Category: Recommended Reading

This Side Of Paradise: A Letter From F. Scott Fitzgerald, Quarantined In The South Of France

Nick Farriella in McSweeney’s:

Dearest Rosemary,

Dearest Rosemary,

It was a limpid dreary day, hung as in a basket from a single dull star. I thank you for your letter. Outside, I perceive what may be a collection of fallen leaves tussling against a trash can. It rings like jazz to my ears. The streets are that empty. It seems as though the bulk of the city has retreated to their quarters, rightfully so. At this time, it seems very poignant to avoid all public spaces. Even the bars, as I told Hemingway, but to that he punched me in the stomach, to which I asked if he had washed his hands. He hadn’t. He is much the denier, that one. Why, he considers the virus to be just influenza. I’m curious of his sources.

The officials have alerted us to ensure we have a month’s worth of necessities. Zelda and I have stocked up on red wine, whiskey, rum, vermouth, absinthe, white wine, sherry, gin, and lord, if we need it, brandy. Please pray for us.

More here.

Friday Poem

Jasmine

Almost the twenty-first century” —

how quickly the thought will grow dated,

even quaint.

Our hopes, our future,

will pass like the hopes and futures of others.

And all our anxieties and terrors,

nights of sleeplessness,

griefs,

will appear then as they truly are —

Stumbling, delirious bees in the tea scent of jasmine.

by Jane Hirshfield

from Brain Pickings

‘America First’ Is Making the Pandemic Worse

Kori Schake in The Atlantic:

The National Security Strategy that President Donald Trump published during his first year in office describes an “America First foreign policy in action.” In an introductory message, the president declares, “We are prioritizing the interests of our citizens and protecting our sovereign rights as a nation.” He insists that “‘America First’ is not America alone.” His national security adviser and chief economic adviser at the time assured the public, “America will not lead from behind. This administration will restore confidence in American leadership as we serve the American people.” While there have been reasons previously to question the approach, the coronavirus has posed the first real international crisis of Trump’s presidency. And judged from the administration’s actions, America First foreign policy in action isn’t restoring confidence in American leadership, and it isn’t serving the American people particularly well.

Rather than lead a cooperative international response, Trump has sought to blame the outbreak on China and then on Europe. America’s NATO allies were given no advance warning of the travel ban on their countries. A virtual meeting of the G-7 came at French President Emmanuel Macron’s instigation, not at Trump’s, even though the United States is chairing that group of the world’s leading economies. China’s leaders are gleefully running up their score in the great power competition by being generous where we are stingy.

The Pandemic Is Showing Us How to Live with Uncertainty

Scott Koenig in Nautilus:

During the Spanish flu of 1918, it was Vick’s VapoRub. During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, it was canned food. Now, as the number of cases of COVID-19 grows worldwide, it’s, among other things, toilet paper. In times of precarity, people often resort to hoarding resources they think are likely to become scarce—panic buying, as it’s sometimes called. And while it’s easy to dismiss as an overreaction, it underscores just how difficult it can be, for both the general public and public health authorities, to choose the right response to a dangerous, rapidly evolving situation.

During the Spanish flu of 1918, it was Vick’s VapoRub. During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, it was canned food. Now, as the number of cases of COVID-19 grows worldwide, it’s, among other things, toilet paper. In times of precarity, people often resort to hoarding resources they think are likely to become scarce—panic buying, as it’s sometimes called. And while it’s easy to dismiss as an overreaction, it underscores just how difficult it can be, for both the general public and public health authorities, to choose the right response to a dangerous, rapidly evolving situation.

