Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

On Sunday, on Tuesday, and again on Wednesday, President Donald Trump accused the TV talk-show host Joe Scarborough of murder. On Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, he attacked the integrity of America’s forthcoming “rigged” election. When he woke up on Wednesday, he alleged that the Obama Administration had “spied, in an unprecedented manner, on the Trump Campaign, and beyond, and even on the United States Senate.” By midnight Wednesday, a few hours after the number of U.S. deaths in the coronavirus pandemic officially exceeded a hundred thousand, the President of the United States retweeted a video that says, “the only good Democrat is a dead Democrat.”

On Sunday, on Tuesday, and again on Wednesday, President Donald Trump accused the TV talk-show host Joe Scarborough of murder. On Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, he attacked the integrity of America’s forthcoming “rigged” election. When he woke up on Wednesday, he alleged that the Obama Administration had “spied, in an unprecedented manner, on the Trump Campaign, and beyond, and even on the United States Senate.” By midnight Wednesday, a few hours after the number of U.S. deaths in the coronavirus pandemic officially exceeded a hundred thousand, the President of the United States retweeted a video that says, “the only good Democrat is a dead Democrat.”

This is not the first time when the tweets emanating from the man in the White House have featured baseless accusations of murder, vote fraud, and his predecessor’s “illegality and corruption.” It’s not even the first time this month. So many of the things that Trump does and says are inconceivable for an American President, and yet he does and says them anyway. The Trump era has been a seemingly endless series of such moments. From the start of his Administration, his tweets have been an open-source intelligence boon, a window directly into the President’s needy id, and a real-time guide to his obsessions and intentions. Misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies were always central to his politics. In recent months, however, his tweeting appears to have taken an even darker, more manic, and more mendacious turn, as Trump struggles to manage the convergence of a massive public-health crisis and a simultaneous economic collapse while running for reëlection. He is tweeting more frequently, and more frantically, as events have closed in on him. Trailing in the polls and desperate to change the subject from the coronavirus, mid-pandemic Trump has a Twitter feed that is meaner, angrier, and more partisan than ever before, as he amplifies conspiracy theories about the “deep state” and media enemies such as Scarborough while seeking to exacerbate divisions in an already divided country.

Strikingly, this dark turn with the President’s tweets comes as he is using his Twitter feed as an even more potent vehicle for telling his Republican followers what to do—and they are listening.

More here.

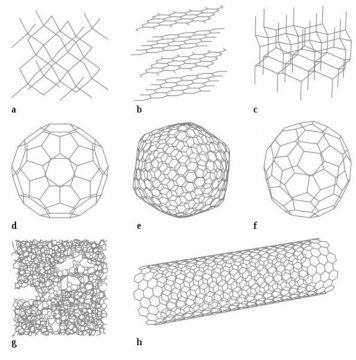

Emergence occurs when there is a conceptual discontinuity between two descriptions targeting the same phenomenon. This does not mean that emergence is a purely subjective phenomenon — only that scientific ‘double coverage’ may be a good place to look for emergent phenomena.

Emergence occurs when there is a conceptual discontinuity between two descriptions targeting the same phenomenon. This does not mean that emergence is a purely subjective phenomenon — only that scientific ‘double coverage’ may be a good place to look for emergent phenomena. Respiratory infections occur through the transmission of virus-containing droplets (>5 to 10 μm) and aerosols (≤5 μm) exhaled from infected individuals during breathing, speaking, coughing, and sneezing. Traditional respiratory disease control measures are designed to reduce transmission by droplets produced in the sneezes and coughs of infected individuals. However, a large proportion of the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears to be occurring through airborne transmission of aerosols produced by asymptomatic individuals during breathing and speaking (

Respiratory infections occur through the transmission of virus-containing droplets (>5 to 10 μm) and aerosols (≤5 μm) exhaled from infected individuals during breathing, speaking, coughing, and sneezing. Traditional respiratory disease control measures are designed to reduce transmission by droplets produced in the sneezes and coughs of infected individuals. However, a large proportion of the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears to be occurring through airborne transmission of aerosols produced by asymptomatic individuals during breathing and speaking ( The amazing thing about Faiz Ahmed Faiz is that you can never leave him behind. Witness how he emerged in the midst of the recent protests in India with ‘Hum Dekhenge’ being sung in half a dozen languages to the point where flummoxed authorities were forced to treat a man, dead for a good 35 years, as a threat to national security.

