playwright, and novelist Kathleen Collins, is a particularly incandescent example of filmmaking as a process of defiant self-creation. Viewers of the Oscar-winning film “

Viewers of the Oscar-winning film “ Cancer has always been imagined as a biting, grasping, greedy beast. Hippocrates (or one of his students) is thought to be the first to name the disease karkinos, or crab, as ‘its veins are filled and stretched around like the feet of the animal called crab’. It was an image that would stick, embellished by physicians more deeply and vividly ever after. Like the crab, cancer was tenacious. ‘It is very hardly pulled away from those members, which it doth lay hold on, as the sea crab doth,’ remarked one 16th-century physician. There was no use in cutting away the tumour, just as there was no forcing a ‘Crab to quit what he has grasped betwixt his griping Claws,’ despaired another observer. Cancer the disease was as sneaky as its namesake. ‘It creeps little and little,’ noted one medieval commentator, ‘gnawing and fretting flesh and sinews slowish to the sight as it were a crab.’

Cancer has always been imagined as a biting, grasping, greedy beast. Hippocrates (or one of his students) is thought to be the first to name the disease karkinos, or crab, as ‘its veins are filled and stretched around like the feet of the animal called crab’. It was an image that would stick, embellished by physicians more deeply and vividly ever after. Like the crab, cancer was tenacious. ‘It is very hardly pulled away from those members, which it doth lay hold on, as the sea crab doth,’ remarked one 16th-century physician. There was no use in cutting away the tumour, just as there was no forcing a ‘Crab to quit what he has grasped betwixt his griping Claws,’ despaired another observer. Cancer the disease was as sneaky as its namesake. ‘It creeps little and little,’ noted one medieval commentator, ‘gnawing and fretting flesh and sinews slowish to the sight as it were a crab.’ I am not the first to propose that Transhumanism channels elements of Christian eschatology. In The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace (1999), the science writer Margaret Wertheim argued that Transhumanists seek to “realize a technological substitute for the Christian afterlife” in “digital domains.” She documents, for example, Transhumanist hopes for “whole brain emulation,” whereby—as its most influential proponent, Hans Moravec, envisions it—a “robot brain surgeon” will download your “mind” tissue-layer by tissue-layer, after which you’ll wake up in a simulation. (The useless “meat” leftovers will be trashed.) One’s new cyber-body will now be “limitless” both in time and space, a hope that bears more than a passing resemblance to the “glorified” bodies promised by St. Paul. Moreover, a self made of bits could be backed up, making it possible for one’s “soul-data” to survive a crash or power outage. “As in the New Jerusalem,” Wertheim writes, “‘death would be no more.’”

I am not the first to propose that Transhumanism channels elements of Christian eschatology. In The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace (1999), the science writer Margaret Wertheim argued that Transhumanists seek to “realize a technological substitute for the Christian afterlife” in “digital domains.” She documents, for example, Transhumanist hopes for “whole brain emulation,” whereby—as its most influential proponent, Hans Moravec, envisions it—a “robot brain surgeon” will download your “mind” tissue-layer by tissue-layer, after which you’ll wake up in a simulation. (The useless “meat” leftovers will be trashed.) One’s new cyber-body will now be “limitless” both in time and space, a hope that bears more than a passing resemblance to the “glorified” bodies promised by St. Paul. Moreover, a self made of bits could be backed up, making it possible for one’s “soul-data” to survive a crash or power outage. “As in the New Jerusalem,” Wertheim writes, “‘death would be no more.’” It was Fascism that set image, stage, and performance at the core of an ideology of the state, that merged culture and politics until one was all but indistinguishable from the other, as Walter Benjamin intuited in his much-cited formulation of Fascism as the aestheticization of politics. And as we look on today at the grim return of totalitarian impulses across the globe, we might reflect on how this has been made possible in part by the latent and unresolved question of the relation of politics to culture (and identity) in the modern state.

It was Fascism that set image, stage, and performance at the core of an ideology of the state, that merged culture and politics until one was all but indistinguishable from the other, as Walter Benjamin intuited in his much-cited formulation of Fascism as the aestheticization of politics. And as we look on today at the grim return of totalitarian impulses across the globe, we might reflect on how this has been made possible in part by the latent and unresolved question of the relation of politics to culture (and identity) in the modern state. Mercer has long since been placed in the upper ranks of the great palindromists. Over the years he submitted hundreds of palindromes to the British periodical Notes and Queries, including “Now, Ned, I am a maiden won,” “Nurse, I spy gypsies—run!,” and “Did Hannah say as Hannah did?” But outside the world of word game enthusiasts (a.k.a. logologists), he is largely unknown. This despite being the author of a seven-word, mostly inaccurate synopsis of a complex engineering feat that became one of the most widely known palindromes in English.

Mercer has long since been placed in the upper ranks of the great palindromists. Over the years he submitted hundreds of palindromes to the British periodical Notes and Queries, including “Now, Ned, I am a maiden won,” “Nurse, I spy gypsies—run!,” and “Did Hannah say as Hannah did?” But outside the world of word game enthusiasts (a.k.a. logologists), he is largely unknown. This despite being the author of a seven-word, mostly inaccurate synopsis of a complex engineering feat that became one of the most widely known palindromes in English. Translator’s Introduction: Xu Zhiyong is a legal scholar and former university lecturer from central China with a doctorate from Peking University. He co-founded the

Translator’s Introduction: Xu Zhiyong is a legal scholar and former university lecturer from central China with a doctorate from Peking University. He co-founded the  Up until now, plant-based food companies like Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods, and Quorn have almost singlehandedly worked to lessen the impacts of industrial animal agriculture.

Up until now, plant-based food companies like Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods, and Quorn have almost singlehandedly worked to lessen the impacts of industrial animal agriculture. “You’ve been cheated of your birthright: a complete education.”

“You’ve been cheated of your birthright: a complete education.”