“One of the reasons we have so many challenges is that there’s just so much uncertainty, especially in the early days of an outbreak,” said Glen Nowak, a former director of media relations and communications at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), now a professor of advertising at the University of Georgia. Even for authorities, Nowak said, the number of moving parts and open questions during a public health crisis—where the disease originated, how infectious and deadly it is, how many people are already infected and who’s at risk—can be overwhelming. This means that the rest of us, despite the experts’ best efforts at communicating, often have to make do with limited and possibly even conflicting information. “What people are often thinking of, from a psychological standpoint, is ‘What is the best way for me to cope with this uncertainty?’” Nowak told me. For many people, coping may take the form of hoarding supplies in an attempt to assert control over the situation. Or it might mean looking to others for guidance—and if everyone else in your community is taking all the toilet paper, are you going to be the odd one out?

More here.

Thursday, March 19, 2020

How Rembrandt, Titian and Caravaggio tackled pestilence

Jonathan Jones in The Guardian:

It seems incredible that we should find common cause with the people of 500 years ago, who faced disease without any understanding or remotely adequate treatment. But on Sunday, Pope Francis walked the streets of Rome, left empty by coronavirus, to visit the church of San Marcello on the Corso – and revere a cross that supposedly protected Rome from plague in 1522.

We now find ourselves in the same plight – menaced by an illness that seems to have the upper hand and that is turning our assumptions upside down. Even the methods being used, including quarantine, come from that plagued past. As does much of Europe’s greatest art. These masterpieces might console us, or make us see this unfamiliar moment in a new light, or even give us practical ideas to cope. Here are some of those images, perhaps to be used as guides – for Rembrandt, Titian and Caravaggio trod this path before us.

More here.

The first lines of 10 classic novels, rewritten for social distancing

Jessie Gaynor in Lit Hub:

Moby-Dick

FaceTime me, Ishmael.

Jane Eyre

There was every possibility of taking a walk that day, as long as we kept six feet between us and the others on the path.

Pride and Prejudice

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be hoarding toilet paper.

More here.

Victorian Technology

Marta Figlerowicz at Public Books:

In the late 19th century—as in the early 21st century—ordinary people were swept up in the new craze of portrait photography. “Our loathsome society rushed, like Narcissus,” writes Charles Baudelaire, “to contemplate its trivial image on a metallic plate.” It’s easy to laugh at this sentence, both at how familiar and how distant it sounds today. Baudelaire’s disgust does echo our contemporary gripes about iPhones and selfie sticks. And yet, it does so in a loftier, more genteel idiom. Baudelaire’s unintended proto-image of the smartphone (as a steampunk “metallic plate”) carries Romantic force. The quotation—like, perhaps, the selfie itself—seems to capture a crucial, undefinable moment: the split second of our loss of technological innocence.

In the late 19th century—as in the early 21st century—ordinary people were swept up in the new craze of portrait photography. “Our loathsome society rushed, like Narcissus,” writes Charles Baudelaire, “to contemplate its trivial image on a metallic plate.” It’s easy to laugh at this sentence, both at how familiar and how distant it sounds today. Baudelaire’s disgust does echo our contemporary gripes about iPhones and selfie sticks. And yet, it does so in a loftier, more genteel idiom. Baudelaire’s unintended proto-image of the smartphone (as a steampunk “metallic plate”) carries Romantic force. The quotation—like, perhaps, the selfie itself—seems to capture a crucial, undefinable moment: the split second of our loss of technological innocence.

more here.

Percy Bysshe Shelley: “England in 1819”

Christopher Spaide at Poetry Magazine:

One of English’s great, scornful, scorching political poems was premiered in an unassuming place: the postscript of a letter: “What a state England is in! But you will never write politics.” It was December 1819, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, then 27, was writing another pushily impassioned letter to Leigh Hunt, a poet, a radical, and the founding editor of the Examiner. Since 1818, Shelley and his wife, the novelist Mary Shelley, had been restless expatriates in Italy, never in any one city for long. Dead by drowning three years later, he never revisited his home country and never quite escaped its orbit, gravitationally tugged back by England’s tumultuous politics. However desperate for Hunt’s dispatches (“Why don’t you write to us?” the letter opens), Shelley, never afraid to speak his mind, thought his friend deserved a “scolding”: “I wish, then, that you would write a paper in the Examiner, on the actual state of the country, and what, under all the circumstances of the conflicting passions and interests of men, we are to expect.” Surely Shelley meant wish wholeheartedly, but he was also setting up Hunt for a surprise present, which he introduced, with coy calm, in his postscript. “I send you a sonnet. I do not expect you to publish it, but you may show it to whom you please.”

