Category: Recommended Reading

Bent Fabric (1924 – 2020)

Onward, Christian Cowboys

Matt Hanson in The Baffler:

THE LATE, GREAT COMEDIAN Bill Hicks liked to tell a story about how audiences responded to his brand of scathing, gleefully subversive comedy, which he once referred to as “Chomsky with dick jokes.” Hicks’s relentless skewering of American materialism, jingoism, and religious hypocrisy didn’t exactly endear him to the mainstream. An appearance on the Letterman show was infamously cut—it was taped, but not aired—for containing jokes about pro-lifers, who were among the show’s sponsors. After a set in Tennessee, the story goes, a couple of locals confronted the Texas-born comic and declared that they were Christians and they didn’t like his act. Without missing a beat, Hicks responded with “well then, forgive me.” Instead, they broke his arm.

THE LATE, GREAT COMEDIAN Bill Hicks liked to tell a story about how audiences responded to his brand of scathing, gleefully subversive comedy, which he once referred to as “Chomsky with dick jokes.” Hicks’s relentless skewering of American materialism, jingoism, and religious hypocrisy didn’t exactly endear him to the mainstream. An appearance on the Letterman show was infamously cut—it was taped, but not aired—for containing jokes about pro-lifers, who were among the show’s sponsors. After a set in Tennessee, the story goes, a couple of locals confronted the Texas-born comic and declared that they were Christians and they didn’t like his act. Without missing a beat, Hicks responded with “well then, forgive me.” Instead, they broke his arm.

You might think reacting in such a spirit of vengeance is pretty much the exact opposite of how any self-professed Christian is supposed to behave. Yet there were deeper and more distinctly American pathologies at work: the guys who supposedly beat up Hicks were responding politically, not theologically. It wasn’t an attempt to defend Jesus’ honor or the tenets of whatever church they might have belonged to—it was to show that little punk who was really boss. They probably didn’t even notice the irony; and why would they? They may have grown up in an evangelical culture, but that culture glorifies what we now refer to as toxic masculinity. This “muscular Christianity” encourages both aggression and victimhood, emboldening believers, especially men, to impose their collective will on the rest of the public whenever they suddenly feel empowered or aggrieved.

In Jesus & John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted A Faith and Fractured a Nation the historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez explores this moral schizophrenia. We know there are legions of people on the religious right who talk a good game about following Christ but end up voting overwhelmingly for venal, crass, blustering wannabe tough guys like the current president and his enablers in Congress. But much of the evangelical leadership is this way, too. It often consists of self-appointed alpha male types who write bestselling books with imposing titles like Dare to Discipline, and Never Surrender, and You: The Warrior Leader, and Why We [meaning Muslims, of course] Want to Kill You. A writer for the Christian Broadcasting Network even teamed up with a Baptist minister a couple of years ago to produce The Faith of Donald J. Trump: A Spiritual Biography. While trying to mimic the terse, stoic cowboy ideal of manhood nicked from old Western movies, these opportunistic showboats often end up sounding and acting a lot more like Tom Cruise’s Frank T.J. Mackie in Magnolia, the brash misogynist who gives conferences about how to seduce and destroy women and who turns out to be a basket case of Oedipal rage and self-loathing.

The use of John Wayne as an evangelical role model implicitly suggests how some people’s religious beliefs are akin to identifying with their favorite movie stars.

More here.

