Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

One of the Supreme Court’s sharpest critics sits on it

Justin Jouvenal in The Washington Post:

“The majority’s ruling … is … profoundly dangerous, since it gives the Executive the go-ahead to sometimes wield the kind of unchecked, arbitrary power the Founders crafted our Constitution to eradicate,” Jackson wrote. Justice Amy Coney Barrett leveled an unusually personal retort in her majority opinion. “We will not dwell on Justice Jackson’s argument, which is at odds with more than two centuries’ worth of precedent, not to mention the Constitution itself,” Barrett wrote. “We observe only this: Justice Jackson decries an imperial Executive while embracing an imperial Judiciary.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The $100 Trillion Question: What Happens When AI Replaces Every Job?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rosalind Fox Solomon (1930 – 2025) Photographer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Even Though

A = pi r squared

even if a body

continues to fall

32 feet per second per second

which I hope

it will continue to do

nevertheless

after careful calculation

and by the grace of algebra

I am persuaded that

if truth is a number

not only is it never

in the back of the book

but it never comes out even

ends in a fraction

cannot be rounded off.

Approximation

was the first art.

It is the only science.

by John Stone

from In All This Rain

Louisiana State University Press, 1980

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, July 4, 2025

Our relationships, in five dimensions

Sam Dresser at Psyche:

I was intrigued to read about a proposed ‘unified framework’ for capturing how people see relationships. Researchers asked people from 19 world regions to rate the features of various types of relationships, ranging from siblings to leader and follower to fans of opposing sports teams. They found that relationships could be described in terms of five main dimensions:

I was intrigued to read about a proposed ‘unified framework’ for capturing how people see relationships. Researchers asked people from 19 world regions to rate the features of various types of relationships, ranging from siblings to leader and follower to fans of opposing sports teams. They found that relationships could be described in terms of five main dimensions:

- Formality: roughly, how formal and public a relationship is vs informal and private;

- Activeness: how close and involved vs distant;

- Valence: how friendly vs hostile;

- Exchange: how much it involves trading concrete resources like money vs intangible things like affection; and

- Equality: how equal each person’s power is in the relationship.

While the researchers say this model is ‘far from conclusive’, it does give scientists – and the rest of us – a new lens for considering our relationships and what they mean to us.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The résumé is dying, and AI is holding the smoking gun

Benj Edwards at Ars Technica:

Employers are drowning in AI-generated job applications, with LinkedIn now processing 11,000 submissions per minute—a 45 percent surge from last year, according to new data reported by The New York Times.

Employers are drowning in AI-generated job applications, with LinkedIn now processing 11,000 submissions per minute—a 45 percent surge from last year, according to new data reported by The New York Times.

Due to AI, the traditional hiring process has become overwhelmed with automated noise. It’s the résumé equivalent of AI slop—call it “hiring slop,” perhaps—that currently haunts social media and the web with sensational pictures and misleading information. The flood of ChatGPT-crafted résumés and bot-submitted applications has created an arms race between job seekers and employers, with both sides deploying increasingly sophisticated AI tools in a bot-versus-bot standoff that is quickly spiraling out of control.

The Times illustrates the scale of the problem with the story of an HR consultant named Katie Tanner, who was so inundated with over 1,200 applications for a single remote role that she had to remove the post entirely and was still sorting through the applications three months later.

In an age where ChatGPT can insert every keyword from a job description into a résumé with a simple prompt, her story is not unique.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Obviously True Theorem No One Can Prove

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Yascha Mounk: Reflections on my adoptive home this Fourth of July

Yascha Mounk at his own Substack:

A few months ago, on the New York subway, I looked up at the woman sitting opposite me, and found my eyes drawn to her cap: “I don’t give a F**K,” read big white letters stitched into navy blue cotton.

A few months ago, on the New York subway, I looked up at the woman sitting opposite me, and found my eyes drawn to her cap: “I don’t give a F**K,” read big white letters stitched into navy blue cotton.

Three million New Yorkers ride the subway every day. On some days, it feels as though a quarter of them have a stupid slogan of one kind or another embroidered on their caps. And yet, there was something about this particular woman, proudly sporting this particular slogan, that felt to me totemic of this particular moment in American life.

