Sally Adee in Nature:

Keith Krehbiel lived with Parkinson’s disease for nearly 25 years before agreeing to try a brain implant that might alleviate his symptoms. He had long been reluctant to submit to the surgery. “It was a big move,” he says. But by 2020, his symptoms had become so severe that he grudgingly agreed to go ahead.

Keith Krehbiel lived with Parkinson’s disease for nearly 25 years before agreeing to try a brain implant that might alleviate his symptoms. He had long been reluctant to submit to the surgery. “It was a big move,” he says. But by 2020, his symptoms had become so severe that he grudgingly agreed to go ahead.

Deep-brain stimulation involves inserting thin wires through two small holes in the skull into a region of the brain associated with movement. The hope is that by delivering electrical pulses to the region, the implant can normalize aberrant brain activity and reduce symptoms. Since the devices were first approved almost three decades ago, some 200,000 people have had them fitted to help calm the tremors and rigidity caused by Parkinson’s disease. But about 40,000 of those who received devices made after 2020 got them with a special feature that has largely not yet been turned on. The devices can read brain waves and then adapt and tailor the rhythm of their output, in much the same way as a pacemaker monitors and corrects the heart’s electrical rhythms, says Helen Bronte-Stewart, a neurologist at Stanford University in California.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Not long ago, Dr. Richard Menger, a neurosurgeon, was ready to operate on a 16-year-old with complex scoliosis. A team of doctors had spent months preparing for the surgery, consulting orthopedists and cardiologists, even printing a 3D model of the teen’s spine. The surgery was scheduled for a Friday when Menger got the news: the teen’s insurer, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama, had denied coverage of the surgery.

Not long ago, Dr. Richard Menger, a neurosurgeon, was ready to operate on a 16-year-old with complex scoliosis. A team of doctors had spent months preparing for the surgery, consulting orthopedists and cardiologists, even printing a 3D model of the teen’s spine. The surgery was scheduled for a Friday when Menger got the news: the teen’s insurer, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama, had denied coverage of the surgery. “It appears early life got trapped in a minima of metabolic efficiency. Everything on that planet is starving. Meaning they can’t run their brains for a full day-night cycle. So they just… turn themselves off. Their consciousness dies. Then they reboot with the same memories in the morning. Of course, the memories are integrated differently each time into an entirely new standing consciousness wave.”

“It appears early life got trapped in a minima of metabolic efficiency. Everything on that planet is starving. Meaning they can’t run their brains for a full day-night cycle. So they just… turn themselves off. Their consciousness dies. Then they reboot with the same memories in the morning. Of course, the memories are integrated differently each time into an entirely new standing consciousness wave.” Recently, I found myself pouring my heart out, not to a human, but to a chatbot named Wysa on my phone. It nodded – virtually – asked me how I was feeling and gently suggested trying breathing exercises.

Recently, I found myself pouring my heart out, not to a human, but to a chatbot named Wysa on my phone. It nodded – virtually – asked me how I was feeling and gently suggested trying breathing exercises. The Democratic Party is in crisis, and it goes far beyond the stereotypical “Dems in Disarray” headlines. The party’s popularity numbers are abysmal: a

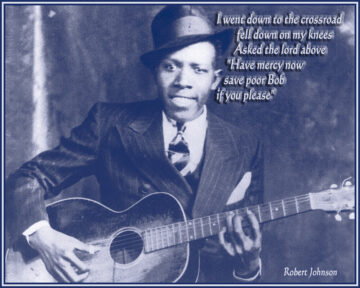

The Democratic Party is in crisis, and it goes far beyond the stereotypical “Dems in Disarray” headlines. The party’s popularity numbers are abysmal: a  As it emerged after the overthrow of Reconstruction, when black voices were again being silenced in public and civic spheres, the blues became an alternative form of communication. As Shelby “Poppa Jazz” Brown reminded the noted folklorist William Ferris,

As it emerged after the overthrow of Reconstruction, when black voices were again being silenced in public and civic spheres, the blues became an alternative form of communication. As Shelby “Poppa Jazz” Brown reminded the noted folklorist William Ferris, I

I In this wide-ranging interview, Paul Bloom explores how our best qualities, reason, morality, and compassion, can be paradoxically undercut by the very forces meant to protect them. Looking at his work on Perversity, he reveals the tightrope between chaos and autonomy, making human goodness not just aspirational but fragile, easily distorted, often misunderstood, and vulnerable to both logic and emotion when taken to extremes.

In this wide-ranging interview, Paul Bloom explores how our best qualities, reason, morality, and compassion, can be paradoxically undercut by the very forces meant to protect them. Looking at his work on Perversity, he reveals the tightrope between chaos and autonomy, making human goodness not just aspirational but fragile, easily distorted, often misunderstood, and vulnerable to both logic and emotion when taken to extremes. Purism was intended as a way of uniting the rigours of classicism with the modernity of the machine age. Flat planes of colour were combined with a highly symbolic visual language. Its most famous adherent was Fernand Léger. At the Ozenfant Academy, this slightly chilly left-brain philosophy of art existed alongside a dictatorial regime. Students were instructed in drawing with unforgiving hard pencils and giant sheets of paper, and encouraged towards exactness of line – sketching was a dirty word. They drew the same model, who held the same pose for two weeks. The actress Dulcie Gray, who attended the school, recalled that in the winter, the side of the model nearest the stove turned scarlet, while the other side was blue with cold. If the morning’s drawings passed muster, students were permitted to paint. A chart on the wall showed the colours they were allowed to use; the paint was to be applied according to an approved technique which yielded a consistent finish.