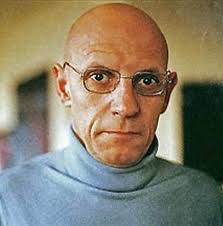

The amazing thing about Faiz Ahmed Faiz is that you can never leave him behind. Witness how he emerged in the midst of the recent protests in India with ‘Hum Dekhenge’ being sung in half a dozen languages to the point where flummoxed authorities were forced to treat a man, dead for a good 35 years, as a threat to national security. For his part, however, Foucault moved on, somewhat singularly among his generation. Rather than staying in the world of words, in the 1970s he shifted his philosophical attention to power, an idea that promises to help explain how words, or anything else for that matter, come to give things the order that they have. But Foucault’s lasting importance is not in his having found some new master-concept that can explain all the others. Power, in Foucault, is not another philosophical godhead. For Foucault’s most crucial claim about power is that we must refuse to treat it as philosophers have always treated their central concepts, namely as a unitary and homogenous thing that is so at home with itself that it can explain everything else.

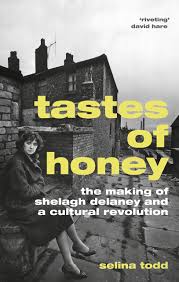

For his part, however, Foucault moved on, somewhat singularly among his generation. Rather than staying in the world of words, in the 1970s he shifted his philosophical attention to power, an idea that promises to help explain how words, or anything else for that matter, come to give things the order that they have. But Foucault’s lasting importance is not in his having found some new master-concept that can explain all the others. Power, in Foucault, is not another philosophical godhead. For Foucault’s most crucial claim about power is that we must refuse to treat it as philosophers have always treated their central concepts, namely as a unitary and homogenous thing that is so at home with itself that it can explain everything else. Selina Todd’s biography of Delaney does two things well. It helps us understand how someone the press insisted on calling a ‘Salford teenager’ was able to create this remarkable work – and it shows how hard the people who brought the play to stage and screen worked to shift the spotlight away from that intense mother-daughter dynamic. There was a script, too, for ‘new writers’ in the late 1950s and 1960s: they were to be young, authentic and, if possible, working class; they were to be masculine, rebellious and shocking. When, in April 1958, Delaney sent her play to Joan Littlewood, the director of the avant-garde Theatre Workshop in East London, she adopted a naive, Northern persona that was more than a little misleading. ‘A fortnight ago I didn’t know the theatre existed,’ she gushed to Littlewood – but then a friend had taken her to see a play and she had discovered ‘something that meant more to me than myself’. She now knew she wanted to write plays, and in two weeks had produced the enclosed ‘epic’. ‘Please can you help me? I’m willing enough to help myself.’ Christened plain ‘Sheila’, she signed the letter ‘Shelagh Delaney’, the name by which she would be known from then on.

Selina Todd’s biography of Delaney does two things well. It helps us understand how someone the press insisted on calling a ‘Salford teenager’ was able to create this remarkable work – and it shows how hard the people who brought the play to stage and screen worked to shift the spotlight away from that intense mother-daughter dynamic. There was a script, too, for ‘new writers’ in the late 1950s and 1960s: they were to be young, authentic and, if possible, working class; they were to be masculine, rebellious and shocking. When, in April 1958, Delaney sent her play to Joan Littlewood, the director of the avant-garde Theatre Workshop in East London, she adopted a naive, Northern persona that was more than a little misleading. ‘A fortnight ago I didn’t know the theatre existed,’ she gushed to Littlewood – but then a friend had taken her to see a play and she had discovered ‘something that meant more to me than myself’. She now knew she wanted to write plays, and in two weeks had produced the enclosed ‘epic’. ‘Please can you help me? I’m willing enough to help myself.’ Christened plain ‘Sheila’, she signed the letter ‘Shelagh Delaney’, the name by which she would be known from then on. On Sunday, on Tuesday, and again on Wednesday, President