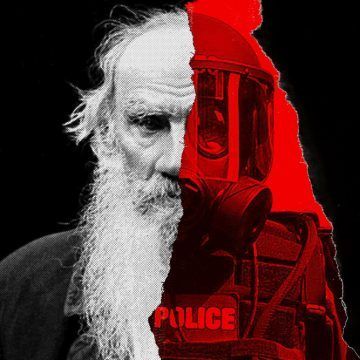

Leo Tolstoy vs. the Police

Jennifer Wilson in The New York Times:

Tolstoy was drawn to seekers, to characters perpetually in the throes of spiritual crisis; George Orwell described them as figures “struggling to make their souls.” Indeed, Tolstoy saw emergencies, personal and social, as necessary ruptures that could spark a deeper questioning of society and the beliefs that supported it. Of his own spiritual reawakening, captured in his memoir “A Confession” (1882), he described feeling as though the ground beneath him had collapsed. It is no wonder, then, that readers are finding new urgency in his work at a time when the racial and economic inequities revealed by Covid-19 and police killings have inspired unprecedented numbers of people to begin questioning some of this country’s foundational myths. With calls to defund the police, many are asking, for the first time in their lives, not just how our institutions function but whether they should exist at all.

Tolstoy was drawn to seekers, to characters perpetually in the throes of spiritual crisis; George Orwell described them as figures “struggling to make their souls.” Indeed, Tolstoy saw emergencies, personal and social, as necessary ruptures that could spark a deeper questioning of society and the beliefs that supported it. Of his own spiritual reawakening, captured in his memoir “A Confession” (1882), he described feeling as though the ground beneath him had collapsed. It is no wonder, then, that readers are finding new urgency in his work at a time when the racial and economic inequities revealed by Covid-19 and police killings have inspired unprecedented numbers of people to begin questioning some of this country’s foundational myths. With calls to defund the police, many are asking, for the first time in their lives, not just how our institutions function but whether they should exist at all.

One of Tolstoy’s seekers who found himself on such a path is Ivan Vassilievich, the protagonist of his 1903 short story “After the Ball.” Ivan is a young society man who falls in love with the daughter of a colonel, and plans to enlist himself until a fateful early-morning walk. He has spent the previous night at a ball in town, dancing with the daughter, a “bony” young beauty named Varenka: “Though I was a fancier of champagne,” he reflects, “I did not drink, because, without any wine, I was drunk with love.” However, Ivan falls as much in love with Varenka’s father, a kind and gentle-seeming man, who, Ivan tenderly notes, wears plain boots to the ball because he prefers to spend all his extra money on his daughter. After the ball, Ivan returns home, but is still so full of enchantment that he cannot sleep.

Instead, he takes a walk across the snowy streets in the direction of Varenka’s home, but when he arrives, he encounters a confounding scene: “Soldiers in black uniforms were standing in two rows facing each other, holding their guns at their sides and not moving. Behind them stood the drummer and fifer, ceaselessly repeating the same unpleasant, shrill melody.” It is a military gantlet and the accused, a young Tatar officer (Tatars were an ethnic minority in Russia), is being punished for desertion. Ivan looks on, frozen, as the young man’s body becomes bloodied: “His whole body jerking, his feet splashing through the melting snow, the punished man moved toward me under a shower of blows.” Ivan sees that the colonel leading the procession is none other than Varenka’s father, the man he thought of only hours before as loving and warm.

More here.

Saturday, August 1, 2020

Rules of the Game?

Lorna Finlayson in the New Left Review:

Lorna Finlayson in the New Left Review:

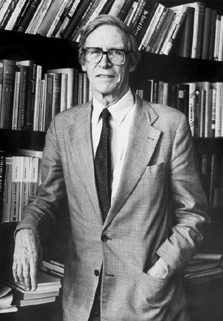

Katrina Forrester’s In the Shadow of Justice approaches Rawls’s work from the perspective of an intellectual historian. Her central thesis is that Rawls should be seen not as a philosopher of the 1960s—the era of Vietnam and of Lyndon Johnson’s ‘Great Society’—but rather as a thinker of the America of the 1940s and 50s. In those years, liberals sceptical of the interventionism of the administrative state saw their task as that of ‘securing the values of freedom and equality without the state intervention and political control that decades of state expansion had made a new norm’. On his return to Princeton in 1946 after three years’ combat in the Pacific War, the young Rawls embraced a ‘barebones’ anti-statism, close to that of Hayek or Walter Lippmann. In particular, Forrester demonstrates the importance for him of Frank Knight’s Ethics of Competition (1935): Rawls underlined his personal copy in three different pens and drew from the work of Knight and others the key idea of the game and its consensual rules as a social model. From Lippmann’s The Good Society (1937) he borrowed the analogy of the highway code—consensual regulation of the flow of traffic benefited all drivers, regardless of where they were going—widely used by early ordo- and neo-liberals. The heuristic device of the discussion between ‘reasonable men’—‘average, rational, right-thinking and fair’ heads of households—was already present in his 1949 doctoral thesis on ethical knowledge.

