Category: Recommended Reading

The Presidential Town Halls Were Mister Rogers Versus Nasty Uncle Trump

Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

Even Donald Trump has moments of self-awareness. During an interview last week with Rush Limbaugh, the right-wing talk-radio host whom he honored with the Medal of Freedom earlier this year, the President briefly abandoned his puffery to admit that he might be defeated—and that his own nastiness would be the reason why. “Maybe I’ll lose,” he told Limbaugh, “because they’ll say I’m not a nice person.” He added, “I think I am a nice person,” before pivoting back to his trademark name-calling. A few days later, the political liability of his brutish persona was clearly on Trump’s mind again. “Can I ask you to do me a favor?” he begged “suburban women” at a rally in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, on Monday. “Will you please like me, please, please?”

Even Donald Trump has moments of self-awareness. During an interview last week with Rush Limbaugh, the right-wing talk-radio host whom he honored with the Medal of Freedom earlier this year, the President briefly abandoned his puffery to admit that he might be defeated—and that his own nastiness would be the reason why. “Maybe I’ll lose,” he told Limbaugh, “because they’ll say I’m not a nice person.” He added, “I think I am a nice person,” before pivoting back to his trademark name-calling. A few days later, the political liability of his brutish persona was clearly on Trump’s mind again. “Can I ask you to do me a favor?” he begged “suburban women” at a rally in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, on Monday. “Will you please like me, please, please?”

I do not know who will win the election less than three weeks from now. But I do know this: if Trump does lose, he’s right that his sheer unlikability will be a major contributing factor. He’s a bully and a boor. He’s overbearing, self-absorbed, impossible to shut up, and especially patronizing to women, which, of course, is one of the reasons why those suburban moms he is begging to vote for him are telling pollsters that they are decidedly against him.

More here.

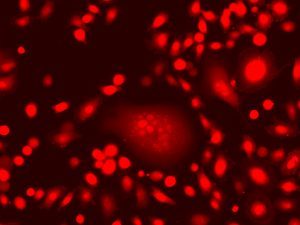

The adaptive cancer cell

From Outreach:

Species adapt to survive in a changing environment through the process of evolution. Evolutionary processes can also take place at the cellular level. Dr Sarah Amend of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA, is investigating poly-aneuploid cancer cells (PACCs). These large, DNA-laden cells, which are more common in metastatic cancer, develop evolvability: the capacity to evolve. Dr Amend believes that targeting the evolvability of PACCs and exploiting cancer ecology could offer new potential treatment routes for patients with metastatic cancer. When a person dies from cancer, the cause is usually not the primary tumour, but the metastases. Metastases are secondary tumours that develop when cancerous cells leave the original tumour and travel to other parts of the body. Despite many recent advances in medical science, metastases are extremely difficult to treat. While people with metastatic cancer can sometimes survive for many months or years, the disease is almost always fatal, leading to the deaths of 10 million cancer patients globally every year.

Species adapt to survive in a changing environment through the process of evolution. Evolutionary processes can also take place at the cellular level. Dr Sarah Amend of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA, is investigating poly-aneuploid cancer cells (PACCs). These large, DNA-laden cells, which are more common in metastatic cancer, develop evolvability: the capacity to evolve. Dr Amend believes that targeting the evolvability of PACCs and exploiting cancer ecology could offer new potential treatment routes for patients with metastatic cancer. When a person dies from cancer, the cause is usually not the primary tumour, but the metastases. Metastases are secondary tumours that develop when cancerous cells leave the original tumour and travel to other parts of the body. Despite many recent advances in medical science, metastases are extremely difficult to treat. While people with metastatic cancer can sometimes survive for many months or years, the disease is almost always fatal, leading to the deaths of 10 million cancer patients globally every year.

New research avenues are needed to address the challenges of preventing and treating metastatic cancer. One novel idea is to apply the principles of evolution to cancer. While, for many people, the term ‘evolution’ might conjure up images of larger species – humans evolving from ape-like creatures, for example – the tenets of evolutionary biology also apply on a cellular level. Normally, cells do not simply operate on their own behalf; each cell has a specific function, which contributes to the survival of the whole organism. However, sometimes things go wrong. Unwanted genetic changes can create a cancerous cell, one that divides uncontrollably, leading to the growth of a tumour. Dr Sarah Amend, Assistant Professor of Urology and Oncology at Johns Hopkins University, and her colleagues believe that cancers might undergo convergent evolution – the process in which the same characteristics emerge in different species as a result of separate evolutionary processes. For example, both birds and bats have wings, but the feature arose as the result of separate evolutionary processes.

