Matt Abrahams in Time Magazine:

Have you ever sat through a dull or inappropriate toast at a celebration, desperately wishing for it to end? You’re not alone. Bad toasts have a way of dragging down events, resulting in awkward silences, eye-rolling, and seat shifting. The problem with these subpar tributes is that they often make the audience uncomfortable, drag on and on, or focus too much on the speaker, rather than the individual or occasion being honored. Bad toasts can easily drain the energy from the room, detracting from the purpose of the celebration—to unite people in a moment of joy, respect, or reflection.

Have you ever sat through a dull or inappropriate toast at a celebration, desperately wishing for it to end? You’re not alone. Bad toasts have a way of dragging down events, resulting in awkward silences, eye-rolling, and seat shifting. The problem with these subpar tributes is that they often make the audience uncomfortable, drag on and on, or focus too much on the speaker, rather than the individual or occasion being honored. Bad toasts can easily drain the energy from the room, detracting from the purpose of the celebration—to unite people in a moment of joy, respect, or reflection.

Ultimately, giving a good toast can be a powerful and fulfilling experience, transforming a potentially awkward obligation into a heartfelt tribute. The secrets to success lie in reframing your approach, embracing a structured format, and keeping your focus on those being celebrated. The next time you find yourself standing in front of a group, ready to deliver a tribute, remember: it’s not about you—it’s about honoring the special moments that connect us all. So lift your glass, embrace the moment, and let your words be a gift that resonates with everyone present. By doing so, you not only create a beautiful memory for the honoree but also enrich the experience for everyone involved.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

IN 1946 THE AUSTRIAN WRITER Marlen Haushofer began publishing fairy tales and short stories in newspapers and small magazines. Her prewar writings—stories, poems, chapters of novels—had all been lost, and during the war she wrote “not a single line.” The new stories were a pragmatic measure: they were written to be published, to supplement the household budget. (Her husband, a provincial dentist, frittered the family’s finances away on flashy cars.) Yet since neither he nor her sons read her works, they could also be a form of revenge. “Professionally, I feed on anger,” she wrote to a friend in 1968, two years before her death. This stifled anger takes oblique forms. Philosophical novels, thrillers, dreams: her enervating allegories are like burrs—they stick.

IN 1946 THE AUSTRIAN WRITER Marlen Haushofer began publishing fairy tales and short stories in newspapers and small magazines. Her prewar writings—stories, poems, chapters of novels—had all been lost, and during the war she wrote “not a single line.” The new stories were a pragmatic measure: they were written to be published, to supplement the household budget. (Her husband, a provincial dentist, frittered the family’s finances away on flashy cars.) Yet since neither he nor her sons read her works, they could also be a form of revenge. “Professionally, I feed on anger,” she wrote to a friend in 1968, two years before her death. This stifled anger takes oblique forms. Philosophical novels, thrillers, dreams: her enervating allegories are like burrs—they stick. A coming-of-age ceremony, a Burmese bar mitzvah, a meditation retreat: I had called it all of those things to friends in the weeks before. It was a little bit of each but “more ceremonial slash familial than necessarily religious,” I’d qualified. We’d bargained with my mother for weeks to get out of it. We’re nearly thirty, my brother Nick reasoned. We’re adults. We didn’t want to shave our heads, wear monk’s robes, meditate all day. Maybe it is important to you, but we don’t care about religion, we said, armed with years of therapy.

A coming-of-age ceremony, a Burmese bar mitzvah, a meditation retreat: I had called it all of those things to friends in the weeks before. It was a little bit of each but “more ceremonial slash familial than necessarily religious,” I’d qualified. We’d bargained with my mother for weeks to get out of it. We’re nearly thirty, my brother Nick reasoned. We’re adults. We didn’t want to shave our heads, wear monk’s robes, meditate all day. Maybe it is important to you, but we don’t care about religion, we said, armed with years of therapy. In the Middle Ages, friendship was

In the Middle Ages, friendship was  Randomness is a source of power. From the coin toss that decides which team gets the ball to the random keys that secure online interactions, randomness lets us make choices that are fair and impossible to predict.

Randomness is a source of power. From the coin toss that decides which team gets the ball to the random keys that secure online interactions, randomness lets us make choices that are fair and impossible to predict.

There’s a quote I’m fond of, falsely attributed to Lenin, that “ethics are the aesthetics of the future.” It was in fact coined by Gorky, and as with so many misattributed phrases, it is also misquoted. I had always quietly reordered the line in my mind, preferring to have aesthetics in the first position, and when I finally went looking for it, and found it — in an essay Gorky wrote on Anatoly France — I was vindicated to discover that it actually read: “Aesthetics was [his] ethics — the ethics of the future.” That it’s thought to be authored by Lenin is perhaps understandable: it is a revolutionary sentiment after all, one that would have pleased the Romantics, the Surrealists, or any other radical avant-garde that aimed at transvaluation. It could also easily be, I think, the unofficial epigraph, the spiritual motto of Peter Weiss’s trilogy of novels, The Aesthetics of Resistance.