More here.

Bugs Rule

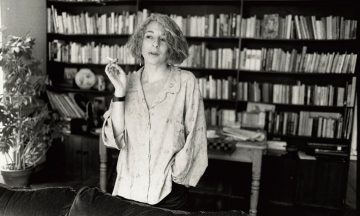

‘Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told?’ by Jenny Diski

Kate Kellaway at The Guardian:

In her introduction, Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the LRB, writes: “One of the pleasures of reading Jenny Diski, especially the essays, is that pleasure is such a large part of it.” Diski was worth hiring on any subject: feed her base metal, she turned it into gold. When not writing about herself, she is at her best considering the nasty and/or nondescript. Her subjects include Jeffrey Dahmer, Howard Hughes and Richard Branson, and she does not let Christine Keeler get away with a stuffy, faux-respectable take on her past. It is only because she has forced her way through “every damn word” of Keith Richards’s coarsely self-serving autobiography (in which he reveals Mick Jagger has a “tiny todger”) that she is determined to go ahead with her review. She is the most undeceived of writers – and surprising. Who else would combine reviewing a biography of Denis Thatcher with a reading of Melville’s Moby-Dick?

In her introduction, Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the LRB, writes: “One of the pleasures of reading Jenny Diski, especially the essays, is that pleasure is such a large part of it.” Diski was worth hiring on any subject: feed her base metal, she turned it into gold. When not writing about herself, she is at her best considering the nasty and/or nondescript. Her subjects include Jeffrey Dahmer, Howard Hughes and Richard Branson, and she does not let Christine Keeler get away with a stuffy, faux-respectable take on her past. It is only because she has forced her way through “every damn word” of Keith Richards’s coarsely self-serving autobiography (in which he reveals Mick Jagger has a “tiny todger”) that she is determined to go ahead with her review. She is the most undeceived of writers – and surprising. Who else would combine reviewing a biography of Denis Thatcher with a reading of Melville’s Moby-Dick?

more here.

Climate Change’s New Ally: Big Finance

Madison Condon in Boston Review:

Madison Condon in Boston Review:

Over the past two years a striking change has taken place in the boardrooms of greenhouse-gas producers: a growing number of large companies have announced commitments to achieve “net zero” emissions by 2050. These include the oil majors BP, Shell, and Total, the mining giant Rio Tinto, and the electricity supplier Southern Company. While such commitments are often described as “voluntary”—not mandated by government regulation—they were often adopted begrudgingly by executives and boards acquiescing to demands made by a coordinated group of their largest shareholders.

This group, Climate Action 100+, is an association of many of the world’s largest institutional investors. With over 450 members, it manages a staggering $40 trillion in assets—roughly 46 percent of global GDP. Founded in 2017, the coalition initially was made up mostly of pension funds and European asset managers, but its ranks have grown rapidly, and last winter both J.P. Morgan and BlackRock (the world’s largest asset manager) became signatories to the association’s pledge to pressure portfolio companies to reduce emissions and disclose financial risks related to climate change.

Some critics think corporate “net zero” goals smack of greenwashing. That is a legitimate concern, but many of the latest commitments contain details that suggest they are more than just PR moves. Shareholders have pressed for tying executive compensation directly to the achievement of emissions goals. And some companies have begun to write down billions of dollars of fossil assets they previously claimed would be profitably sold. Emissions targets are not the only change investors are fighting for, either; they have been paying increasing attention to corporations’ efforts to thwart carbon regulation.