One type of cancer cell, called a poly-aneuploid cancer cell (PACC), could potentially represent a form of convergent evolution. These cells appear to be present in every type of cancer, in all patients with metastatic disease; they appear to be the ‘common denominator’ of all types of cancer. If this holds true, then the majority of lethal tumours converge on a single phenotype of lethality and resistance: one the research team thinks is due to PACCs.

More here.

Sara Cwyner: Soft Film

The Trouble with Disparity

Adolph Reed and Walter Ben Michaels at nonsite:

In fact, not only will a focus on the effort to eliminate racial disparities not take us in the direction of a more equal society, it isn’t even the best way of eliminating racial disparities themselves. If the objective is to eliminate black poverty rather than simply to benefit the upper classes, we believe the diagnosis of racism is wrong, and the cure of antiracism won’t work. Racism is real and antiracism is both admirable and necessary, but extant racism isn’t what principally produces our inequality and antiracism won’t eliminate it. And because racism is not the principal source of inequality today, antiracism functions more as a misdirection that justifies inequality than a strategy for eliminating it.

In fact, not only will a focus on the effort to eliminate racial disparities not take us in the direction of a more equal society, it isn’t even the best way of eliminating racial disparities themselves. If the objective is to eliminate black poverty rather than simply to benefit the upper classes, we believe the diagnosis of racism is wrong, and the cure of antiracism won’t work. Racism is real and antiracism is both admirable and necessary, but extant racism isn’t what principally produces our inequality and antiracism won’t eliminate it. And because racism is not the principal source of inequality today, antiracism functions more as a misdirection that justifies inequality than a strategy for eliminating it.

What makes racism look like the problem? The very real racial disparities visible in American life. And what makes antiracism look like the solution? Two plausible but false beliefs: that racial disparities can in fact be eliminated by antiracism and that, if they could be, their elimination would make the U.S. a more equal society. The racial wealth gap, because it is so striking and commonly invoked, is a very good, not to say perfect, illustration of how, in our view, both the problem and solution are wrongly conceived.

more here.

Year 30: Germany’s Second Chance

Jürgen Habermas at Eurozine:

Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months – in Brussels and in Berlin too.

Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months – in Brussels and in Berlin too.

At first glance it might seem a bit far-fetched to compare the overcoming of a world order divided into two opposing camps and the global spread of victorious capitalism with the elemental nature of a pandemic that caught us off-guard and the related global economic crisis happening on an unprecedented scale. Yet if we Europeans can find a constructive response to the shock, this might provide a parallel between the two world-shattering events.

more here.

A new history charts the global legacy of Fordist mass production, tracing its appeal to political formations on both the left and the right

Justin H. Vassallo in the Boston Review:

The utopian ideal of globalization has imploded over the past decade. Rising demand in Western countries for greater state control over the economy reflects a range of grievances, from a chronic shortage of well-compensated work to a sense of national decline. In the United States, the dearth of domestic supply chains exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has only heightened alarm over the acute infrastructural weaknesses decades of outsourced production have created. Post-industrial society, rather than an advanced stage of shared affluence, is not only more unequal but fundamentally insecure. Rich but increasingly oligarchic countries are experiencing what we might call, following scholars of democratization, a dramatic “de-consolidation” of development.

The utopian ideal of globalization has imploded over the past decade. Rising demand in Western countries for greater state control over the economy reflects a range of grievances, from a chronic shortage of well-compensated work to a sense of national decline. In the United States, the dearth of domestic supply chains exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has only heightened alarm over the acute infrastructural weaknesses decades of outsourced production have created. Post-industrial society, rather than an advanced stage of shared affluence, is not only more unequal but fundamentally insecure. Rich but increasingly oligarchic countries are experiencing what we might call, following scholars of democratization, a dramatic “de-consolidation” of development.

To reverse this decline, political forces on both the left and the right are converging on the imperative to use industrial policy—the strategic process by which governments, either through state support of industrialists or state-owned enterprises, build up and diversify domestic manufacturing.

More here.

