Paul Reitter And Chad Wellmon in The Chronicle Review:

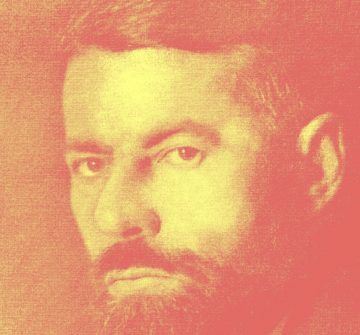

In the summer of 1917, a group of university students in Munich invited Max Weber to launch a lecture series on “intellectual work as a vocation” with a talk about the scholar’s work. He was, in a way, an odd choice. Fifty-three at the time, Weber hadn’t held an academic job in over a decade. His career had begun promisingly, but in 1899 he suffered a nervous breakdown and gave up his position as a professor of economics at the University of Heidelberg. Supported by the inheritance of his wife, Marianne, he spent years going from clinic to clinic in search of relief. He continued to write about lifelong concerns such as the social effects of religion, contributing articles to scholarly journals while also writing journalistic essays for newspapers and periodicals. Yet in 1917, his last major publication was The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which had originally appeared as two separate essays in 1904 and 1905.

In the summer of 1917, a group of university students in Munich invited Max Weber to launch a lecture series on “intellectual work as a vocation” with a talk about the scholar’s work. He was, in a way, an odd choice. Fifty-three at the time, Weber hadn’t held an academic job in over a decade. His career had begun promisingly, but in 1899 he suffered a nervous breakdown and gave up his position as a professor of economics at the University of Heidelberg. Supported by the inheritance of his wife, Marianne, he spent years going from clinic to clinic in search of relief. He continued to write about lifelong concerns such as the social effects of religion, contributing articles to scholarly journals while also writing journalistic essays for newspapers and periodicals. Yet in 1917, his last major publication was The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which had originally appeared as two separate essays in 1904 and 1905.

Still, it was understandable why the students in Munich were drawn to Weber. They belonged to the Free Student Alliance, an organization devoted to championing the lofty ideals of the German research university — the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, Bildung or moral education, academic freedom, and the democratization of all these goods — at a time when those ideals appeared to be imperiled by disciplinary specialization, state intervention, the influence of industrial capitalism, and the war. Writing over the years as a kind of insider-outsider, Weber had distinguished himself as an extraordinarily erudite and forceful defender of an ideal university.

More here.