Debbie Koenig in WebMD:

When Howard Wolinsky was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, he expected to kiss bagels goodbye — too many carbs. But a personalized diet based on his own gut microbiome offered a pleasant surprise: “It turns out those little bugs in my guts seem to like bread, if it’s combined with fats and proteins,” he says.

When Howard Wolinsky was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, he expected to kiss bagels goodbye — too many carbs. But a personalized diet based on his own gut microbiome offered a pleasant surprise: “It turns out those little bugs in my guts seem to like bread, if it’s combined with fats and proteins,” he says.

Wolinsky’s diet came from DayTwo, a company that uses research from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel to create customized advice for people with diabetes. From his home in suburban Chicago, Wolinsky, 71, sent the company a stool sample and a completed questionnaire, and he got back guidance about precisely which foods would spike his blood glucose and which would keep it steady. He was also taking an oral medication for his diabetes. “I could have a bagel, with cream cheese and lox,” he says. “That combination got a really good rating on the DayTwo scale.” He was amazed to find that when he followed DayTwo’s advice, his blood sugar remained within a normal range. It didn’t spike the way it would for foods outside their recommendations.

News Flash: Diets Aren’t One-Size-Fits-All

DayTwo has plenty of company in the personalized diet business. At least a dozen outfits offer nutrition advice customized to your body, based on DNA or blood tests, microbiome profiling, or a combination of those. Several promise weight loss, while others focus on specific conditions or just general “wellness.” Each uses its own proprietary process, and for some, the science behind it gets murky. Costs range from under $100 to nearly $1,000 for different services. DayTwo, for example, charges $499 for a microbiome testing kit, personalized app, orientation call with a registered dietitian, and microbiome summary report.

More here.

In her 2019 book, “

In her 2019 book, “ A man finds himself in Antwerp with nothing to do. Then he remembers, among other things, that this is the town where the painter Peter Paul Rubens made his home. At first, this annoys him, because he has no interest whatsoever in the painter. But then he thinks, why not write a book about Rubens.

A man finds himself in Antwerp with nothing to do. Then he remembers, among other things, that this is the town where the painter Peter Paul Rubens made his home. At first, this annoys him, because he has no interest whatsoever in the painter. But then he thinks, why not write a book about Rubens. Creativity is one of those things that we all admire but struggle to define or make concrete. Music provides a useful laboratory in which to examine what creativity is all about — how do people become creative, what is happening in their brains during the creative process, and what kinds of creativity does the audience actually enjoy? David Rosen and Scott Miles are both neuroscientists and musicians who have been investigating this question from the perspective of both listeners and performers. They have been performing neuroscientific experiments to understand how the brain becomes creative, and founded Secret Chord Laboratories to develop software that will predict what kinds of music people will like.

Creativity is one of those things that we all admire but struggle to define or make concrete. Music provides a useful laboratory in which to examine what creativity is all about — how do people become creative, what is happening in their brains during the creative process, and what kinds of creativity does the audience actually enjoy? David Rosen and Scott Miles are both neuroscientists and musicians who have been investigating this question from the perspective of both listeners and performers. They have been performing neuroscientific experiments to understand how the brain becomes creative, and founded Secret Chord Laboratories to develop software that will predict what kinds of music people will like.

As a boy in Brownsville and in Bed-Stuy, I was tormented by the question of protection, because, of course, I, too, wanted to be protected. Like any number of black boys in those neighborhoods, I grew up in a matrilineal society, where I had been taught the power—the necessity—of silence. But how could you not cry out when you couldn’t save your mother because you couldn’t defend yourself? Although I had this in common with other guys, something separated me from them when it came to joining those demonstrations, to leaping in the air when black bodies were threatened. My distance had to do with my queerness. The guys who took the chance to protect their families and themselves were the same guys who called me “faggot.”

As a boy in Brownsville and in Bed-Stuy, I was tormented by the question of protection, because, of course, I, too, wanted to be protected. Like any number of black boys in those neighborhoods, I grew up in a matrilineal society, where I had been taught the power—the necessity—of silence. But how could you not cry out when you couldn’t save your mother because you couldn’t defend yourself? Although I had this in common with other guys, something separated me from them when it came to joining those demonstrations, to leaping in the air when black bodies were threatened. My distance had to do with my queerness. The guys who took the chance to protect their families and themselves were the same guys who called me “faggot.” What is to be done with hope? Ali Smith is a great artist of possibility. Think of the role chance plays in her work, from The Accidental to How to be Both’s thrillingly shuffled structure that meant you had a fifty-fifty chance of getting the contemporary narrative first or the historical one. But these are bleak times – from Smith’s perspective, anyway, which I should state here is broadly my own too.

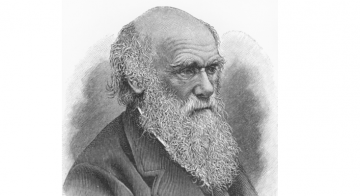

What is to be done with hope? Ali Smith is a great artist of possibility. Think of the role chance plays in her work, from The Accidental to How to be Both’s thrillingly shuffled structure that meant you had a fifty-fifty chance of getting the contemporary narrative first or the historical one. But these are bleak times – from Smith’s perspective, anyway, which I should state here is broadly my own too. Many historians have noted the intimate connection between the theory of natural selection and the ascendant political and economic views of the society in which Darwin was a well-placed member. The Victorian elite were committed to the idea that the unfettered competition of Adam Smith and David Ricardo’s free market would drive economic and social advancement. In Darwin’s theory, they found nature’s own reflection of the social system they favored. As J.M. Keynes put it, “The principle of the survival of the fittest could be regarded as a vast generalization of the Ricardian economics.”