There’s a quote I’m fond of, falsely attributed to Lenin, that “ethics are the aesthetics of the future.” It was in fact coined by Gorky, and as with so many misattributed phrases, it is also misquoted. I had always quietly reordered the line in my mind, preferring to have aesthetics in the first position, and when I finally went looking for it, and found it — in an essay Gorky wrote on Anatoly France — I was vindicated to discover that it actually read: “Aesthetics was [his] ethics — the ethics of the future.” That it’s thought to be authored by Lenin is perhaps understandable: it is a revolutionary sentiment after all, one that would have pleased the Romantics, the Surrealists, or any other radical avant-garde that aimed at transvaluation. It could also easily be, I think, the unofficial epigraph, the spiritual motto of Peter Weiss’s trilogy of novels, The Aesthetics of Resistance. Most of us wouldn’t consider the Middle Ages the epitome of medical sophistication, thanks to our perception of their barbaric and (from a modern perspective) ridiculous strategies for helping the ill. But against all prejudices, medieval medicine was actually more advanced and science-based than we might think.

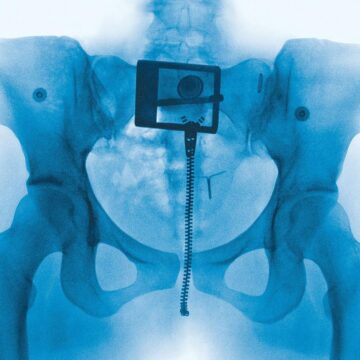

Most of us wouldn’t consider the Middle Ages the epitome of medical sophistication, thanks to our perception of their barbaric and (from a modern perspective) ridiculous strategies for helping the ill. But against all prejudices, medieval medicine was actually more advanced and science-based than we might think. On one side, advocates for legalised assisted dying invoke patients’ rights to make their own medical choices. Making it possible for doctors to assist their patients to die, they propose, allows us to avoid pointless suffering and to die ‘with dignity’. While assisted dying represents a departure from recent medical practice, it accords with values that the medical community holds dear, including compassion and beneficence.

On one side, advocates for legalised assisted dying invoke patients’ rights to make their own medical choices. Making it possible for doctors to assist their patients to die, they propose, allows us to avoid pointless suffering and to die ‘with dignity’. While assisted dying represents a departure from recent medical practice, it accords with values that the medical community holds dear, including compassion and beneficence. Researchers have been sneaking secret messages into their papers in an effort to trick artificial intelligence (AI) tools into giving them a positive peer-review report.

Researchers have been sneaking secret messages into their papers in an effort to trick artificial intelligence (AI) tools into giving them a positive peer-review report. The press cycle preceding Lorde’s new album, Virgin, was one of the most scrutinized of its kind in some time. She has been pressed, during junkets, for more information after saying she doesn’t feel like a man or woman. Fans, editors, and news aggregators gobble up the two or three throwaway lines published in short profiles in magazines like Rolling Stone, Vogue, and GQ. No one mentions the journalists soliciting these quotes—unless fans take them to task for portraying their idols in a negative light. Hero worship can easily obscure the dirt beneath the mythology of a pop star.

The press cycle preceding Lorde’s new album, Virgin, was one of the most scrutinized of its kind in some time. She has been pressed, during junkets, for more information after saying she doesn’t feel like a man or woman. Fans, editors, and news aggregators gobble up the two or three throwaway lines published in short profiles in magazines like Rolling Stone, Vogue, and GQ. No one mentions the journalists soliciting these quotes—unless fans take them to task for portraying their idols in a negative light. Hero worship can easily obscure the dirt beneath the mythology of a pop star. Around the world, governments are racing to build world-class universities. From Germany’s Exzellenzinitiative to India’s “Institutes of Eminence,” the goal is the same: to cultivate institutions that attract and nurture top global talent, conduct cutting-edge research, and drive innovation and growth. But the stakes are particularly high in the United States and China, given the escalating competition between the world’s two largest economies.

Around the world, governments are racing to build world-class universities. From Germany’s Exzellenzinitiative to India’s “Institutes of Eminence,” the goal is the same: to cultivate institutions that attract and nurture top global talent, conduct cutting-edge research, and drive innovation and growth. But the stakes are particularly high in the United States and China, given the escalating competition between the world’s two largest economies. My faith first wavers

My faith first wavers