I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

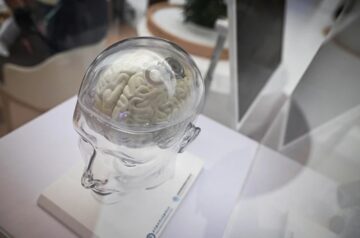

China pours money into brain chips that give paralysed people more control

Smiriti Malapaty in Nature:

A deep brain device that allowed a man with no limbs to play computer games is one of an increasing number of brain–computer interfaces (BCI) being trialled in people in China. The BCI system, developed by medical-technology company StairMed in Shanghai, China, is similar to the implants being trialled in people by Neuralink, owned by Elon Musk, based in Fremont, California. StairMed’s device has fewer probes than Neuralink’s device has, but is smaller and less invasive.

A deep brain device that allowed a man with no limbs to play computer games is one of an increasing number of brain–computer interfaces (BCI) being trialled in people in China. The BCI system, developed by medical-technology company StairMed in Shanghai, China, is similar to the implants being trialled in people by Neuralink, owned by Elon Musk, based in Fremont, California. StairMed’s device has fewer probes than Neuralink’s device has, but is smaller and less invasive.

Compared with the United States, China doesn’t have the long history in the field, and many of the devices being trialled there are simplified versions of those developed by US companies, say researchers. But “BCI research in China is developing very fast”, says Zhengwu Liu, an electrical engineer at the University of Hong Kong. Researchers in China are advancing the field on several fronts, such as by improving algorithms used to decode neural data and the implantation devices, says Christian Herff, a neural engineer at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, who co-organized a meeting on BCI in Shanghai last year.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Waymo’s Self-Driving Future Is Here

Andrew Chow in Time Magazine:

Moments before I hop into my first Waymo in Austin, Texas, the driverless car is already locked in a standoff with a human rival. I’ve hailed the car in a tricky triangular parking lot in the middle of a big intersection, hoping to hitch a ride downtown. After about six minutes of waiting, I see it approaching: a hulking white all-electric Jaguar SUV with whirring sensors on all sides, conjuring a rhinoceros with hummingbird wings. But when the Waymo enters the lot, it takes far too wide of a turn, and finds itself nose-to-nose with a pickup truck driver trying to exit. The driver glares at the Waymo, but sees nobody through the front windshield. For a second, man and machine face off in a very mundane version of The Terminator.

Moments before I hop into my first Waymo in Austin, Texas, the driverless car is already locked in a standoff with a human rival. I’ve hailed the car in a tricky triangular parking lot in the middle of a big intersection, hoping to hitch a ride downtown. After about six minutes of waiting, I see it approaching: a hulking white all-electric Jaguar SUV with whirring sensors on all sides, conjuring a rhinoceros with hummingbird wings. But when the Waymo enters the lot, it takes far too wide of a turn, and finds itself nose-to-nose with a pickup truck driver trying to exit. The driver glares at the Waymo, but sees nobody through the front windshield. For a second, man and machine face off in a very mundane version of The Terminator.

But then the pickup truck edges to the right, and the Waymo, sensing this, backs up slightly and pulls the opposite way, sliding cleanly past him and right up to where I’m standing, dumbfounded and relieved I haven’t caused a news incident. As I open the car door, a pleasant, corporate female voice greets me with a “Good to see you, Andrew.” I clamber in and put on my seatbelt, and the car merges cleanly out of the parking lot and into a future that, as the sci-fi author William Gibson once said, is already here—just not very evenly distributed.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Joyce Carol Oates Discusses Her New Novel, Fox

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

July 4th, 2025

Today is not a day for celebration.

Forget the fireworks.

To march down the center of Main

in party clothes under a soiled banner

singing “Joy To The World” would be

like showing up at a funeral

dressed to kill while warbling

a heavy-metal version of

Happy Days Are Here Again.

The burying of the Constitution

being nigh: the lights of the Capital

flickering out from the surge of

dark energy generated at a

hate-mill in the middle finger

of Florida, the red plow of a

tsunami of ignorance inundating

campuses of education, leveling

the hope of the young to be spared

from the likes of Genghis Khans,

This is not a time to party unless

you are in the retinue of a heartless

host whose idea of celebration is to

sit in Caesar’s chair in a coliseum

while lives of gladiators are

sacrificed to his whims of

hurt and blood.

