Jules Evans in Aeon:

When I was a teenager, I came across Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945). I was so inspired by its array of mystical jewels that, like a magpie, I stole it from my school’s library. I still have that copy, sitting beside me. Next, I devoured his book The Doors of Perception (1954), and secretly converted to psychedelic mysticism. It was thanks to Huxley that I refused to get confirmed, thanks to him that my friends and I spent our adolescence trying to storm heaven on LSD, with mixed results. Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy has stayed with me through my life. He’s been my spirit-grandad. And yet, in the past few years, as I’ve researched his life, I find myself increasingly arguing with Grandad. What if his philosophy isn’t true?

When I was a teenager, I came across Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945). I was so inspired by its array of mystical jewels that, like a magpie, I stole it from my school’s library. I still have that copy, sitting beside me. Next, I devoured his book The Doors of Perception (1954), and secretly converted to psychedelic mysticism. It was thanks to Huxley that I refused to get confirmed, thanks to him that my friends and I spent our adolescence trying to storm heaven on LSD, with mixed results. Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy has stayed with me through my life. He’s been my spirit-grandad. And yet, in the past few years, as I’ve researched his life, I find myself increasingly arguing with Grandad. What if his philosophy isn’t true?

The phrase ‘perennial philosophy’ was first coined by the Renaissance humanist Agostino Steuco in 1540. It referred to the idea that there is a core of shared wisdom in all religions, and to the attempt by Marsilio Ficino’s Neoplatonist school to synthesise that wisdom into one transcultural philosophy. This philosophy, writes Huxley, ‘is immemorial and universal. Rudiments of the perennial philosophy may be found among the traditionary lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions.’ As Huxley argues, there is a lot of agreement between proponents of classical theism in Platonic, Christian, Muslim, Hindu and Jewish philosophy over three main points: God is unconditioned eternal Being, our consciousness is a reflection or spark of that, and we can find our flourishing or bliss in the realisation of this. But what about Buddhism’s theory of anatta, or ‘no self’? Huxley suggests that the Buddha meant the ordinary ego doesn’t exist, but there is still an ‘unconditioned essence’ (which is arguably true of some forms of Buddhism but not others). I suspect scholars of Taoism would object to equating the Tao with the God of classical theism. As for ‘the traditional lore of primitive peoples’, I’m sure Huxley didn’t know enough to say.

Still, one can see striking similarities in the mystical ideas and practices of the main religious traditions. The common goal is to overcome the ego and awaken to reality. Ordinary egocentric reality is considered to be a trancelike succession of automatic impulses and attachments. The path to awakening involves daily training in contemplation, recollection, non-attachment, charity and love. When one has achieved ‘total selflessness’, one realises the true nature of reality. There are different paths up the mystic mountain, but Huxley suggests that the peak experience is the same in all traditions: a wordless, imageless encounter with the Pure Light of the divine.

More here.

It’s hard to make decisions that will change your life. It’s even harder to make a decision if you know that the outcome could change who you are. Our preferences are determined by who we are, and they might be quite different after a decision is made — and there’s no rational way of taking that into account. Philosopher L.A. Paul has been investigating these transformative experiences — from getting married, to having a child, to going to graduate school — with an eye to deciding how to live in the face of such choices. Of course we can ask people who have made such a choice what they think, but that doesn’t tell us whether the choice is a good one from the standpoint of our current selves, those who haven’t taken the plunge. We talk about what this philosophical conundrum means for real-world decisions, attitudes towards religious faith, and the tricky issue of what it means to be authentic to yourself when your “self” keeps changing over time.

It’s hard to make decisions that will change your life. It’s even harder to make a decision if you know that the outcome could change who you are. Our preferences are determined by who we are, and they might be quite different after a decision is made — and there’s no rational way of taking that into account. Philosopher L.A. Paul has been investigating these transformative experiences — from getting married, to having a child, to going to graduate school — with an eye to deciding how to live in the face of such choices. Of course we can ask people who have made such a choice what they think, but that doesn’t tell us whether the choice is a good one from the standpoint of our current selves, those who haven’t taken the plunge. We talk about what this philosophical conundrum means for real-world decisions, attitudes towards religious faith, and the tricky issue of what it means to be authentic to yourself when your “self” keeps changing over time.

To walk from south to north on the peripatos, the path encircling the Acropolis of Athens – as I did one golden morning in December last year – takes you past the boisterous crowds swarming the stone seats of the Theatre of Dionysus. The path then threads just below the partially restored colonnades of the monumental Propylaea, which was thronged that morning with visitors pausing to chat and take photographs before they clambered past that monumental gateway up to the Parthenon. Proceed further along the curved trail and, like an epiphany, you will find yourself in the wilder north-facing precincts of that ancient outcrop. In the section known as the Long Rocks there are a series of alcoves of varying sizes, named ingloriously by the archaeologists as caves A, B, C and D. In its unanticipated tranquility, this stretch of rock still seems to host the older gods.