One of English’s great, scornful, scorching political poems was premiered in an unassuming place: the postscript of a letter: “What a state England is in! But you will never write politics.” It was December 1819, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, then 27, was writing another pushily impassioned letter to Leigh Hunt, a poet, a radical, and the founding editor of the Examiner. Since 1818, Shelley and his wife, the novelist Mary Shelley, had been restless expatriates in Italy, never in any one city for long. Dead by drowning three years later, he never revisited his home country and never quite escaped its orbit, gravitationally tugged back by England’s tumultuous politics. However desperate for Hunt’s dispatches (“Why don’t you write to us?” the letter opens), Shelley, never afraid to speak his mind, thought his friend deserved a “scolding”: “I wish, then, that you would write a paper in the Examiner, on the actual state of the country, and what, under all the circumstances of the conflicting passions and interests of men, we are to expect.” Surely Shelley meant wish wholeheartedly, but he was also setting up Hunt for a surprise present, which he introduced, with coy calm, in his postscript. “I send you a sonnet. I do not expect you to publish it, but you may show it to whom you please.”

more here.

Julie Andrews’s Post-Poppins Life

Lindsay Zoladz at Bookforum:

On screen and off, Edwards came to see something in Andrews that Kael—and other critics like her—could not. Underneath her wimple, as the nuns say of Maria, Andrews had curlers in her hair. Yes, in nearly every role she comports herself like the queen of some imaginary, borderless kingdom. But there is also an odd tension beneath the surface of Andrews’s most ostensibly wholesome performances—the kind that can drive a viewer to all sorts of wild speculation about what Mary Poppins gets up to on her days off, and that can inspire an entire volume of queer theory that hinges upon a dissident reading of the boyish Maria von Trapp (see: Stacy Wolf’s 2002 A Problem Like Maria: Gender and Sexuality in the American Musical). Pinning down the hidden complexities and contradictions of Andrews’s stardom is a bit like holding a moonbeam in your hand. As composer and broadcaster Neil Brand put it to The Guardian last year, Andrews may just be “the politest rebel in all cinema.”

On screen and off, Edwards came to see something in Andrews that Kael—and other critics like her—could not. Underneath her wimple, as the nuns say of Maria, Andrews had curlers in her hair. Yes, in nearly every role she comports herself like the queen of some imaginary, borderless kingdom. But there is also an odd tension beneath the surface of Andrews’s most ostensibly wholesome performances—the kind that can drive a viewer to all sorts of wild speculation about what Mary Poppins gets up to on her days off, and that can inspire an entire volume of queer theory that hinges upon a dissident reading of the boyish Maria von Trapp (see: Stacy Wolf’s 2002 A Problem Like Maria: Gender and Sexuality in the American Musical). Pinning down the hidden complexities and contradictions of Andrews’s stardom is a bit like holding a moonbeam in your hand. As composer and broadcaster Neil Brand put it to The Guardian last year, Andrews may just be “the politest rebel in all cinema.”

more here.

No patient is an island

Anita Ho in Aeon:

‘I wouldn’t show them the note,’ a retired nurse, told my mother. It was a request to meet with my father’s physicians. He had undergone a cardiac surgery, and soon after became lethargic and difficult to rouse. The nurses thought he was simply fatigued from his procedure, and my mother didn’t want to question their professional judgment. Two days later, my father suffered an acute respiratory failure and was rushed to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was intubated and remained dependent on a respirator for days. The nurses told my mother that the doctors were considering a tracheostomy, but up to that point no ICU physician (called an ‘intensivist’) had so much as talked to my family.