A (now) Necessarily Anonymous American,

(Screw ICE)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Geological Sublime

Lewis Hyde at Harper’s Magazine:

Charles Darwin had no trouble discarding Adam and Eve, but that did not dispose of a problem he shared with Lyell: how to build a theory when a key element—the apparent infinity of time—defies comprehension. By my reading, several strategies arose. The first was to split infinity into tiny pieces, spans of time short enough to understand and work with. That is to say, Lyell and Darwin invented a kind of integral calculus, a method of adding together a series of infinitesimals, of minute changes that can, over “the lapse of ages,” produce huge consequences. Minute after minute, little waves hit a granite cliff, or year after year, the wings of pigeons vary slightly. Then, in the fullness of time, a wide pebble beach replaces the cliff, and a pigeon with an astounding fantail replaces its ancestor—or even, after an “accumulation of infinitesimally small inherited modifications” over “an almost infinite number of generations,” a bird appears that is not a pigeon at all but an entirely new species.

A second strategy begins with the obvious fact that the geological record has distinct periods. A cliff by the seashore reveals layers of limestone, sandstone, and cobbles, each presumably a distinct chapter in the history of the earth. If the years it took to write each chapter could be determined, then it would be easier to speak of those otherwise “very remote eras.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

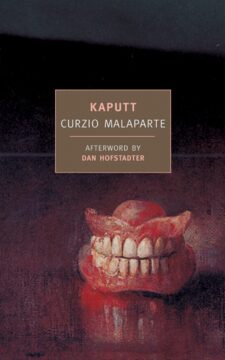

Curzio Malaparte’s Shock Tactics

Thomas Meaney at The New Yorker:

“You’re a born Fascist, one of the authentic ones,” the Italian writer Piero Gobetti wrote to his friend Curzio Malaparte in 1925, three years into Mussolini’s dictatorship. Gobetti, twenty-four and hailed as the most brilliant liberal writer of his generation, hoped to prevent Malaparte, then twenty-seven, from throwing all his talent behind the Fascist cause. “Don’t you understand that you’re wasting time, that the Fascists are playing you, that in the party you’re a fifth-class man, that your writings for the past year haven’t been worth a damn?” he wrote. Gobetti died the next year, from injuries inflicted by Black Shirts. Malaparte, by then, was making his name as one of Mussolini’s highbrow henchmen. During the Second World War, he became the regime’s star foreign correspondent, mobilizing the techniques of surrealism to evoke the era’s savagery. Malaparte rode to the Eastern Front with the Wehrmacht and toured the Warsaw ghetto with Nazi commanders and their wives. A fabulist whose medium was reality, he assembled his impressions into a nightmarish triptych—“The Volga Rises in Europe,” “Kaputt,” and “The Skin”—which forms the basis of his reputation today. With their uncanny sang-froid, their suave delight in ripping off the skin of experience, they leave no reader unmarked.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, July 3, 2025

“Dog” is a weird word

Colin Gorrie at Dead Language Society:

No, this is no hound. It’s just a dog.

No, this is no hound. It’s just a dog.

But somehow, this word dog — a word that wasn’t even dignified enough to write down once in the entire history of English writing before the eleventh century — would come to be the normal English word for man’s best friend, almost displacing the older form hound.

Stranger still, we don’t know for sure where the word dog came from.

We do have some theories, though. But I’ll need the help of some pigs, some frogs, and even some earwigs to explain.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Finding Peter Putnam

Amanda Gefter at Nautilus:

His name was Peter Putnam. He was a physicist who’d hung out with Albert Einstein, John Archibald Wheeler, and Niels Bohr, and two blocks from the crash, in his run-down apartment, where his partner, Claude, was startled by a screech, were thousands of typed pages containing a groundbreaking new theory of the mind.

His name was Peter Putnam. He was a physicist who’d hung out with Albert Einstein, John Archibald Wheeler, and Niels Bohr, and two blocks from the crash, in his run-down apartment, where his partner, Claude, was startled by a screech, were thousands of typed pages containing a groundbreaking new theory of the mind.

“Only two or three times in my life have I met thinkers with insights so far reaching, a breadth of vision so great, and a mind so keen as Putnam’s,” Wheeler said in 1991. And Wheeler, who coined the terms “black hole” and “wormhole,” had worked alongside some of the greatest minds in science.