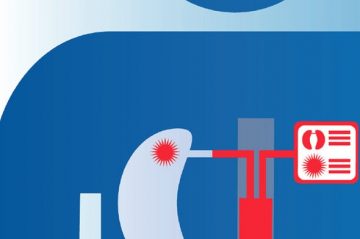

Many historians have noted the intimate connection between the theory of natural selection and the ascendant political and economic views of the society in which Darwin was a well-placed member. The Victorian elite were committed to the idea that the unfettered competition of Adam Smith and David Ricardo’s free market would drive economic and social advancement. In Darwin’s theory, they found nature’s own reflection of the social system they favored. As J.M. Keynes put it, “The principle of the survival of the fittest could be regarded as a vast generalization of the Ricardian economics.” A patient suspected of having cancer usually undergoes imaging and a biopsy. Samples of the tumor are excised, examined under a microscope and, often, analyzed to pinpoint the genetic mutations responsible for the malignancy. Together, this information helps to determine the type of cancer, how advanced it is and how best to treat it. Yet sometimes biopsies cannot be done, such as when a tumor is hard to reach. Obtaining and analyzing the tissue can also be expensive and slow. And because biopsies are invasive, they may cause infections or other complications.

A patient suspected of having cancer usually undergoes imaging and a biopsy. Samples of the tumor are excised, examined under a microscope and, often, analyzed to pinpoint the genetic mutations responsible for the malignancy. Together, this information helps to determine the type of cancer, how advanced it is and how best to treat it. Yet sometimes biopsies cannot be done, such as when a tumor is hard to reach. Obtaining and analyzing the tissue can also be expensive and slow. And because biopsies are invasive, they may cause infections or other complications. I was slightly nervous before my first meeting with the author Mirza Athar Baig, in the winter of 2017, at the Big M restaurant in Lahore’s Shadman Market. I had recently signed a book deal for my translation of his 2014 Urdu novel Hassan’s State of Affairs, and I was meeting him to discuss the first round of edits.

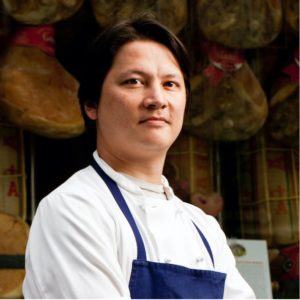

I was slightly nervous before my first meeting with the author Mirza Athar Baig, in the winter of 2017, at the Big M restaurant in Lahore’s Shadman Market. I had recently signed a book deal for my translation of his 2014 Urdu novel Hassan’s State of Affairs, and I was meeting him to discuss the first round of edits. Cooking is art, but it’s also very much science — mostly chemistry, but with important contributions from physics and biology. (Almost like a well-balanced recipe…) And I can’t think of anyone better to talk to about the intersection of these fields than Kenji López-Alt: professional chef and restauranteur, MIT graduate, and author of The Food Lab. We discuss how modern scientific ideas can improve your cooking, and more importantly, how to bring a scientific approach to cooking anything at all. Then we also get into the cultural and personal resonance of food, and offer a few practical tips.

Cooking is art, but it’s also very much science — mostly chemistry, but with important contributions from physics and biology. (Almost like a well-balanced recipe…) And I can’t think of anyone better to talk to about the intersection of these fields than Kenji López-Alt: professional chef and restauranteur, MIT graduate, and author of The Food Lab. We discuss how modern scientific ideas can improve your cooking, and more importantly, how to bring a scientific approach to cooking anything at all. Then we also get into the cultural and personal resonance of food, and offer a few practical tips.

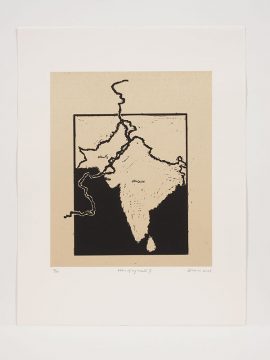

In a short video documentary produced by the Tate Modern in London, the artist talks about her exhibition, “Letters from Home,” which opened on 28 March 2013. Through personal letters, the exhibition illustrates an immigrant’s disconnection from his or her homeland. In the

In a short video documentary produced by the Tate Modern in London, the artist talks about her exhibition, “Letters from Home,” which opened on 28 March 2013. Through personal letters, the exhibition illustrates an immigrant’s disconnection from his or her homeland. In the  The real saga of the Statue of Liberty—the symbolic face of America around the world, and the backdrop of New York’s dazzling Fourth of July fireworks show—is an obscure piece of U.S. history. It had nothing to do with immigration. The telltale clue is the chain under Lady Liberty’s feet: she is stomping on it. “In the early sketches, she was also holding chains in her hand,”

The real saga of the Statue of Liberty—the symbolic face of America around the world, and the backdrop of New York’s dazzling Fourth of July fireworks show—is an obscure piece of U.S. history. It had nothing to do with immigration. The telltale clue is the chain under Lady Liberty’s feet: she is stomping on it. “In the early sketches, she was also holding chains in her hand,”