More here.

Remote working—an inflection point?

Christy Hoffman and Sharan Burrow in Social Europe:

Christy Hoffman and Sharan Burrow in Social Europe:

In the years to come, we may look back at 2020 as an inflection point—a pivotal moment when large numbers of workers began to reorganise their lives away from a worksite, towards new models of working at or near home. The global pandemic forced a sudden, disruptive shift in work, supported by technology which quickly adapted to make continued activity possible on a larger scale than ever imagined. Many predict that we shall never go back to the workplaces of the past.

Such teleworking has been gradually increasing for several decades, typically associated with jobs that are easily measurable and highly autonomous, often involving high levels of independent judgement. It has been most prevalent in northern Europe and, in the United States, in areas with long commute times and highly-priced office space, where both the employer and employee are incentivised to adopt the model.

But the pandemic has proved that a much wider range of work can be effectively performed away from a worksite, including work which is less skilled and autonomous. In fact, during the lockdown an estimated 40 per cent of all workers in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development were able to continue to work from home.

More here.

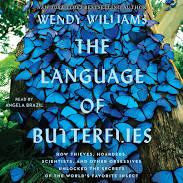

The Language of Butterflies

In her glorious and exuberant celebration of these biological flying machines, “The Language of Butterflies,” Wendy Williams takes us on a humorous and beautifully crafted journey that explores both the nature of these curious and highly intelligent insects and the eccentric individuals who coveted them.

more here.

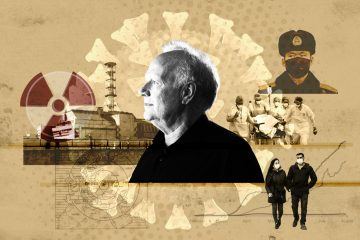

The Sociologist Who Could Save Us From Coronavirus

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

When COVID-19 struck, we wondered whether it might be Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Chernobyl. But after initial prevarication driven by Wuhan’s local politics, China’s national leadership reasserted its grip. The worst moment was Feb. 7, when hundreds of millions of Chinese took to the Internet to protest the treatment of whistleblowing doctor Li Wenliang, who had died of the disease. Since then Beijing has taken control, both of the disease and the media narrative. Far from being a perestroika moment, the noose of party discipline and censorship has tightened.

By the spring it was White House staffers who were likely watching the HBO miniseries Chernobyl and wondering about their own boss. Lately, the historian Harold James has asked whether the United States is living through its late-Soviet moment, with COVID-19 as President Donald Trump’s terminal crisis. But if that turns out to be the case, it will not be because of a botched cover-up; Americans are living neither in late-Soviet Ukraine nor in the era of Watergate, when a sordid exposé could sink a president. Of course, Trump was culpably irresponsible in making light of the disease. But he did so in the full glare of TV cameras. The president reveled in flouting the recommendations of eggheaded public health experts, correctly calculating that a large swath of his base was not concerned with conventional norms of truth or reason.

But the fact that neither Xi’s China nor Trump’s United States are a good match for the late Soviet Union doesn’t mean that Chernobyl is not relevant to our COVID-19 predicament.

More here.

Ashoka’s moral empire

Sonam Kachru in Aeon:

Sonam Kachru in Aeon:

In the Khyber valley of Northern Pakistan, three large boulders sit atop a hill commanding a beautiful prospect of the city of Mansehra. A low brick wall surrounds these boulders; a simple roof, mounted on four brick pillars, protects the rock faces from wind and rain. This structure preserves for posterity the words inscribed there: ‘Doing good is hard – Even beginning to do good is hard.’

