Rainer Zitelmann in Forbes:

Zitelmann: In your book Enlightenment Now, you frequently refer back 200 or 250 years into the past. You make a powerful case that the main line of history since the Enlightenment has been one of progress in all areas of life. But this was also the same period that saw the birth of capitalism. Doesn’t it have to be said that the majority of the positive developments you describe are a result of capitalism?

Pinker: That would be a stretch. Certainly capitalism deserves credit for the spectacular increase in prosperity that the world has enjoyed since the 18th century, including the global east and south in the past forty years. Prosperity, on average, tends to bring other good things in life: democracy, peace, education, women’s rights, safety, environmental protection, to name a few. Also, the spirit of commerce pushes nations toward peace. It’s bad business to kill your customers or your debtors, and when it’s cheaper to buy things than to steal them, nations are not tempted toward bloody conquest. And as morally corrupting as the pursuit of wealth can be, it’s often less murderous than the pursuit of the glory of the nation, race, or religion.

Pinker: That would be a stretch. Certainly capitalism deserves credit for the spectacular increase in prosperity that the world has enjoyed since the 18th century, including the global east and south in the past forty years. Prosperity, on average, tends to bring other good things in life: democracy, peace, education, women’s rights, safety, environmental protection, to name a few. Also, the spirit of commerce pushes nations toward peace. It’s bad business to kill your customers or your debtors, and when it’s cheaper to buy things than to steal them, nations are not tempted toward bloody conquest. And as morally corrupting as the pursuit of wealth can be, it’s often less murderous than the pursuit of the glory of the nation, race, or religion.

But capitalism can coexist with many evils, as we see in authoritarian countries, and progress depended as well on science (particularly advances in public health and medicine), on the ideals of human rights and equality (which propelled the women’s and civil rights movements, and declarations of rights), on movements which led to legislation protecting laborers and the environment, on government provision of public goods like education and infrastructure, on social welfare programs that protect people who are unable to contribute to markets, and on international organizations which encouraged global cooperation and disincentivized war.

More here.

Michael Osterholm, the infectious disease expert who has been warning for a decade and a half that the world will face a pandemic, says the US is ill-prepared to combat the coronavirus due to a shortage of equipment and supplies.

Michael Osterholm, the infectious disease expert who has been warning for a decade and a half that the world will face a pandemic, says the US is ill-prepared to combat the coronavirus due to a shortage of equipment and supplies.

David Cutler: Yeah, one of the continual vexing points about U.S. healthcare is why it’s so expensive. There are a few reasons why the U.S. spends more than other rich countries. Obviously, in poor countries, there’s an enormous difference in the nature of medical care. Relative to other rich countries, I would say there are three principle reasons why the U.S. spends more. The first is that it’s administratively much more costly. So we have lots of people involved in submitting bills, and adjudicating claims and figuring out what services someone is allowed to receive and not allowed to receive and what you need to do in order to receive those services. And all of that involves people, and people are very expensive. And so probably the biggest contributor to the higher spending in the U.S. is that.

David Cutler: Yeah, one of the continual vexing points about U.S. healthcare is why it’s so expensive. There are a few reasons why the U.S. spends more than other rich countries. Obviously, in poor countries, there’s an enormous difference in the nature of medical care. Relative to other rich countries, I would say there are three principle reasons why the U.S. spends more. The first is that it’s administratively much more costly. So we have lots of people involved in submitting bills, and adjudicating claims and figuring out what services someone is allowed to receive and not allowed to receive and what you need to do in order to receive those services. And all of that involves people, and people are very expensive. And so probably the biggest contributor to the higher spending in the U.S. is that. If you tell me that one of the world’s leading neuroscientists has developed a theory of how the brain works that also has implications for the origin and nature of life more broadly, and uses concepts of entropy and information in a central way — well, you know I’m going to be all over that. So it’s my great pleasure to present this conversation with Karl Friston, who has done exactly that. One of the most highly-cited neuroscientists now living, Friston has proposed that we understand the brain in terms of a

If you tell me that one of the world’s leading neuroscientists has developed a theory of how the brain works that also has implications for the origin and nature of life more broadly, and uses concepts of entropy and information in a central way — well, you know I’m going to be all over that. So it’s my great pleasure to present this conversation with Karl Friston, who has done exactly that. One of the most highly-cited neuroscientists now living, Friston has proposed that we understand the brain in terms of a  We tend to think of civility as maintaining a courteous and calm demeanor in political debate. But that can’t be correct. Keeping your cool is good, but courtesy and calmness can also be patronizing. Moreover, fervor is sometimes called for in politics. So civility is better understood as the avoidance of gratuitous escalation and excessive hostility. This allows for political antagonism but recognizes its limits.