Friday Poem

Another Life

Women spend the afternoon squatting on the porch,

picking lice from each other’s hair.

They spend the evening feeding the little ones,

lulling them to sleep in the glow of the bottle lamp.

The rest of the night they offer their back to be slapped

and kicked by the men of the house

or sprawl half-naked on the hard wooden cot.

Crows and women greet the dawn together,

the women blowing into the oven to start the fire,

tapping on the back of the winnowing tray with five fingers

and, with two, picking out the stones.

Half their lives women pick stones from the rice.

All their lives stones pile up in their hearts,

no one there to touch them even with two fingers.

by Taslima Nasrin

from The Poetry Nook

Thursday, October 15, 2020

What Was California?

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

In 1879 Josiah Royce wrote a letter from Berkeley, to William James at Harvard, describing the intellectual condition of his home state: “There is no philosophy in California. From Siskiyou to Ft. Yuma, and from the Golden Gate to the summit of the Sierras there could not be found brains enough to accomplish the formation of a single respectable idea that was not manifest plagiarism.” From any other author, these words could only be received as complaint, but Royce himself understands them as a neutral description of fact, perhaps even as subtle praise for a land he deems ill-disposed to the convection of metaphysical hot air.

In 1879 Josiah Royce wrote a letter from Berkeley, to William James at Harvard, describing the intellectual condition of his home state: “There is no philosophy in California. From Siskiyou to Ft. Yuma, and from the Golden Gate to the summit of the Sierras there could not be found brains enough to accomplish the formation of a single respectable idea that was not manifest plagiarism.” From any other author, these words could only be received as complaint, but Royce himself understands them as a neutral description of fact, perhaps even as subtle praise for a land he deems ill-disposed to the convection of metaphysical hot air.

Faced with such a dilemma, between philosophy and California, Royce chose California. He stuck around the newly founded department of philosophy at Berkeley, but the longer he stayed away from Harvard, the more his own thoughts turned to the singular facts and contingent truths —generally held to be beneath the radar of philosophy, a discipline of the mind dedicated to general principles and necessary truths— of California history.

In 1886 he published a peculiar book entitled California: A Study of American Character. From the Conquest in 1846 to the Second Vigilance Committee in San Francisco. There would be a great deal to say about the title alone. How many people today know, for example, that early San Francisco’s lawless “Barbary Coast”, long dominated by Australian gangs, could only be pacified by popular militias?

More here.

Room-Temperature Superconductivity Achieved, but the superconductor requires crushing pressures to keep from falling apart

Charlie Wood in Quanta:

Yet while researchers celebrate the achievement, they stress that the newfound compound — created by a team led by Ranga Dias of the University of Rochester — will never find its way into lossless power lines, frictionless high-speed trains, or any of the revolutionary technologies that could become ubiquitous if the fragile quantum effect underlying superconductivity could be maintained in truly ambient conditions. That’s because the substance superconducts at room temperature only while being crushed between a pair of diamonds to pressures roughly 75% as extreme as those found in the Earth’s core.

Yet while researchers celebrate the achievement, they stress that the newfound compound — created by a team led by Ranga Dias of the University of Rochester — will never find its way into lossless power lines, frictionless high-speed trains, or any of the revolutionary technologies that could become ubiquitous if the fragile quantum effect underlying superconductivity could be maintained in truly ambient conditions. That’s because the substance superconducts at room temperature only while being crushed between a pair of diamonds to pressures roughly 75% as extreme as those found in the Earth’s core.

“People have talked about room-temperature superconductivity forever,” Pickard said. “They may not have quite appreciated that when we did it, we were going to do it at such high pressures.”

Materials scientists now face the challenge of discovering a superconductor that operates not only at normal temperatures but under everyday pressures, too. Certain features of the new compound raise hopes that the right blend of atoms could someday be found.

More here.

‘The Sea’: Read the story that won the 2020 Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-to-English translation

From Scroll.in:

The unanimous choice for the 2020 winner of the Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-English Translation is “The Sea” by Khalida Hussain, translated by Haider Shahbaz.

Haider Shahbaz’s translation of Khalida Hussain’s “Samundar” was chosen primarily for the quality of translation and secondarily on account of what the story has to offer in its English rendering. The selection of the Urdu text, the urgency of its translation, its flow – all were praiseworthy.