The words are those of Ashoka Maurya, an Indian emperor who, from 268 to 234 BCE, ruled one of the largest and most cosmopolitan empires in South Asia. These words come from the opening lines of the fifth of 14 of Ashoka’s so-called ‘major rock edicts’, a remarkable anthology of texts, circa 257 BCE, in which Ashoka announced a visionary ethical project. Though the rock faces have eroded in Mansehra and the inscriptions there are now almost illegible, Ashoka’s message can be found on rock across the Indian subcontinent – all along the frontiers of his empire, from Pakistan to South India.

The message was no more restricted to a particular language than it was to a single place. Anthologised and inscribed across his vast empire onto freestanding boulders, dressed stone slabs and, beginning in 243 BCE, on monumental stone pillars, Ashoka’s ethical message was refined and rendered in a number of Indian vernaculars, as well as Greek and Aramaic. It was a vision intended to inspire people of different religions, from different regions, and across generations.

More here.

Why the Working Class Votes Against Its Economic Interests

Jeff Madrick in The New York Times:

One of the mysteries in politics for decades now has been why white working-class Americans began to vote Republican in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s. After all, it was Democrats who supported labor unions, higher minimum wages, expanded unemployment insurance, Medicare and generous Social Security, helping to lift workers into the middle class. Of course, an alternative economic view, led by economists like Milton Friedman, was that this turn toward the Republican Party was rational and served workers’ interests. He emphasized free markets, entrepreneurialism and the maximization of profit. These, Friedman argued, would raise wages for many and even most Americans.

One of the mysteries in politics for decades now has been why white working-class Americans began to vote Republican in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s. After all, it was Democrats who supported labor unions, higher minimum wages, expanded unemployment insurance, Medicare and generous Social Security, helping to lift workers into the middle class. Of course, an alternative economic view, led by economists like Milton Friedman, was that this turn toward the Republican Party was rational and served workers’ interests. He emphasized free markets, entrepreneurialism and the maximization of profit. These, Friedman argued, would raise wages for many and even most Americans.

But wages did not rise. And yet many in the working class kept voting Republican, still seemingly angered by Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, which was dedicated to helping the poor and assuring equal rights for people of color. In the 1980s, under Ronald Reagan, income inequality began to rise sharply; wages for typical Americans stagnated and poverty and homelessness increased. Capital investment remained relatively weak despite deep tax cuts (as it does today under Donald Trump). At the same time, antitrust regulation was severely wounded, and giant corporations began to monopolize industry after industry.

In 2004, Thomas Frank’s book “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” tried to explain why a once Democratic state had turned resolutely Republican. His eloquent review of the rhetoric of the age was instructive. But the presidential election of 2016 sent the sharpest message yet. Working-class voters in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin opted for Trump, and apparently against their economic interests. Trump had succeeded in appealing to their anger and the Democrats were caught flat-footed.

More here.

The Chaotic Design of Trump’s Mail-In-Voting Rants

Sue Halpern in The New Yorker:

On Thursday, when Donald Trump casually suggested on Twitter that the November election be delayed because “Universal Mail-In Voting” would make it “the most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT Election in history,” he was either setting the stage to contest the outcome or to explain away his impending defeat, or both. As the President should know by now, in-person voting during the coronavirus pandemic is dangerous, especially for older Americans and those with underlying health conditions. Yet he and his chorus of enablers have made a habit of trash-talking voting by mail, claiming, erroneously, that it promotes fraud. It’s no accident that Trump’s tweet specifically assailed “Universal Mail-In Voting,” since the word “universal” is triggering for anyone who is afraid of the will of the people.

On Thursday, when Donald Trump casually suggested on Twitter that the November election be delayed because “Universal Mail-In Voting” would make it “the most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT Election in history,” he was either setting the stage to contest the outcome or to explain away his impending defeat, or both. As the President should know by now, in-person voting during the coronavirus pandemic is dangerous, especially for older Americans and those with underlying health conditions. Yet he and his chorus of enablers have made a habit of trash-talking voting by mail, claiming, erroneously, that it promotes fraud. It’s no accident that Trump’s tweet specifically assailed “Universal Mail-In Voting,” since the word “universal” is triggering for anyone who is afraid of the will of the people.