We tend to think of civility as maintaining a courteous and calm demeanor in political debate. But that can’t be correct. Keeping your cool is good, but courtesy and calmness can also be patronizing. Moreover, fervor is sometimes called for in politics. So civility is better understood as the avoidance of gratuitous escalation and excessive hostility. This allows for political antagonism but recognizes its limits. B

B One of the earliest mature works in the exhibition, Sex Deviate Being Executed (1964), is also one of Saul’s best. Completed around the same time that Andy Warhol was obsessing over similar material, it shows a gay man smoking a cigarette as he sits in an electric chair. Simple moralistic interpretations get lost in the scene’s queasy virtuosity: the man’s stark profile; his thick, almost monumental arm, which resembles the haunch of an Egyptian sphinx; the decaying blue of his skin against the chair’s lilac. Here and throughout the galleries, the wall texts insist on simple moralistic interpretations anyway—apparently, this painting is about how homophobia, nationalism, and capital punishment are bad, and how a victim “maintains his dignity” in the face of death. The choice of words is unintentionally hilarious, since they appear just a few paces away from a decidedly undignified painting by the name of Human Dignity (1966), in which the title is scrawled on a pair of heaving, planetary breasts. Trust the show’s didactics and you could see Saul as a rough-around-the-edges liberal crusader—but you’d have to ignore the actual works.

One of the earliest mature works in the exhibition, Sex Deviate Being Executed (1964), is also one of Saul’s best. Completed around the same time that Andy Warhol was obsessing over similar material, it shows a gay man smoking a cigarette as he sits in an electric chair. Simple moralistic interpretations get lost in the scene’s queasy virtuosity: the man’s stark profile; his thick, almost monumental arm, which resembles the haunch of an Egyptian sphinx; the decaying blue of his skin against the chair’s lilac. Here and throughout the galleries, the wall texts insist on simple moralistic interpretations anyway—apparently, this painting is about how homophobia, nationalism, and capital punishment are bad, and how a victim “maintains his dignity” in the face of death. The choice of words is unintentionally hilarious, since they appear just a few paces away from a decidedly undignified painting by the name of Human Dignity (1966), in which the title is scrawled on a pair of heaving, planetary breasts. Trust the show’s didactics and you could see Saul as a rough-around-the-edges liberal crusader—but you’d have to ignore the actual works. There are many ways to understand the passage of time—it’s not just one thing after the next, the pinhead of the present gnarling the flesh of your foot as you try, impossibly, to balance upon it. Not just peering through the mist of memory. Not just cutting through the ice ahead. Time moves back and forth, slows down, speeds up, it eddies—it does a lot of eddying. It concentrates itself in one moment and becomes diffuse and vague in another. We’re always in the present, though we can never quite get there, nor can we leave. All of this is what the music of McCoy Tyner, who died on Friday at the age of eighty-one, teaches, though as soon as one tries to paraphrase music in anything other than other music, it’s robbed of some of its magic and much of its meaning.

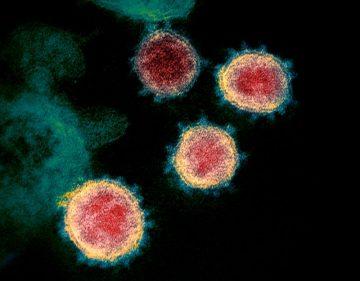

There are many ways to understand the passage of time—it’s not just one thing after the next, the pinhead of the present gnarling the flesh of your foot as you try, impossibly, to balance upon it. Not just peering through the mist of memory. Not just cutting through the ice ahead. Time moves back and forth, slows down, speeds up, it eddies—it does a lot of eddying. It concentrates itself in one moment and becomes diffuse and vague in another. We’re always in the present, though we can never quite get there, nor can we leave. All of this is what the music of McCoy Tyner, who died on Friday at the age of eighty-one, teaches, though as soon as one tries to paraphrase music in anything other than other music, it’s robbed of some of its magic and much of its meaning. As the number of coronavirus infections approaches 100,000 people worldwide, researchers are racing to understand what makes it spread so easily. A handful of genetic and structural analyses have identified a key feature of the virus — a protein on its surface — that might explain why it infects human cells so readily. Other groups are investigating the doorway through which the new coronavirus enters human tissues — a receptor on cell membranes. Both the cell receptor and the virus protein offer potential targets for drugs to block the pathogen, but researchers say it is too early to be sure. “Understanding transmission of the virus is key to its containment and future prevention,” says David Veesler, a structural virologist at the University of Washington in Seattle, who posted his team’s findings about the virus protein on the biomedical preprint server bioRxiv on 20 February