‘I wouldn’t show them the note,’ a retired nurse, told my mother. It was a request to meet with my father’s physicians. He had undergone a cardiac surgery, and soon after became lethargic and difficult to rouse. The nurses thought he was simply fatigued from his procedure, and my mother didn’t want to question their professional judgment. Two days later, my father suffered an acute respiratory failure and was rushed to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was intubated and remained dependent on a respirator for days. The nurses told my mother that the doctors were considering a tracheostomy, but up to that point no ICU physician (called an ‘intensivist’) had so much as talked to my family.

Intensivists were not at the bedside during the limited visiting hours and, as they rotated, a series of different intensivists attended to my father. So my mother was left to wait outside the ICU in the remote chance that she would run into my father’s doctor, but nobody told her the name of the attending physician du jour, and the doctors’ faces were often hidden behind surgical masks as they walked the halls. So, with my help, she had drawn up the note, requesting a meeting. But it was to no avail. ‘The doctors might think your family is difficult,’ the nurse said.

I wondered why the doctors didn’t hold a family meeting to discuss my father’s prognosis and clinical options. While my mother wanted to speak to at least one of the intensivists, attempts to make appointments were met with reluctance. The nurses said the doctors were busy, that they had to uphold patient privacy and confidentiality. My mother started to blame herself for not insisting on further investigation regarding my father’s lethargy, and she was anxious about the lack of information. Worse, the insinuation that she would be bothering the busy clinicians for wanting a meeting with them intimidated her. She was sternly warned by a nurse not to overstay the visiting hours. I am a bioethicist who has worked alongside clinicians in supporting patients and families making complex and rending care decisions. I have seen how physicians are bombarded with demands. Meeting with families requires not only coordination but energy: it is emotionally draining for clinicians to share grim prognoses with patients and families.

More here.

Could consciousness be a brain process?

John Heil in IAI News:

Why is consciousness so perplexing to so many? Perhaps, owing to our being conscious, we regard ourselves as experts on the matter, and it seems to us blindingly obvious that consciousness could not possibly be a brain state or process. We have a front-row seat, an unmediated first-hand awareness of what conscious experiences are like, and we know well-enough what brain processes are like. The two could not be more different. In the hands of philosophers, this sentiment is transmuted into the doctrine that consciousness cannot be identified with, or ‘reduced to’, anything physical. The reduction in question must be a relation among explanations, or predicates, not as it is sometimes cast, a relation among properties. What would it be to reduce something to something else? If the As are not reducible to the Bs, explanations of the As could not be derived from explanations of the Bs, nor could A-terms be analysed or paraphrased in a B-vocabulary.

Why is consciousness so perplexing to so many? Perhaps, owing to our being conscious, we regard ourselves as experts on the matter, and it seems to us blindingly obvious that consciousness could not possibly be a brain state or process. We have a front-row seat, an unmediated first-hand awareness of what conscious experiences are like, and we know well-enough what brain processes are like. The two could not be more different. In the hands of philosophers, this sentiment is transmuted into the doctrine that consciousness cannot be identified with, or ‘reduced to’, anything physical. The reduction in question must be a relation among explanations, or predicates, not as it is sometimes cast, a relation among properties. What would it be to reduce something to something else? If the As are not reducible to the Bs, explanations of the As could not be derived from explanations of the Bs, nor could A-terms be analysed or paraphrased in a B-vocabulary.

Why does our confidence in the outré character of consciousness not extend to tables and trees? Take tables. We know what tables are like, and we know what physics reveals about their makeup. Individual tables are solid, coloured, smooth to the touch, but physics tells us that tables are, as Eddington put it, mostly empty space sparsely populated by colourless particles. Or tables might turn out to be perturbations in fields, thickenings in spacetime, or something stranger still. We are content to leave it to physics to discover the nature of whatever it is that makes assertions about individual tables true, thereby telling us what those tables are. Our inability to extract truths about tables from truths about particles or fields is unremarkable: tables are, in this regard, irreducible. What would be remarkable is someone’s insisting that from this it follows that tables could not possibly be clouds of particles or disturbances in fields, because tables obviously differ from such things. Claims to the effect that tables ‘arise’ or ‘emerge’ from clouds of particles or perturbations in fields, while more common, would be no less remarkable.