So far, only five states have nearly universal mail-in balloting. For most of them, it took years of legislative wrangling before it was adopted, and years of preparation before it was deployed. Additionally, thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have no-excuse absentee balloting (meaning that anyone can request an absentee ballot for any reason). And every state has the infrastructure to enable military and overseas voters to cast ballots from afar. (Inexplicably, according to Thursday’s tweet, Trump believes that absentee ballots are good and mail-in ballots are bad, even though they are the same thing.) All told, nearly eighty per cent of the electorate would be able to vote by mail in November.

Past primaries have offered a preview of the problems that can arise when significant numbers of voters choose this option. (Hint: the issue isn’t voter fraud.) Take California, a blue state, where over four million people voted by mail in February of 2008. The deluge was so great that election officials were still counting ballots weeks after the election. (One unexpected wrinkle: they had to iron thousands of ballots that had gotten crumpled in the mail, before they could feed them into the tabulator.) In New Jersey, another blue state, some voters found their ballots returned to them (and thus not counted) because the Postal Service scanned the wrong addresses; other citizens received hastily assembled ballots with the wrong slate of candidates. In New York City, where more than four hundred thousand ballots were cast by mail in the June primary, election officials do not expect to have a final vote tally for some jurisdictions until August. A hundred thousand have already been invalidated, some because they arrived too late, others because they weren’t signed or had a signature that didn’t match the signature on file.

These are some of the typical, non-malicious, ways that voters may find themselves disenfranchised.

More here.

Friday, July 31, 2020

Disinformed to Death

Jonathan Freedland in the New York Review of Books:

When a pandemic is raging, it becomes harder to deny that rigorous, truthful information is a mortal necessity. No one need explain the risks of false information when one can point to, say, the likely consequences of Americans’ coming to believe they can deflect the virus by injecting themselves with bleach. (The fact that that advice came from the podium of the president of the United States is one we shall return to.) In Britain, Conservative ministers who once cheerfully brushed aside Brexit naysayers by declaring that the country had “had enough of experts” soon sought to reassure voters that they were “following the science.” In the first phase of the crisis, they rarely dared appear in public unless flanked by those they now gratefully referred to as experts.

So perhaps the moment is ripe for a trio of new books on disinformation. All three were written before the virus struck, before we saw people refuse to take life-saving action because they’d absorbed a baseless conspiracy theory linking Covid to, say, the towers that emit signals for 5G mobile phone coverage. But the pandemic might mean these books will now find a more receptive audience, one that has seen all too starkly that information is a resource essential for public health and well-being—and that our information supply is being deliberately, constantly, and severely contaminated.

More here.

Lady Liberty and other AI-generated portraits

More here.

Finding the Timeless and the Universal in Naiyer Masud’s Short Stories

Isabel Huacuja Alonso in The Caravan (from 2017):

“Destitutes Compound,” a story by Naiyer Masud, is about a young man who leaves his home after an argument with his father. After his only friend dies, the man concludes that it is time for him to return to his family. As he makes preparations for his homecoming, he realises that the children he met when he first arrived at the compound now have greying hair. When he returns, he learns that both his parents have passed away, but an old, blind grandmother still sits in the house’s entrance cracking betel nuts, just as she had when he left. The image of the grandmother rhythmically cracking betel nuts has stayed with me for years. To me, she symbolises time itself, resting still, awaiting our return.

“Destitutes Compound,” a story by Naiyer Masud, is about a young man who leaves his home after an argument with his father. After his only friend dies, the man concludes that it is time for him to return to his family. As he makes preparations for his homecoming, he realises that the children he met when he first arrived at the compound now have greying hair. When he returns, he learns that both his parents have passed away, but an old, blind grandmother still sits in the house’s entrance cracking betel nuts, just as she had when he left. The image of the grandmother rhythmically cracking betel nuts has stayed with me for years. To me, she symbolises time itself, resting still, awaiting our return.