To walk from south to north on the peripatos, the path encircling the Acropolis of Athens – as I did one golden morning in December last year – takes you past the boisterous crowds swarming the stone seats of the Theatre of Dionysus. The path then threads just below the partially restored colonnades of the monumental Propylaea, which was thronged that morning with visitors pausing to chat and take photographs before they clambered past that monumental gateway up to the Parthenon. Proceed further along the curved trail and, like an epiphany, you will find yourself in the wilder north-facing precincts of that ancient outcrop. In the section known as the Long Rocks there are a series of alcoves of varying sizes, named ingloriously by the archaeologists as caves A, B, C and D. In its unanticipated tranquility, this stretch of rock still seems to host the older gods. If self-help books soothe people whose lives feel like open wounds, there’s perhaps no class of people who needs the category more than writers do. It was only lately that I realized I was drawn to self-improvement books, and the certainty they sell, because I was a writer—because the life of a writer is marked by insecurity both emotional and financial, rejection at seemingly every turn, and the fact that no one has any idea what you’re talking about when you say writing is hard and you hate it. I think of Annie Dillard, in The Writing Life, who says as much to a local ferryman and then hastily backtracks. “But I rallied and mustered and said that the idea was to learn things; that you learn a thing and then as a matter of course you learn the next thing, and the next thing,” she writes. “As I spoke he nodded precisely in the way that one nods at the utterances of the deranged. ‘And then,’ I finished brightly, ‘you die!’”

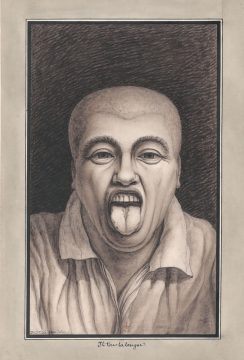

If self-help books soothe people whose lives feel like open wounds, there’s perhaps no class of people who needs the category more than writers do. It was only lately that I realized I was drawn to self-improvement books, and the certainty they sell, because I was a writer—because the life of a writer is marked by insecurity both emotional and financial, rejection at seemingly every turn, and the fact that no one has any idea what you’re talking about when you say writing is hard and you hate it. I think of Annie Dillard, in The Writing Life, who says as much to a local ferryman and then hastily backtracks. “But I rallied and mustered and said that the idea was to learn things; that you learn a thing and then as a matter of course you learn the next thing, and the next thing,” she writes. “As I spoke he nodded precisely in the way that one nods at the utterances of the deranged. ‘And then,’ I finished brightly, ‘you die!’” Like other early-modern architects, Lequeu’s drawings explore analogies between bodies and buildings and the erotic, multisensory dimensions of architectural design. In his annotations, he often describes in compulsive detail not only how buildings look but also how they feel, smell, and even taste—which admittedly sounds weird until you read Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’s Le génie de l’architecture, ou L’analogie de cet art avec nos sensations (The Genius of Architecture; or, The Analogy of That Art with Our Sensations, 1780), a building treatise informed by eighteenth-century sensationalist and materialist philosophy, or Jean-François de Bastide’s La petite maison (The Little House, 1758). The latter text, a libertine novella centering on a marquis who bets a young ingénue that he can seduce her by taking her on a tour of his “pleasure house” (maison de plaisance) outside of Paris, contains descriptions of scented walls and furnishings, a mechanical dining table that drops through a trapdoor, and a mirrored boudoir disguised as a trompe l’oeil forest that readily call to mind the drawings of Lequeu.

Like other early-modern architects, Lequeu’s drawings explore analogies between bodies and buildings and the erotic, multisensory dimensions of architectural design. In his annotations, he often describes in compulsive detail not only how buildings look but also how they feel, smell, and even taste—which admittedly sounds weird until you read Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’s Le génie de l’architecture, ou L’analogie de cet art avec nos sensations (The Genius of Architecture; or, The Analogy of That Art with Our Sensations, 1780), a building treatise informed by eighteenth-century sensationalist and materialist philosophy, or Jean-François de Bastide’s La petite maison (The Little House, 1758). The latter text, a libertine novella centering on a marquis who bets a young ingénue that he can seduce her by taking her on a tour of his “pleasure house” (maison de plaisance) outside of Paris, contains descriptions of scented walls and furnishings, a mechanical dining table that drops through a trapdoor, and a mirrored boudoir disguised as a trompe l’oeil forest that readily call to mind the drawings of Lequeu. Viola Roseboro’ (apostrophe intentional), the larger-than-life fiction editor at McClure’s, haunted magazine offices from the 1890s to the Jazz Age. A reader, editor, and semiprofessional wit, she discovered or mentored O. Henry, Willa Cather, and Jack London, among many others. Today she is nearly completely forgotten.