“The Sea” succeeds in capturing the poignancy of the original text, communicating it to the reader so that she can feel the wind in her face, smell the fresh sea breeze, touch the gritty sand beneath her feet, and share in the pain of displacement that underpins Hussain’s short story. This is a difficult task for any writer, and especially for one who works between languages as disparate as English and Urdu in their tonal register and literary sensibility.

Both judges have added a note encouraging the winner to work towards a collection of Khalida Hussain’s stories in English translation.

More here, including the English translation of the story.

The World After Coronavirus: Adil Najam interviews Ban Ki-moon about The Future of the United Nations

The Making of Malcolm X

Kerri Greenidge in The Atlantic:

To anyone walking through Roxbury, Massachusetts, the sounds that waft over Dale Street are far away—the fart of buses on Washington Street to the west and on Warren Street to the east. The sidewalk that abuts the bowfront brick rowhouses and wood-frame two-families with porch railings and multiple mailboxes feels comfortably quiet. And it is possible to forget that the recently renamed Nubian Square—Roxbury’s central business district—is less than a 10-minute walk away. In the early 1940s, when Boston’s El towered over what was then called Dudley Square, Ella Mae Little-Collins purchased a two-and-a-half-story house at 72 Dale Street, not far from Washington Park, and invited her 15-year-old half brother, Malcolm, to move in with her. Over the next five years, until he was arrested in January 1946 on charges of larceny, breaking and entering, and illegal possession of a firearm, Malcolm Little lived off and on at No. 72, walking the streets of Roxbury and the South End in his wide-brimmed hats and zoot suits.

To anyone walking through Roxbury, Massachusetts, the sounds that waft over Dale Street are far away—the fart of buses on Washington Street to the west and on Warren Street to the east. The sidewalk that abuts the bowfront brick rowhouses and wood-frame two-families with porch railings and multiple mailboxes feels comfortably quiet. And it is possible to forget that the recently renamed Nubian Square—Roxbury’s central business district—is less than a 10-minute walk away. In the early 1940s, when Boston’s El towered over what was then called Dudley Square, Ella Mae Little-Collins purchased a two-and-a-half-story house at 72 Dale Street, not far from Washington Park, and invited her 15-year-old half brother, Malcolm, to move in with her. Over the next five years, until he was arrested in January 1946 on charges of larceny, breaking and entering, and illegal possession of a firearm, Malcolm Little lived off and on at No. 72, walking the streets of Roxbury and the South End in his wide-brimmed hats and zoot suits.

When he described 1940s Black Boston to Alex Haley as they worked together on The Autobiography of Malcolm X, two decades of distance had left him with barely concealed disdain for the Dale Street neighborhood. The cocky teenager had once marveled at the number of Black people in Dudley Square and the upper South End. But the man known variously as “East Lansing Red,” Prisoner 22843, Malcolm X, and Malik el-Shabazz told Haley that the enclave where he and Ella once lived was a bastion of middle-class Black pretension and snobbery. Yet despite this disavowal, Black Boston had a profound effect on the figure whom the artist-activist Shirley Graham Du Bois later referred to as “the most promising and effective leader of American Negroes in this century.”

More here.

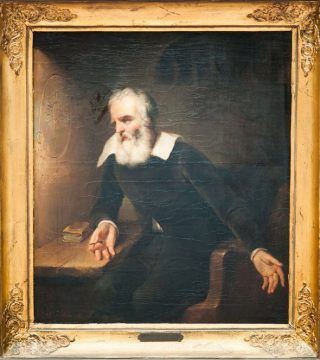

Did Galileo Truly Say, ‘And Yet It Moves’? A Modern Detective Story

Mario Livio in Scientific American:

“And yet it moves.” This may be the most famous line attributed to the renowned scientist Galileo Galilei. The “it” in the quote refers to Earth. “It moves” was a startling denial of the notion, adopted by the Catholic Church at the time, that Earth was at the center of the universe and therefore stood still. Galileo was convinced that model was wrong. Although he could not prove it, his astronomical observations and his experiments in mechanics led him to conclude that Earth and the other planets were revolving around the sun. That brings us to “and yet.” As much as Galileo may have hoped to convince the Church that in moving Earth from its anointed position, he was not contradicting Scripture, he did not fully appreciate that Church officials could not accept what they regarded as his impudent invasion into their exclusive province: theology.

