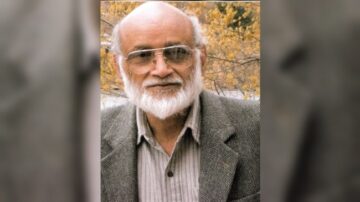

Mehr Farooqi in The Indian Express:

Last night, a friend called to give me the sad news of Naim sahib’s passing. He had not been too well since suffering a stroke a couple of years ago but after returning from rehab his spirit was as indomitable as ever. He relished writing and wrote with zest; sparkling essays, columns and a weekly, later monthly, newsletter that he dispatched electronically to a large following. Naim sahib did not shy away from technology. He had a website on which he posted stuff that he liked. But the newsletter was his commentary on various subjects related to literature, including world politics that impacted literature. He wrote what was on his mind without mincing the truth. It was a privilege to be on his mailing list.

Last night, a friend called to give me the sad news of Naim sahib’s passing. He had not been too well since suffering a stroke a couple of years ago but after returning from rehab his spirit was as indomitable as ever. He relished writing and wrote with zest; sparkling essays, columns and a weekly, later monthly, newsletter that he dispatched electronically to a large following. Naim sahib did not shy away from technology. He had a website on which he posted stuff that he liked. But the newsletter was his commentary on various subjects related to literature, including world politics that impacted literature. He wrote what was on his mind without mincing the truth. It was a privilege to be on his mailing list.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some people took up baking, others decided to get a dog; I chose to grow and observe slime mould. The study in my partner’s flat in Edinburgh became home to two cultures of Physarum polycephalum, an acellular slime mould sometimes more casually referred to as ‘the blob’.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some people took up baking, others decided to get a dog; I chose to grow and observe slime mould. The study in my partner’s flat in Edinburgh became home to two cultures of Physarum polycephalum, an acellular slime mould sometimes more casually referred to as ‘the blob’. When you accept that other people have secrets, and they will always have secrets, you are preparing yourself for a much more predictable, much more successful future. Because once you accept that reality, you can start applying behaviors, practices into your personal life, into your business life that make it so that you gain more secrets than you share. And gaining secrets in an economy of secrets is the same thing as gaining wealth or gaining power or gaining leverage. You can either live in a world that is not true and believe that people are honest, or you can live in a world that is factual and objective and recognize that all people are keeping secrets from you.

When you accept that other people have secrets, and they will always have secrets, you are preparing yourself for a much more predictable, much more successful future. Because once you accept that reality, you can start applying behaviors, practices into your personal life, into your business life that make it so that you gain more secrets than you share. And gaining secrets in an economy of secrets is the same thing as gaining wealth or gaining power or gaining leverage. You can either live in a world that is not true and believe that people are honest, or you can live in a world that is factual and objective and recognize that all people are keeping secrets from you. The Thinker just discovered, with a mix of awe and quiet dread, that ChatGPT—a machine—could write his latest policy memo better and faster than he could.

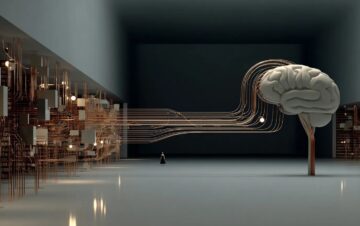

The Thinker just discovered, with a mix of awe and quiet dread, that ChatGPT—a machine—could write his latest policy memo better and faster than he could. I was born in the United States and therefore speak American English, because, aside from a brief few years in my childhood when my father assured me that my first language was Mandarin Chinese (my mother’s native tongue), I was raised in an English-speaking household.

I was born in the United States and therefore speak American English, because, aside from a brief few years in my childhood when my father assured me that my first language was Mandarin Chinese (my mother’s native tongue), I was raised in an English-speaking household. How far back must we go to understand the roots of the long enmity between Iran and the United States? A good place to start is the Iran Hostage Crisis, sparked forty-six years ago after the US ally, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, sought protection and medical care in the US. Iranian revolutionaries took over the US Embassy in Tehran in November 1979 and held sixty-six staffers, demanding the Shah’s return.

How far back must we go to understand the roots of the long enmity between Iran and the United States? A good place to start is the Iran Hostage Crisis, sparked forty-six years ago after the US ally, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, sought protection and medical care in the US. Iranian revolutionaries took over the US Embassy in Tehran in November 1979 and held sixty-six staffers, demanding the Shah’s return.

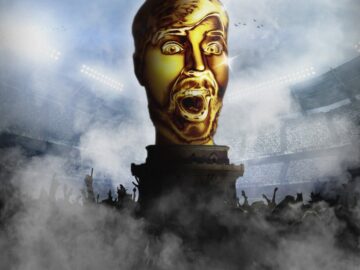

Jimmy Donaldson, the 27-year-old online content creator and entrepreneur known as MrBeast, is by any reasonable metric one of the most popular entertainers on the planet. His

Jimmy Donaldson, the 27-year-old online content creator and entrepreneur known as MrBeast, is by any reasonable metric one of the most popular entertainers on the planet. His  I increasingly find people asking me “does AI damage your brain?” It’s a revealing question. Not because AI causes literal brain damage (it doesn’t) but because the question itself shows how deeply we fear what AI might do to our ability to think. So, in this post, I want to discuss ways of using AI to help, rather than hurt, your mind. But why the obsession over AI damaging our brains?

I increasingly find people asking me “does AI damage your brain?” It’s a revealing question. Not because AI causes literal brain damage (it doesn’t) but because the question itself shows how deeply we fear what AI might do to our ability to think. So, in this post, I want to discuss ways of using AI to help, rather than hurt, your mind. But why the obsession over AI damaging our brains? “I

“I  George Slavich recalls the final hours he spent with his father. It was a laughter-packed day. His father even broke into the song ‘You Are My Sunshine’ over dinner. “His deep, booming, joyful voice filled the entire restaurant,” says Slavich. “I was semi-mortified, as always, while my daughter relished the serenade.”

George Slavich recalls the final hours he spent with his father. It was a laughter-packed day. His father even broke into the song ‘You Are My Sunshine’ over dinner. “His deep, booming, joyful voice filled the entire restaurant,” says Slavich. “I was semi-mortified, as always, while my daughter relished the serenade.”

Does anyone write love letters anymore? We send emails. Or worse, texts, emoji. Fast, short, disposable. Once, love letters were slow to make and slower to arrive. They were keepsakes, confessions, feelings made physical. They had form. They were a genre unto themselves: often florid, achingly raw, very private. I’ve written them. Maybe you have, too. Now they’ve all but vanished — and with them, a particular architecture of emotion.

Does anyone write love letters anymore? We send emails. Or worse, texts, emoji. Fast, short, disposable. Once, love letters were slow to make and slower to arrive. They were keepsakes, confessions, feelings made physical. They had form. They were a genre unto themselves: often florid, achingly raw, very private. I’ve written them. Maybe you have, too. Now they’ve all but vanished — and with them, a particular architecture of emotion.