Why not think the same of consciousness? Why not think that neuroscience, and ultimately physics, might eventually reveal the nature of whatever makes particular ascriptions of consciousness true, what consciousness is?

Two shibboleths bar the way.

More here.

Anjuli Kolb reads “The Mustangs” by Natalie Diaz

NATALIE DIAZ, “The Mustangs” from Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb on Vimeo.

[Buy Natalie Diaz’s book Postcolonial Love Poem by clicking here.]

Thursday Poem

Migration

rows assemble in the bare elm above our house.

Restless, staring: like souls

who want back in life.

—And who wouldn’t want again

the hot bath after hard work,

with soft canyons of splitting foam;

or the glass of spring water

cold at the mouth?

To be startled by beauty—drops of bright

blood on the snow.

To be radiant.

All morning the crows watch me in the garden

putting in the early onions.

Their bodies look oiled.

Back in, back in,

they shake the wooden rattles.

by Jenny George

from the Academy of American Poets

Sean Carroll has a special Mindscape Podcast: Tara Smith on Coronavirus, Pandemics, and What We Can Do

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

This is a special episode of Mindscape, thrown together quickly. Many thanks to Tara Smith for joining me on short notice. Tara is an epidemiologist, and a great person to talk to about the novel coronavirus (and its associated disease, COVID-19) pandemic currently threatening the world. We talk about what viruses are, how they spread, and a lot of the science behind virology and pandemics. We also take a practical turn, talking about what measures (washing hands, social distancing, self-isolation) are useful at combating the spread of the virus, and which (wearing masks) are probably not. Then we look to the future, to ask what the endgame here is; Tara suggests that the kind of drastic measure we are currently putting up with might last a long time indeed.

This is a special episode of Mindscape, thrown together quickly. Many thanks to Tara Smith for joining me on short notice. Tara is an epidemiologist, and a great person to talk to about the novel coronavirus (and its associated disease, COVID-19) pandemic currently threatening the world. We talk about what viruses are, how they spread, and a lot of the science behind virology and pandemics. We also take a practical turn, talking about what measures (washing hands, social distancing, self-isolation) are useful at combating the spread of the virus, and which (wearing masks) are probably not. Then we look to the future, to ask what the endgame here is; Tara suggests that the kind of drastic measure we are currently putting up with might last a long time indeed.

More here.

Wednesday, March 18, 2020

Yuval Noah Harari: In the Battle Against Coronavirus, Humanity Lacks Leadership

Yuval Noah Harari in Time:

Many people blame the coronavirus epidemic on globalization, and say that the only way to prevent more such outbreaks is to de-globalize the world. Build walls, restrict travel, reduce trade. However, while short-term quarantine is essential to stop epidemics, long-term isolationism will lead to economic collapse without offering any real protection against infectious diseases. Just the opposite. The real antidote to epidemic is not segregation, but rather cooperation.

Epidemics killed millions of people long before the current age of globalization. In the 14th century there were no airplanes and cruise ships, and yet the Black Death spread from East Asia to Western Europe in little more than a decade. It killed between 75 million and 200 million people – more than a quarter of the population of Eurasia. In England, four out of ten people died. The city of Florence lost 50,000 of its 100,000 inhabitants.

In March 1520, a single smallpox carrier – Francisco de Eguía – landed in Mexico. At the time, Central America had no trains, buses or even donkeys. Yet by December a smallpox epidemic devastated the whole of Central America, killing according to some estimates up to a third of its population.

More here.

Social distancing is here to stay for much more than a few weeks

Gideon Lichfield in the MIT Technology Review:

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

We all want things to go back to normal quickly. But what most of us have probably not yet realized—yet will soon—is that things won’t go back to normal after a few weeks, or even a few months. Some things never will.

