Stacy Schiff in The New York Times:

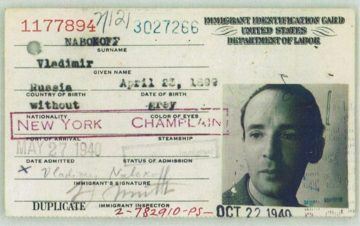

Amid frantic, last-minute negotiations, under a spray of machine-gun fire, Vladimir Nabokov fled Russia 100 years ago this week. His family had sought refuge from the Bolsheviks in the Crimean peninsula; those forces now made a vicious descent from the north. The chaos on the pier at Sebastopol could not match the scene that met the last of the Russian imperial family, evacuated the same week: In Yalta, terrified families mobbed a quay littered with abandoned cars. Nor were the Nabokovs’ accommodations as good. The Romanovs made their escape on a British man-of-war. The Nabokovs crowded into a filthy Greek cargo ship. Overrun by refugees, Constantinople turned them away. For several days they lurched about on a rough sea, subsisting on dog biscuits, sleeping on benches. Only the family jewelry traveled comfortably, nestled in a tin of talcum powder. On his 20th birthday, Nabokov disembarked finally in Athens. He would never again set eyes on Russia.

Amid frantic, last-minute negotiations, under a spray of machine-gun fire, Vladimir Nabokov fled Russia 100 years ago this week. His family had sought refuge from the Bolsheviks in the Crimean peninsula; those forces now made a vicious descent from the north. The chaos on the pier at Sebastopol could not match the scene that met the last of the Russian imperial family, evacuated the same week: In Yalta, terrified families mobbed a quay littered with abandoned cars. Nor were the Nabokovs’ accommodations as good. The Romanovs made their escape on a British man-of-war. The Nabokovs crowded into a filthy Greek cargo ship. Overrun by refugees, Constantinople turned them away. For several days they lurched about on a rough sea, subsisting on dog biscuits, sleeping on benches. Only the family jewelry traveled comfortably, nestled in a tin of talcum powder. On his 20th birthday, Nabokov disembarked finally in Athens. He would never again set eyes on Russia.

At the time of the evacuation he had spent 16 quiet months in the Crimea, the last speck of Russia in White hands. Already the Bolsheviks had murdered any number of harmless people; Nabokov’s jurist father, as his son would later note, was anything but harmless. In February 1917 riots had delivered a revolution. The czar abdicated, replaced by a liberal government, swept into power on a tide of popular support. Nabokov’s father, Vladimir Dmitrievich, played a prominent role in that administration. Months afterward Lenin returned from exile, disembarking at St. Petersburg’s Finland Station. Within the year, what had begun as an idealistic, progressive uprising would end — like Iran’s, like Egypt’s — in totalitarianism. With Lenin arrived another 20th-century staple: a one-party system in which hacks and henchmen replaced the competent and qualified.

The terror began immediately.

More here.