Robert Works Fuller, a physicist and former president of Oberlin College, who worked closely with Putnam in the 1960s, told me in 2012, “Putnam really should be regarded as one of the great philosophers of the 20th century. Yet he’s completely unknown.”

That word—unknown—it came to haunt me as I spent the next 12 years trying to find out why.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The great friendship collapse: Inside The Anti-Social Century

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Georgist Roots of American Libertarianism

Reed Schwartz at Asterisk:

In 2023, Sam Altman embarked on a world tour, meeting with heads of state to discuss AI regulation. According to Time’s CEO of the Year Profile, he was also quietly promoting a more obscure cause — the ideas of the nineteenth-century political economist Henry George. As Altman explained in a 2021 blog post: If AI eventually automates most jobs, wealth will increasingly derive from the ownership of capital. To prevent runaway inequality, he proposed that the United States create a universal dividend, funded with taxes on large firms and — following George — the unimproved value of land.

In 2023, Sam Altman embarked on a world tour, meeting with heads of state to discuss AI regulation. According to Time’s CEO of the Year Profile, he was also quietly promoting a more obscure cause — the ideas of the nineteenth-century political economist Henry George. As Altman explained in a 2021 blog post: If AI eventually automates most jobs, wealth will increasingly derive from the ownership of capital. To prevent runaway inequality, he proposed that the United States create a universal dividend, funded with taxes on large firms and — following George — the unimproved value of land.

George has maintained a loyal (if marginal) following since his death in 1897. Today, he is rarely encountered outside of history of economics courses — and urbanist Twitter.1 But during the Gilded Age, he was one of the world’s foremost critics of inequality, and he is generally invoked in the same spirit today.

Notable, then, is the praise George has also received from Peter Thiel. How did an elitist libertarian come to favorably cite an egalitarian populist? The alignment is not unprecedented. Through a tradition that stretches from early Zionists at the turn of the 20th century to the Old Right in the interwar period and the first advocates for charter cities in the 1950s, the Georgist ideology persisted long after it was dropped by the American left. A libertarian turn to George is not a departure, but a homecoming.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Is Regret?

Max Lewis at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

If to err is human, then so too is to regret. At least if we follow Paddy McQueen in his recent book about the nature, normativity, and politics of regret. According to McQueen, regret is, roughly, a painful feeling of self-reproach or self-recrimination for making a “mistake” (21). Like all emotions, regret is more than just a judgment, though it has a constitutive thought type (i.e., “I have made a mistake”), which can be realized by many different token thoughts (e.g., “I wish I had not done that”, “I should have acted differently” or “what an idiot I am!”). Regret’s “phenomenological core” is the feeling of “kicking oneself” or “beating oneself up” for a mistake (21). Regret directs our attention to the mistake in decision-making we have made and motivates us to avoid making the same kind of mistake in the future (72, 136).

If to err is human, then so too is to regret. At least if we follow Paddy McQueen in his recent book about the nature, normativity, and politics of regret. According to McQueen, regret is, roughly, a painful feeling of self-reproach or self-recrimination for making a “mistake” (21). Like all emotions, regret is more than just a judgment, though it has a constitutive thought type (i.e., “I have made a mistake”), which can be realized by many different token thoughts (e.g., “I wish I had not done that”, “I should have acted differently” or “what an idiot I am!”). Regret’s “phenomenological core” is the feeling of “kicking oneself” or “beating oneself up” for a mistake (21). Regret directs our attention to the mistake in decision-making we have made and motivates us to avoid making the same kind of mistake in the future (72, 136).

What makes regret fitting (i.e., reasonable, rational, appropriate, or called for)?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dissenting — again — on the last day of the Supreme Court’s term, in its most high-profile case, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson did not mince words. She had for months plainly criticized the opinions of her conservative colleagues, trading the staid legalese typical of justices’ decisions for impassioned arguments against what she has described as their acquiescence to President Donald Trump. She returned to that theme again in the final case, ripping the court for limiting nationwide injunctions.

Dissenting — again — on the last day of the Supreme Court’s term, in its most high-profile case, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson did not mince words. She had for months plainly criticized the opinions of her conservative colleagues, trading the staid legalese typical of justices’ decisions for impassioned arguments against what she has described as their acquiescence to President Donald Trump. She returned to that theme again in the final case, ripping the court for limiting nationwide injunctions.