Viola Roseboro’ (apostrophe intentional), the larger-than-life fiction editor at McClure’s, haunted magazine offices from the 1890s to the Jazz Age. A reader, editor, and semiprofessional wit, she discovered or mentored O. Henry, Willa Cather, and Jack London, among many others. Today she is nearly completely forgotten. When I was a teenager, I came across Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945). I was so inspired by its array of mystical jewels that, like a magpie, I stole it from my school’s library. I still have that copy, sitting beside me. Next, I devoured his book The Doors of Perception (1954), and secretly converted to psychedelic mysticism. It was thanks to Huxley that I refused to get confirmed, thanks to him that my friends and I spent our adolescence trying to storm heaven on LSD, with mixed results. Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy has stayed with me through my life. He’s been my spirit-grandad. And yet, in the past few years, as I’ve researched his life, I find myself increasingly arguing with Grandad. What if his philosophy isn’t true?

When I was a teenager, I came across Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945). I was so inspired by its array of mystical jewels that, like a magpie, I stole it from my school’s library. I still have that copy, sitting beside me. Next, I devoured his book The Doors of Perception (1954), and secretly converted to psychedelic mysticism. It was thanks to Huxley that I refused to get confirmed, thanks to him that my friends and I spent our adolescence trying to storm heaven on LSD, with mixed results. Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy has stayed with me through my life. He’s been my spirit-grandad. And yet, in the past few years, as I’ve researched his life, I find myself increasingly arguing with Grandad. What if his philosophy isn’t true? They asked Katherine Johnson for the moon, and she gave it to them. Wielding little more than a pencil, a slide rule and one of the finest mathematical minds in the country, Mrs. Johnson, who died at 101 on Monday at a retirement home in Newport News, Va., calculated the precise trajectories that would let Apollo 11 land on the moon in 1969 and, after Neil Armstrong’s history-making moonwalk, let it return to Earth. A single error, she well knew, could have dire consequences for craft and crew. Her impeccable calculations had already helped plot the successful flight of Alan B. Shepard Jr., who became the first American in space when his Mercury spacecraft went aloft in 1961. The next year, she likewise helped make it possible for John Glenn, in the Mercury vessel Friendship 7, to become the first American to orbit the Earth. Yet throughout Mrs. Johnson’s 33 years in NASA’s Flight Research Division — the office from which the American space program sprang — and for decades afterward, almost no one knew her name.

They asked Katherine Johnson for the moon, and she gave it to them. Wielding little more than a pencil, a slide rule and one of the finest mathematical minds in the country, Mrs. Johnson, who died at 101 on Monday at a retirement home in Newport News, Va., calculated the precise trajectories that would let Apollo 11 land on the moon in 1969 and, after Neil Armstrong’s history-making moonwalk, let it return to Earth. A single error, she well knew, could have dire consequences for craft and crew. Her impeccable calculations had already helped plot the successful flight of Alan B. Shepard Jr., who became the first American in space when his Mercury spacecraft went aloft in 1961. The next year, she likewise helped make it possible for John Glenn, in the Mercury vessel Friendship 7, to become the first American to orbit the Earth. Yet throughout Mrs. Johnson’s 33 years in NASA’s Flight Research Division — the office from which the American space program sprang — and for decades afterward, almost no one knew her name.

It is the end of the Trojan War. Hecuba, the noble queen of Troy, has endured many losses: her husband, her children, her fatherland, destroyed by fire. And yet she remains an admirable person—loving, capable of trust and friendship, combining autonomous action with extensive concern for others. But then she suffers a betrayal that cuts deep, traumatizing her entire personality. A close friend, Polymestor, to whom she has entrusted the care of her last remaining child, murders the child for money. That is the central event in Euripides’s Hecuba (424 BCE), an anomalous version of the Trojan war story, shocking in its moral ugliness, and yet one of the most insightful dramas in the tragic canon.

It is the end of the Trojan War. Hecuba, the noble queen of Troy, has endured many losses: her husband, her children, her fatherland, destroyed by fire. And yet she remains an admirable person—loving, capable of trust and friendship, combining autonomous action with extensive concern for others. But then she suffers a betrayal that cuts deep, traumatizing her entire personality. A close friend, Polymestor, to whom she has entrusted the care of her last remaining child, murders the child for money. That is the central event in Euripides’s Hecuba (424 BCE), an anomalous version of the Trojan war story, shocking in its moral ugliness, and yet one of the most insightful dramas in the tragic canon. Up until now, plant-based food companies like Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods, and Quorn have almost singlehandedly worked to lessen the impacts of industrial animal agriculture.