As the number of coronavirus infections approaches 100,000 people worldwide, researchers are racing to understand what makes it spread so easily. A handful of genetic and structural analyses have identified a key feature of the virus — a protein on its surface — that might explain why it infects human cells so readily. Other groups are investigating the doorway through which the new coronavirus enters human tissues — a receptor on cell membranes. Both the cell receptor and the virus protein offer potential targets for drugs to block the pathogen, but researchers say it is too early to be sure. “Understanding transmission of the virus is key to its containment and future prevention,” says David Veesler, a structural virologist at the University of Washington in Seattle, who posted his team’s findings about the virus protein on the biomedical preprint server bioRxiv on 20 February The feeling of being a fraud isn’t new, nor is our preoccupation with it. “All the world’s a stage…And one man in his time plays many parts,” wrote William Shakespeare. The principle of “fake it till you make it” has long propelled incompetents to greatness. The success of phoneys is endlessly fascinating. In the 2000s “On Bullshit”, a book by Harry Frankfurt, a Princeton philosopher, spent many weeks at the top of the New York Times’ bestseller list. But recently we have become fixated on a particular aspect of fraudulence – impostor syndrome – the sense that we are always posturing, that our accomplishments are in some way undeserved, no matter how consistent the evidence to the contrary. Impostor syndrome seems to have become an epidemic. That is partly because we have given the phenomenon a name. Two psychologists, Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, are credited with coining the term in a landmark study in the late 1970s, in which they identified the “internal experience” of feeling like an “intellectual phoney”. But our growing preoccupation with impostorism is also a result of profound social change. In the past most people were employed to make things – and it’s fairly easy to distinguish an expert chairmaker or bricklayer from a novice. Many more of us now work in the service economy: our lives are spent creating impressions rather than tangible items. There is no objective standard for providing a “great customer experience”. To be an excellent manager is a nebulous thing. At every level of every field, the number of roles where achievement is neither entirely measurable nor objective has grown.

The feeling of being a fraud isn’t new, nor is our preoccupation with it. “All the world’s a stage…And one man in his time plays many parts,” wrote William Shakespeare. The principle of “fake it till you make it” has long propelled incompetents to greatness. The success of phoneys is endlessly fascinating. In the 2000s “On Bullshit”, a book by Harry Frankfurt, a Princeton philosopher, spent many weeks at the top of the New York Times’ bestseller list. But recently we have become fixated on a particular aspect of fraudulence – impostor syndrome – the sense that we are always posturing, that our accomplishments are in some way undeserved, no matter how consistent the evidence to the contrary. Impostor syndrome seems to have become an epidemic. That is partly because we have given the phenomenon a name. Two psychologists, Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, are credited with coining the term in a landmark study in the late 1970s, in which they identified the “internal experience” of feeling like an “intellectual phoney”. But our growing preoccupation with impostorism is also a result of profound social change. In the past most people were employed to make things – and it’s fairly easy to distinguish an expert chairmaker or bricklayer from a novice. Many more of us now work in the service economy: our lives are spent creating impressions rather than tangible items. There is no objective standard for providing a “great customer experience”. To be an excellent manager is a nebulous thing. At every level of every field, the number of roles where achievement is neither entirely measurable nor objective has grown.

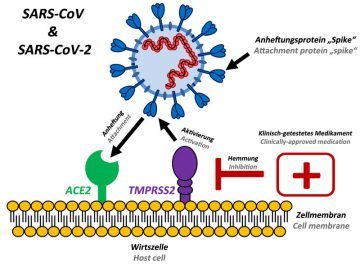

Viruses must enter cells of the human body to cause disease. For this, they attach to suitable cells and inject their genetic information into these cells. Infection biologists from the German Primate Center – Leibniz Institute for Primate Research in Göttingen, together with colleagues at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, have investigated how the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 penetrates cells. They have identified a cellular enzyme that is essential for viral entry into lung cells: the protease TMPRSS2. A clinically proven drug known to be active against TMPRSS2 was found to block SARS-CoV-2 infection and might constitute a novel treatment option (Cell).