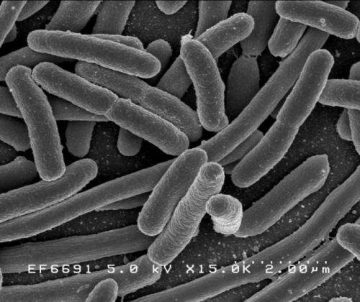

On Sunday, on Tuesday, and again on Wednesday, President  Bacteria have a cunning ability to survive in unfriendly environments. For example, through a complicated series of interactions, they can identify—and then build resistance to—

Bacteria have a cunning ability to survive in unfriendly environments. For example, through a complicated series of interactions, they can identify—and then build resistance to— There continues to be an impressive appetite for conceptual and philosophical explorations of psychiatry. The publishing field is now populated by a diverse array of backgrounds and perspectives. The general public seems mostly interested in decrying the medicalization of normal and the transformation of our woes into neatly packaged mental disorders. The academic literature is dominated by philosophers and philosophically-trained professionals; while the intellectual discourse is of high caliber, it unfortunately remains largely inaccessible to mental health professionals and much of the general public, and resultantly it has had little influence outside the academic community. There is also a cohort of individuals with a critical interest in the subject but whose philosophical focus remains stuck on classical critical figures such as Thomas Szasz, Michel Foucault and R.D. Laing, with little engagement with contemporary philosophy of science. The philosophical work of Kenneth Kendler and his various collaborators (John Campbell, Carl Craver, Kenneth Schaffner, Erik Engstrom, Rodrigo Munoz, George Murphy, and Peter Zachar) assembled in a specially curated volume occupies a unique and special position in this contemporary landscape and there is much to be said in its favor.

There continues to be an impressive appetite for conceptual and philosophical explorations of psychiatry. The publishing field is now populated by a diverse array of backgrounds and perspectives. The general public seems mostly interested in decrying the medicalization of normal and the transformation of our woes into neatly packaged mental disorders. The academic literature is dominated by philosophers and philosophically-trained professionals; while the intellectual discourse is of high caliber, it unfortunately remains largely inaccessible to mental health professionals and much of the general public, and resultantly it has had little influence outside the academic community. There is also a cohort of individuals with a critical interest in the subject but whose philosophical focus remains stuck on classical critical figures such as Thomas Szasz, Michel Foucault and R.D. Laing, with little engagement with contemporary philosophy of science. The philosophical work of Kenneth Kendler and his various collaborators (John Campbell, Carl Craver, Kenneth Schaffner, Erik Engstrom, Rodrigo Munoz, George Murphy, and Peter Zachar) assembled in a specially curated volume occupies a unique and special position in this contemporary landscape and there is much to be said in its favor.

What would become known as the CARES Act

What would become known as the CARES Act

Two incidents separated by twelve hours and twelve hundred miles have taken on the appearance of the control and the variable in a grotesque experiment about race in America. On Monday morning, in New York City’s Central Park, a white woman named Amy Cooper called 911 and told the dispatcher that an African-American man was threatening her. The man she was talking about, Christian Cooper, who is no relation, filmed the call on his phone. They were in the Ramble, a part of the park favored by bird-watchers, including Christian Cooper, and he had simply requested that she leash her dog—something that is required in the area. In the video, before making the call, Ms. Cooper warns Mr. Cooper that she is “going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.” Her needless inclusion of the race of the man she fears serves only to summon the ancient impulse to protect white womanhood from the threats posed by black men. For anyone with a long enough memory or a recent enough viewing of the series “

Two incidents separated by twelve hours and twelve hundred miles have taken on the appearance of the control and the variable in a grotesque experiment about race in America. On Monday morning, in New York City’s Central Park, a white woman named Amy Cooper called 911 and told the dispatcher that an African-American man was threatening her. The man she was talking about, Christian Cooper, who is no relation, filmed the call on his phone. They were in the Ramble, a part of the park favored by bird-watchers, including Christian Cooper, and he had simply requested that she leash her dog—something that is required in the area. In the video, before making the call, Ms. Cooper warns Mr. Cooper that she is “going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.” Her needless inclusion of the race of the man she fears serves only to summon the ancient impulse to protect white womanhood from the threats posed by black men. For anyone with a long enough memory or a recent enough viewing of the series “