“And yet it moves.” This may be the most famous line attributed to the renowned scientist Galileo Galilei. The “it” in the quote refers to Earth. “It moves” was a startling denial of the notion, adopted by the Catholic Church at the time, that Earth was at the center of the universe and therefore stood still. Galileo was convinced that model was wrong. Although he could not prove it, his astronomical observations and his experiments in mechanics led him to conclude that Earth and the other planets were revolving around the sun. That brings us to “and yet.” As much as Galileo may have hoped to convince the Church that in moving Earth from its anointed position, he was not contradicting Scripture, he did not fully appreciate that Church officials could not accept what they regarded as his impudent invasion into their exclusive province: theology.

During his trial for suspicion of heresy, Galileo chose his words carefully. It was only after the trial, angered by his conviction no doubt, that he was said to have muttered to the inquisitors, “Eppur si muove”(“And yet it moves)”, as if to say that they may have won this battle, but in the end, truth would win out. But did Galileo really utter those famous words? There is no doubt that he thought along those lines. His bitterness about the trial; the fact that he had been forced to abjure and recant his life’s work; the humiliating reality that his book Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems had been put on the Church’s Index of Prohibited Books; and his deep contempt for the inquisitors who judged him continually occupied his mind for all the years following the trial. We can also be certain that he did not (as legend has it) mutter that phrase in front of the inquisitors. Doing so would have been insanely risky. But did he say it at all? If not, when and how did the myth about this motto start circulating?

More here.

On Jewish Community and Identity in Jacques Derrida’s Algeria

Peter Salmon at Literary Hub:

The question of where the Juifs d’Algérie, the community into which Jackie was born, fitted into Algerian society was, inevitably, a complex one. Derrida’s family were Sephardic, and claimed roots from Toledo in Spain. In 1870, Algerian Jews were granted French citizenship by the Crémieux Decree, which brought their rights in line with the rest of the pied-noir (black foot, i.e. wearing shoes) population of Algeria. The majority Muslim population had no such rights, and were subject to the Code de l’indigénat, which gave them, at best, second-class status before the law. Although tensions had not reached the scale that would lead to and accompany the Algerian War, they were already present. At the same cinemas where Aimé and Georgette had watched Chaplin, Algerians “clapped and cheered when the hero made stirring speeches about Swiss independence in William Tell and when the Foreign Legionnaire heroes in Le Hommes Sans Nom(The Men with No Name) were shot by Moroccan insurgents.”

The question of where the Juifs d’Algérie, the community into which Jackie was born, fitted into Algerian society was, inevitably, a complex one. Derrida’s family were Sephardic, and claimed roots from Toledo in Spain. In 1870, Algerian Jews were granted French citizenship by the Crémieux Decree, which brought their rights in line with the rest of the pied-noir (black foot, i.e. wearing shoes) population of Algeria. The majority Muslim population had no such rights, and were subject to the Code de l’indigénat, which gave them, at best, second-class status before the law. Although tensions had not reached the scale that would lead to and accompany the Algerian War, they were already present. At the same cinemas where Aimé and Georgette had watched Chaplin, Algerians “clapped and cheered when the hero made stirring speeches about Swiss independence in William Tell and when the Foreign Legionnaire heroes in Le Hommes Sans Nom(The Men with No Name) were shot by Moroccan insurgents.”

more here.

Urdu Poetry, The Soviet Union And India’s Right-Wing Government

Gargi Binju at 3:AM Magazine:

As real border walls were being put up, so were metaphorical borders. The Urdu writers had been published freely in both countries until this point. There were hardly any Urdu literary journals at the time in India because Indian Urdu writers had published in Pakistan where the readership was larger; Urdu being Pakistan’s national language. The war changed that. New Urdu journals arose in India, most notably Shabkhoon launched by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi in Allahabad. Writers, Urdu or not, wanted to address the crisis of the war. They criticized the Progressives because their answers were old and dated. Marxists and Socialists were under attack in both Pakistan and India. In Pakistan, there was a call of national cultural unity, with Urdu at its center. Before this year, Bhasha Poetry, which freely took words from Indian languages other than Urdu was popular in Pakistan. After, the form quietly died.