It’s now widely agreed (even by Britain, finally) that every country needs to “flatten the curve”: impose social distancing to slow the spread of the virus so that the number of people sick at once doesn’t cause the health-care system to collapse, as it is threatening to do in Italy right now. That means the pandemic needs to last, at a low level, until either enough people have had Covid-19 to leave most immune (assuming immunity lasts for years, which we don’t know) or there’s a vaccine.

How long would that take, and how draconian do social restrictions need to be? Yesterday President Donald Trump, announcing new guidelines such as a 10-person limit on gatherings, said that “with several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly.” In China, six weeks of lockdown are beginning to ease now that new cases have fallen to a trickle.

But it won’t end there. As long as someone in the world has the virus, breakouts can and will keep recurring without stringent controls to contain them.

More here.

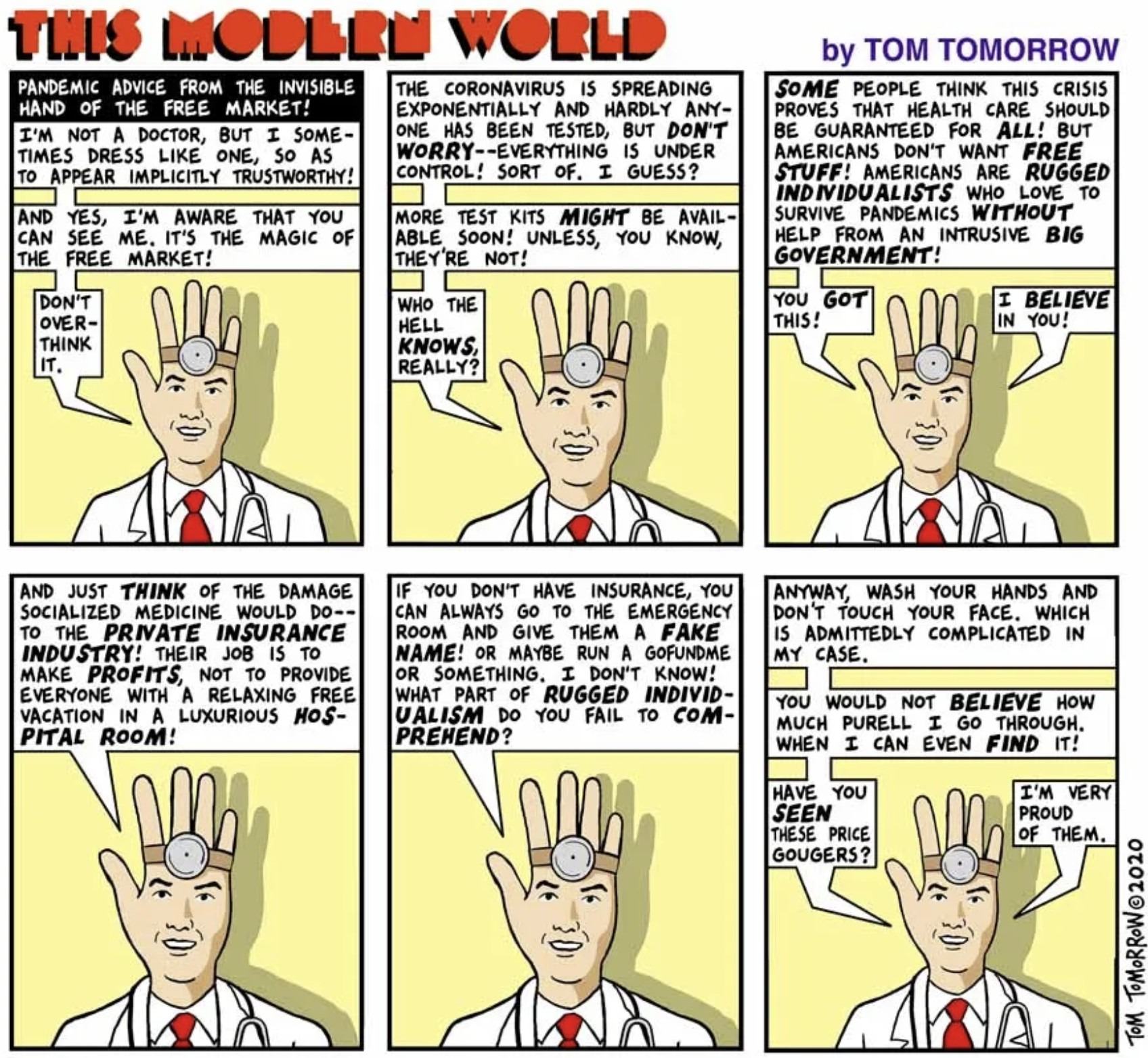

The Free Market Will Save Us From the Coronavirus!

An Optimist’s Case for COVID-19 Lockdown, Our Safest and Quickest Path Back to Normalcy

Jonathan Kay in Quillette:

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19—the acute respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus—a pandemic. And almost everywhere you look, the data appear to show a frightening exponential rise in new cases. As I write this, on March 17th, the latest available reports show that confirmed cases have doubled in Italy over the last five days. In Spain, the most recent doubling period has been just three days. In France, Germany, Switzerland, the United States, the UK, and Netherlands, the figures are four, three, three, five, three, and four respectively. When these facts are presented in graph form, the vertiginous lines suggest a world feverishly coughing its way into apocalypse.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19—the acute respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus—a pandemic. And almost everywhere you look, the data appear to show a frightening exponential rise in new cases. As I write this, on March 17th, the latest available reports show that confirmed cases have doubled in Italy over the last five days. In Spain, the most recent doubling period has been just three days. In France, Germany, Switzerland, the United States, the UK, and Netherlands, the figures are four, three, three, five, three, and four respectively. When these facts are presented in graph form, the vertiginous lines suggest a world feverishly coughing its way into apocalypse.