Viruses must enter cells of the human body to cause disease. For this, they attach to suitable cells and inject their genetic information into these cells. Infection biologists from the German Primate Center – Leibniz Institute for Primate Research in Göttingen, together with colleagues at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, have investigated how the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 penetrates cells. They have identified a cellular enzyme that is essential for viral entry into lung cells: the protease TMPRSS2. A clinically proven drug known to be active against TMPRSS2 was found to block SARS-CoV-2 infection and might constitute a novel treatment option (Cell). Pinker: That would be a stretch. Certainly capitalism deserves credit for the spectacular increase in prosperity that the world has enjoyed since the 18th century, including the global east and south in the past forty years. Prosperity, on average, tends to bring other good things in life: democracy, peace, education, women’s rights, safety, environmental protection, to name a few. Also, the spirit of commerce pushes nations toward peace. It’s bad business to kill your customers or your debtors, and when it’s cheaper to buy things than to steal them, nations are not tempted toward bloody conquest. And as morally corrupting as the pursuit of wealth can be, it’s often less murderous than the pursuit of the glory of the nation, race, or religion.

Pinker: That would be a stretch. Certainly capitalism deserves credit for the spectacular increase in prosperity that the world has enjoyed since the 18th century, including the global east and south in the past forty years. Prosperity, on average, tends to bring other good things in life: democracy, peace, education, women’s rights, safety, environmental protection, to name a few. Also, the spirit of commerce pushes nations toward peace. It’s bad business to kill your customers or your debtors, and when it’s cheaper to buy things than to steal them, nations are not tempted toward bloody conquest. And as morally corrupting as the pursuit of wealth can be, it’s often less murderous than the pursuit of the glory of the nation, race, or religion. As the coronavirus spreads, it is

As the coronavirus spreads, it is  In the summer of 1348, a ship arrived in England, possibly sailing into the port of Southampton, carrying the most deadly cargo ever to reach the British Isles: Yersinia Pestis – bubonic plague. The highly infectious disease had erupted out of Asia, torn through Europe and finally found its way to England where it would devastate the infrastructure of the country, even wiping out entire towns such as Bristol. The symptoms of such a virulent infection were as dramatic as its spread. First a fever, cold and general flu-like symptoms, followed by blackening buboes forming in the joints – most commonly the groin or the armpits, creating its nickname, the Black Death. Sometimes people survived this stage but most commonly the infection would reach the bloodstream and death was inevitable – and usually swift.

In the summer of 1348, a ship arrived in England, possibly sailing into the port of Southampton, carrying the most deadly cargo ever to reach the British Isles: Yersinia Pestis – bubonic plague. The highly infectious disease had erupted out of Asia, torn through Europe and finally found its way to England where it would devastate the infrastructure of the country, even wiping out entire towns such as Bristol. The symptoms of such a virulent infection were as dramatic as its spread. First a fever, cold and general flu-like symptoms, followed by blackening buboes forming in the joints – most commonly the groin or the armpits, creating its nickname, the Black Death. Sometimes people survived this stage but most commonly the infection would reach the bloodstream and death was inevitable – and usually swift. The lions and leopards of Gir National Park, in Gujarat, India, normally do not get along. “They compete with each other” for space and food, said Stotra Chakrabarti, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota who studies animal behavior. “They are at perpetual odds.” But about a year ago, a young lioness in the park put this enmity aside. She adopted a baby leopard. The 2-month-old cub — all fuzzy ears and blue eyes — was adorable, and the lioness spent weeks nursing, feeding and caring for him until he died. She treated him as if one of her own two sons, who were about the same age. This was a rare case of cross-species adoption in the wild, and the only documented example involving animals that are normally strong competitors, Dr. Chakrabarti said. He

The lions and leopards of Gir National Park, in Gujarat, India, normally do not get along. “They compete with each other” for space and food, said Stotra Chakrabarti, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota who studies animal behavior. “They are at perpetual odds.” But about a year ago, a young lioness in the park put this enmity aside. She adopted a baby leopard. The 2-month-old cub — all fuzzy ears and blue eyes — was adorable, and the lioness spent weeks nursing, feeding and caring for him until he died. She treated him as if one of her own two sons, who were about the same age. This was a rare case of cross-species adoption in the wild, and the only documented example involving animals that are normally strong competitors, Dr. Chakrabarti said. He