Purism was intended as a way of uniting the rigours of classicism with the modernity of the machine age. Flat planes of colour were combined with a highly symbolic visual language. Its most famous adherent was Fernand Léger. At the Ozenfant Academy, this slightly chilly left-brain philosophy of art existed alongside a dictatorial regime. Students were instructed in drawing with unforgiving hard pencils and giant sheets of paper, and encouraged towards exactness of line – sketching was a dirty word. They drew the same model, who held the same pose for two weeks. The actress Dulcie Gray, who attended the school, recalled that in the winter, the side of the model nearest the stove turned scarlet, while the other side was blue with cold. If the morning’s drawings passed muster, students were permitted to paint. A chart on the wall showed the colours they were allowed to use; the paint was to be applied according to an approved technique which yielded a consistent finish. We’d heard about the “€1 house” programme in which poor, depopulating towns put their abandoned or unused buildings up for sale. The programme, I soon learned, was actually a loose collection of schemes that economically struggling towns used to lure outside investment and new residents. The campaigns seemed to me to have been largely successful – some towns had sold all their listed properties. I pored over dozens of news articles that had served as €1 house promotion over the years. By attracting international buyers to a house that “costs less than a cup of coffee”, as one piece put it, some of Italy’s most remote towns now had new life circulating through them. Many local officials had come to see €1 house experiments as their potential salvation.

We’d heard about the “€1 house” programme in which poor, depopulating towns put their abandoned or unused buildings up for sale. The programme, I soon learned, was actually a loose collection of schemes that economically struggling towns used to lure outside investment and new residents. The campaigns seemed to me to have been largely successful – some towns had sold all their listed properties. I pored over dozens of news articles that had served as €1 house promotion over the years. By attracting international buyers to a house that “costs less than a cup of coffee”, as one piece put it, some of Italy’s most remote towns now had new life circulating through them. Many local officials had come to see €1 house experiments as their potential salvation. I began researching the lives of two 19th-century figures who have both been described as disinhibited. The first was a railroad construction foreman, Phineas Gage. The second was the photographer Eadweard Muybridge (born Edward Muggeridge in England). The two were contemporaries, and both lived in San Francisco for a time. Both were injured in accidents. But there the similarities end. Despite Muybridge’s brain injury being well documented and despite it transforming him, as some claim, in profound and disastrous ways, he scarcely features in the brain science literature, and his legacy remains predominantly that of an artistic and technical genius. Gage, by contrast, became famous for the outrageous behaviour that supposedly resulted from his injury. The literature paints him as a kind of avatar for behavioural dysfunction, with every other aspect of his life overshadowed by his status as disinhibition’s patient zero. Why are the legacies of these two ‘disinhibited’ people so different? I believe the answer tells us almost everything we need to know about the condition, about its origins and its continued use today.

I began researching the lives of two 19th-century figures who have both been described as disinhibited. The first was a railroad construction foreman, Phineas Gage. The second was the photographer Eadweard Muybridge (born Edward Muggeridge in England). The two were contemporaries, and both lived in San Francisco for a time. Both were injured in accidents. But there the similarities end. Despite Muybridge’s brain injury being well documented and despite it transforming him, as some claim, in profound and disastrous ways, he scarcely features in the brain science literature, and his legacy remains predominantly that of an artistic and technical genius. Gage, by contrast, became famous for the outrageous behaviour that supposedly resulted from his injury. The literature paints him as a kind of avatar for behavioural dysfunction, with every other aspect of his life overshadowed by his status as disinhibition’s patient zero. Why are the legacies of these two ‘disinhibited’ people so different? I believe the answer tells us almost everything we need to know about the condition, about its origins and its continued use today. America has

America has  “I suspect that the real moral thinkers end up, wherever they may start, in botany,” the essayist Annie Dillard mused in 1974. “We know nothing for certain, but we seem to see that the world turns upon growing.” The work of the British nature writer Richard Mabey is proof of Dillard’s wisdom. He has been thinking about botany since the 1970s, when he published “Food for Free,” his classic guide to edible plants, and his interest in vegetable life has always yielded a corresponding interest in human obligations. For him, botany is both a science and an ethics, and its primary tenet is that plants are — or ought to be — our equals.

“I suspect that the real moral thinkers end up, wherever they may start, in botany,” the essayist Annie Dillard mused in 1974. “We know nothing for certain, but we seem to see that the world turns upon growing.” The work of the British nature writer Richard Mabey is proof of Dillard’s wisdom. He has been thinking about botany since the 1970s, when he published “Food for Free,” his classic guide to edible plants, and his interest in vegetable life has always yielded a corresponding interest in human obligations. For him, botany is both a science and an ethics, and its primary tenet is that plants are — or ought to be — our equals. In the late summer of 1832, England was set aflame with wonder — a glimpse of something wild and flamboyant, shimmering with the lush firstness of a world untrammeled by the boot of civilization.

In the late summer of 1832, England was set aflame with wonder — a glimpse of something wild and flamboyant, shimmering with the lush firstness of a world untrammeled by the boot of civilization.