But assuming that governments act responsibly, and absent some horrifying SARS-CoV-2 mutation, there will be no apocalypse. Stock markets and economies will suffer greatly. But even this damage can be mitigated through decisive action. The more aggressively that our leaders act to suppress the spread of COVID-19, the more quickly the crisis will pass, and the sooner we will all be able to return to normal daily life. The decisions we make now could mean the difference between a global recession and a historical event on par with The Great Depression.

The good news is that we definitely can suppress COVID-19, even if no cure or effective vaccine emerges. We know this because it already has been done in the most populous country on Earth.

More here.

What Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks can teach us about peer review

Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

One of the best-known sketches from Monty Python’s Flying Circus features John Cleese as a bowler-hatted bureaucrat with the fictional Ministry of Silly Walks. It’s a classic of physical comedy, right up there with the troupe’s Dead Parrot sketch (“This parrot has ceased to be!”) in terms of cultural significance.

One of the best-known sketches from Monty Python’s Flying Circus features John Cleese as a bowler-hatted bureaucrat with the fictional Ministry of Silly Walks. It’s a classic of physical comedy, right up there with the troupe’s Dead Parrot sketch (“This parrot has ceased to be!”) in terms of cultural significance.

A pair of scientists at Dartmouth College [corrected] have performed a gait analysis of the various silly walks on display, publishing their findings in a new paper in the journal Gait and Posture. It’s intended in part as a commemoration on the 50-year anniversary of the sketch but also to draw attention to the need for a more streamlined peer review process for grants in the health sciences.

The two authors, Erin Butler and Nathaniel Dominy, are married, having met 12 years ago at Stanford. (Butler was a TA for a class where Dominy gave a lecture on the evolution of bipedalism.) Dominy is the Monty Python fan. “So, put together a Monty Python fan with a creative scientific mind and an expert in gait analysis, and this paper is what you get,” Butler told Ars. Or, as they wrote in their paper, “It really is the silliness of the sketch that resonates with us, and extreme silliness seems more relevant now than ever before in this increasingly Pythonesque world.”

More here.