Up until now, plant-based food companies like Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods, and Quorn have almost singlehandedly worked to lessen the impacts of industrial animal agriculture. In the summer of 1917, a group of university students in Munich invited Max Weber to launch a lecture series on “intellectual work as a vocation” with a talk about the scholar’s work. He was, in a way, an odd choice. Fifty-three at the time, Weber hadn’t held an academic job in over a decade. His career had begun promisingly, but in 1899 he suffered a nervous breakdown and gave up his position as a professor of economics at the University of Heidelberg. Supported by the inheritance of his wife, Marianne, he spent years going from clinic to clinic in search of relief. He continued to write about lifelong concerns such as the social effects of religion, contributing articles to scholarly journals while also writing journalistic essays for newspapers and periodicals. Yet in 1917, his last major publication was The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which had originally appeared as two separate essays in 1904 and 1905.

In the summer of 1917, a group of university students in Munich invited Max Weber to launch a lecture series on “intellectual work as a vocation” with a talk about the scholar’s work. He was, in a way, an odd choice. Fifty-three at the time, Weber hadn’t held an academic job in over a decade. His career had begun promisingly, but in 1899 he suffered a nervous breakdown and gave up his position as a professor of economics at the University of Heidelberg. Supported by the inheritance of his wife, Marianne, he spent years going from clinic to clinic in search of relief. He continued to write about lifelong concerns such as the social effects of religion, contributing articles to scholarly journals while also writing journalistic essays for newspapers and periodicals. Yet in 1917, his last major publication was The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which had originally appeared as two separate essays in 1904 and 1905. Antisocial is, among other things, a tale of two Mikes. Mike Cernovich was a law student, nutrition blogger, self-help author and generic Twitter troll before hitting the jackpot as a tireless online booster for the man he had previously called “Donald Chump”. The similarly directionless Mike Peinovich, AKA Mike Enoch, took an even uglier path: he ended up calling for a white ethnostate and making Holocaust jokes on his podcast the Daily Shoah. One is effectively a neo-Nazi, the other just an agile hustler. Whether that distinction matters when you consider the damage both have done to political discourse is one of the urgent questions of this compelling book.

Antisocial is, among other things, a tale of two Mikes. Mike Cernovich was a law student, nutrition blogger, self-help author and generic Twitter troll before hitting the jackpot as a tireless online booster for the man he had previously called “Donald Chump”. The similarly directionless Mike Peinovich, AKA Mike Enoch, took an even uglier path: he ended up calling for a white ethnostate and making Holocaust jokes on his podcast the Daily Shoah. One is effectively a neo-Nazi, the other just an agile hustler. Whether that distinction matters when you consider the damage both have done to political discourse is one of the urgent questions of this compelling book. On a sunny Sunday afternoon in early June 1967, several hundred Clevelanders crowded outside the offices of the Negro Industrial Economic union in lower University Circle. None of those gathered, including a collection of the top black athletes of that time, realized the significance of what would happen in that building on this day. Muhammad Ali, the most polarizing figure in the country, was inside being grilled by

On a sunny Sunday afternoon in early June 1967, several hundred Clevelanders crowded outside the offices of the Negro Industrial Economic union in lower University Circle. None of those gathered, including a collection of the top black athletes of that time, realized the significance of what would happen in that building on this day. Muhammad Ali, the most polarizing figure in the country, was inside being grilled by  The week before Christmas, Richard Leakey, the Kenyan paleoanthropologist and conservationist, celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday. He is lucky to have reached the milestone. A tall man with the burned and scarred skin that results from a life lived outdoors, Leakey has survived two kidney transplants, one liver transplant, and a devastating airplane crash that cost him both of his legs below the knee. For the past quarter century, he has moved around on prosthetic limbs concealed beneath his trousers. In his home town of Nairobi, Leakey keeps an office in an unlikely sort of place—the annex building of a suburban shopping mall. His desk and chair fill most of his cubicle, which has a window that looks onto a parking lot.

The week before Christmas, Richard Leakey, the Kenyan paleoanthropologist and conservationist, celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday. He is lucky to have reached the milestone. A tall man with the burned and scarred skin that results from a life lived outdoors, Leakey has survived two kidney transplants, one liver transplant, and a devastating airplane crash that cost him both of his legs below the knee. For the past quarter century, he has moved around on prosthetic limbs concealed beneath his trousers. In his home town of Nairobi, Leakey keeps an office in an unlikely sort of place—the annex building of a suburban shopping mall. His desk and chair fill most of his cubicle, which has a window that looks onto a parking lot.