As real border walls were being put up, so were metaphorical borders. The Urdu writers had been published freely in both countries until this point. There were hardly any Urdu literary journals at the time in India because Indian Urdu writers had published in Pakistan where the readership was larger; Urdu being Pakistan’s national language. The war changed that. New Urdu journals arose in India, most notably Shabkhoon launched by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi in Allahabad. Writers, Urdu or not, wanted to address the crisis of the war. They criticized the Progressives because their answers were old and dated. Marxists and Socialists were under attack in both Pakistan and India. In Pakistan, there was a call of national cultural unity, with Urdu at its center. Before this year, Bhasha Poetry, which freely took words from Indian languages other than Urdu was popular in Pakistan. After, the form quietly died.

more here.

Glenn Gould – Off the Record

Thursday Poem

Family Trees

—for the 2016 Guam Soil and Water Conservation Districts’ Educator Symposium

1

Before we enter the jungle, my dad

asks permission of the spirits who dwell

within. He walks slowly, with care,

to teach me, like his father taught him,

how to show respect. Then he stops

and closes his eyes to teach me

how to listen. Ekungok, as the winds

exhale and billow the canopy, tremble

the understory, and conduct the wild

orchestra of all breathing things.

2

“Niyok, Lemmai, Ifit, Yoga’, Nunu,” he chants

in a tone of reverence, calling forth the names

of each tree, each elder, who has provided us

with food and medicine, clothes and tools,

canoes and shelter. Like us, they grew in dark

wombs, sprouted from seeds, were nourished

by the light. Like us, they survived the storms

of conquest. Like us, roots anchor them to this

island, giving breath, giving strength to reach

towards the Pacific sky and blossom.

3

“When you take,” my dad says, “Take with

gratitude, and never more than what you need.”

He teaches me the phrase, “eminent domain,”

which means “theft,” means “to turn a place

of abundance into a base of destruction.”

The military uprooted trees with bulldozers,

paved the fertile earth with concrete, and planted

toxic chemicals and ordnances in the ground.

Barbed wire fences spread like invasive vines,

whose only fruit are the cancerous tumors

that bloom on every branch of our family tree.

Wednesday, October 14, 2020

Biology’s next great horizon is to understand cells, tissues and organisms as agents with agendas

Michael Levin and Daniel C. Dennett in Aeon:

Biologists like to think of themselves as properly scientific behaviourists, explaining and predicting the ways that proteins, organelles, cells, plants, animals and whole biota behave under various conditions, thanks to the smaller parts of which they are composed. They identify causal mechanisms that reliably execute various functions such as copying DNA, attacking antigens, photosynthesising, discerning temperature gradients, capturing prey, finding their way back to their nests and so forth, but they don’t think that this acknowledgment of functions implicates them in any discredited teleology or imputation of reasons and purposes or understanding to the cells and other parts of the mechanisms they investigate.

Biologists like to think of themselves as properly scientific behaviourists, explaining and predicting the ways that proteins, organelles, cells, plants, animals and whole biota behave under various conditions, thanks to the smaller parts of which they are composed. They identify causal mechanisms that reliably execute various functions such as copying DNA, attacking antigens, photosynthesising, discerning temperature gradients, capturing prey, finding their way back to their nests and so forth, but they don’t think that this acknowledgment of functions implicates them in any discredited teleology or imputation of reasons and purposes or understanding to the cells and other parts of the mechanisms they investigate.

But when cognitive science turned its back on behaviourism more than 50 years ago and began dealing with signals and internal maps, goals and expectations, beliefs and desires, biologists were torn. All right, they conceded, people and some animals have minds; their brains are physical minds – not mysterious dualistic minds – processing information and guiding purposeful behaviour; animals without brains, such as sea squirts, don’t have minds, nor do plants or fungi or microbes. They resisted introducing intentional idioms into their theoretical work, except as useful metaphors when teaching or explaining to lay audiences. Genes weren’t really selfish, antibodies weren’t really seeking, cells weren’t really figuring out where they were. These little biological mechanisms weren’t really agents with agendas, even though thinking of them as if they were often led to insights.

We think that this commendable scientific caution has gone too far, putting biologists into a straitjacket that prevents them from exploring the most promising hypotheses, just as behaviourism prevented psychologists from seeing how their subjects’ measurable behaviour could be interpreted as effects of hopes, beliefs, plans, fears, intentions, distractions and so forth.

More here.

Bats, bugs, and beauty: The best microscopy images of 2020