Masud is the author of four acclaimed collections of short stories in Urdu. Most of his stories meticulously detail everyday feelings and sensations, but in ways that render them unfamiliar, uncomfortable and new. The narrator of “Ba’i’s Mourners” is consumed by a fear of brides when he learns of one who died from a scorpion bite before reaching her groom’s house. In “Obscure Domains of Fear and Desire,” the narrator describes the complex sensations that old houses evoke in him—some sections of them make him feel afraid, while others evoke an eerie expectation that a distant desire will soon be fulfilled.

More here.

Auden: “Doggerel by a Senior Citizen”

What Auden Believed

David Yezzi at The New Criterion:

A second spur for Auden was his experience during the Spanish Civil War, where he witnessed the destruction of churches and the persecution and murder of the clergy. As Carpenter writes, “In all, several thousand clergy members of religious orders fell victim to Republican persecutors, and this was only a fraction of the total number of people murdered on the Republican side.” Auden was deeply disillusioned by what he found in Spain. He later said that he “could not escape acknowledging that, however I had consciously ignored and rejected the Church for sixteen years, the existence of churches and what went on in them had all the time been very important to me.”

A second spur for Auden was his experience during the Spanish Civil War, where he witnessed the destruction of churches and the persecution and murder of the clergy. As Carpenter writes, “In all, several thousand clergy members of religious orders fell victim to Republican persecutors, and this was only a fraction of the total number of people murdered on the Republican side.” Auden was deeply disillusioned by what he found in Spain. He later said that he “could not escape acknowledging that, however I had consciously ignored and rejected the Church for sixteen years, the existence of churches and what went on in them had all the time been very important to me.”

Indeed, churchgoing again became very important to him. At one point, when Auden was living on Middagh Street in Brooklyn, Golo Mann notes, “On Sundays, he began to disappear for a couple of hours and returned with a look of happiness on his face. After a few weeks he confided in me the object of these mysterious excursions: the Episcopalian Church.”

more here.

The Unusual Life of a Nineteenth-Century Japanese Woman

Lesley Downer at the TLS:

So what was life like in that untouched Japan? We know a surprising amount about life in those days, in part because this was a highly literate society that kept and preserved copious records. Amy Stanley, an associate professor of history at Northwestern University, Illinois, is fluent in pre-modern as well as modern Japanese. In Stranger in the Shogun’s City, she uses private letters together with temple records, bills, receipts, tax returns, salary chits, legal and other documents and books of and about the times to piece together a marvellous patchwork of life in the decades before Western ships were sighted and interaction with the outside world began again in earnest. At the heart of Stanley’s book is the extraordinary and terrible story of Tsuneno, whose life went against the grain not only of what was expected of women in her day but also of what we assume life was like for women at that time.

more here.

For many, insects are an annoyance and at best an inconvenience. They deserve and even demand to be dispatched to an abrupt and untimely demise. In Victorian England, on the other hand, insects were so revered that documenting and cataloguing them became a popular and passionate pastime. The eccentric banker Charles Rothschild is said to have stopped a train to allow his servants to capture a rare species of butterfly that he had spotted from a window. His daughter Miriam Rothschild, in between determining the mechanism by which fleas jump and establishing a dragonfly reserve on her estate, became a leading authority on the monarch butterfly, which she described as “the most interesting insect in the world.”

For many, insects are an annoyance and at best an inconvenience. They deserve and even demand to be dispatched to an abrupt and untimely demise. In Victorian England, on the other hand, insects were so revered that documenting and cataloguing them became a popular and passionate pastime. The eccentric banker Charles Rothschild is said to have stopped a train to allow his servants to capture a rare species of butterfly that he had spotted from a window. His daughter Miriam Rothschild, in between determining the mechanism by which fleas jump and establishing a dragonfly reserve on her estate, became a leading authority on the monarch butterfly, which she described as “the most interesting insect in the world.”