Charlie Tyson in The Hedgehog Review:

A few years ago, I was listening to a recording of the Tannhäuser overture on YouTube. Whether out of glazed torpor or instinctive masochism, I found myself scrolling down to read the comments.

A few years ago, I was listening to a recording of the Tannhäuser overture on YouTube. Whether out of glazed torpor or instinctive masochism, I found myself scrolling down to read the comments.

Now, the adage “Don’t read the comments” is, as ever, a wise rule—though increasingly difficult to implement as our digital public sphere turns into one large acidic comments section. But the corner of YouTube devoted to sharing recordings and performances of art music and opera is a gentle, sometimes genteel, subculture. Go to nearly any video of Bach, Schubert, Vivaldi, or Mozart, and you will find hundreds of comments that would strike any jaded young online American as ludicrously heartwarming. Classical Music Land is an unlikely utopia where listener-viewers from around the world, writing in dozens of languages, passionately and unironically extol the glory of music and the beauty of the human spirit.

A rather different community had assembled around Tannhäuser. “Hail our people, hail Wagner!” one commenter cheered. “Brothers…we must defend Europe!” sounded another. “A lot of Bad Goys on here,” a third remarked. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised. But when you are journeying through Classical Music Land and end up at a Nazi convention, you have to ask whether you need a new map.

More here.

Imagine you were locked in a sealed room, with no way to access the outside world but a few screens showing a view of what’s outside. Seems scary and limited, but that’s essentially the situation that our brains find themselves in — locked in our skulls, with only the limited information from a few unreliable sensory modalities to tell them what’s going on inside. Neuroscientist David Eagleman has long been interested in how the brain processes that sensory input, and also how we might train it to learn completely new ways of accessing the outside world, with important ramifications for virtual reality and novel brain/computer interface techniques.

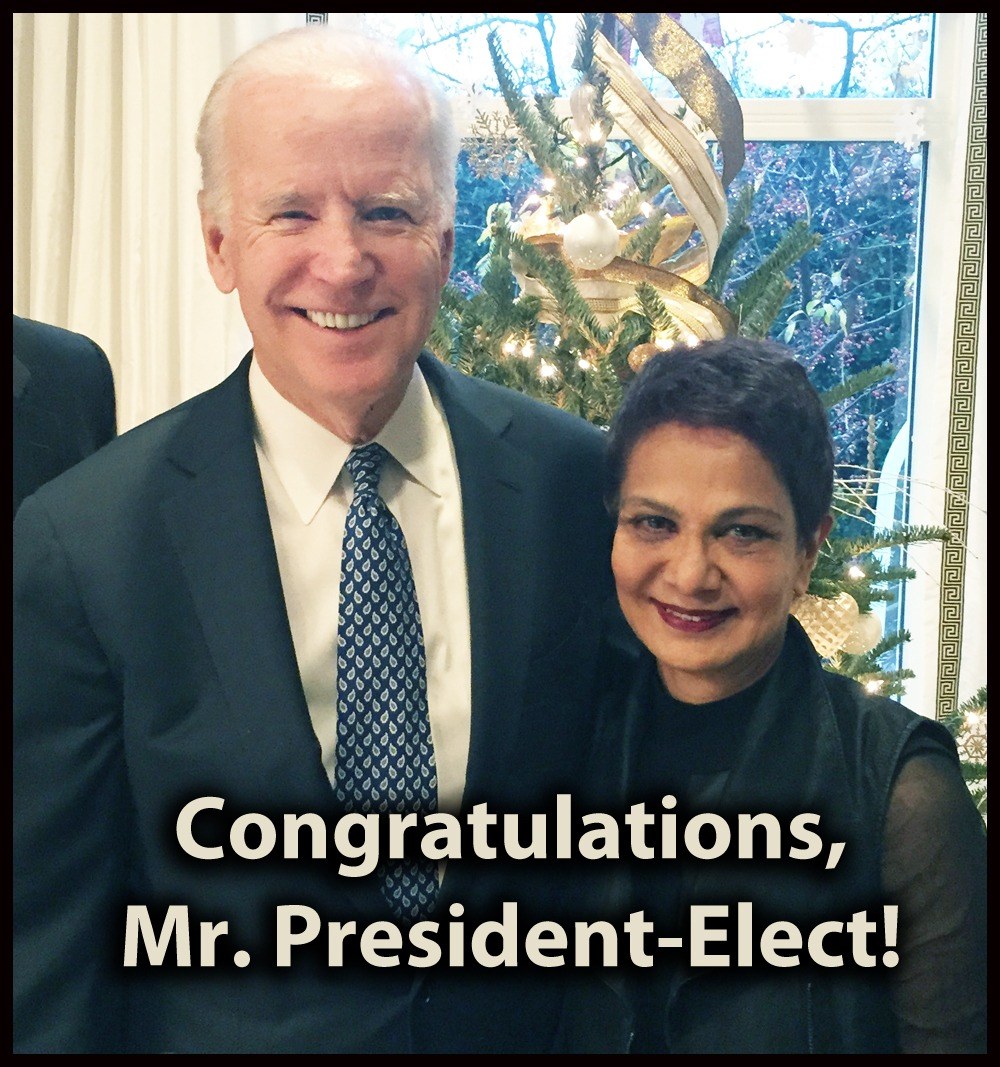

Imagine you were locked in a sealed room, with no way to access the outside world but a few screens showing a view of what’s outside. Seems scary and limited, but that’s essentially the situation that our brains find themselves in — locked in our skulls, with only the limited information from a few unreliable sensory modalities to tell them what’s going on inside. Neuroscientist David Eagleman has long been interested in how the brain processes that sensory input, and also how we might train it to learn completely new ways of accessing the outside world, with important ramifications for virtual reality and novel brain/computer interface techniques. The election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris comes as an enormous relief. Our democracy has been saved from a second Trump term, and arguably saved as such. Yet the outcome falls short of expressing a clear rebuke of Trumpism. The GOP now has a choice: take the defeat to heart and rebrand, or double down on the Trumpist program.

The election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris comes as an enormous relief. Our democracy has been saved from a second Trump term, and arguably saved as such. Yet the outcome falls short of expressing a clear rebuke of Trumpism. The GOP now has a choice: take the defeat to heart and rebrand, or double down on the Trumpist program. It works! Scientists have greeted with cautious optimism a press-release declaring positive interim results from a coronavirus vaccine trial — the first to report from the final, ‘phase III’ round of human testing. Drug company Pfizer’s announcement on 9 November offers the first compelling evidence that a vaccine can prevent COVID-19 — and bodes well for other COVID-19 vaccines in development. But the information released at this early stage does not answer key questions that will determine whether the Pfizer vaccine, and others like it, can prevent the most severe cases or quell the coronavirus pandemic. “We need to see the data in the end, but that still doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm. This is fantastic,” says Florian Krammer, a virologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who is also one of the trial’s more than 40,000 participants. “I hope I’m not in the placebo group.”

It works! Scientists have greeted with cautious optimism a press-release declaring positive interim results from a coronavirus vaccine trial — the first to report from the final, ‘phase III’ round of human testing. Drug company Pfizer’s announcement on 9 November offers the first compelling evidence that a vaccine can prevent COVID-19 — and bodes well for other COVID-19 vaccines in development. But the information released at this early stage does not answer key questions that will determine whether the Pfizer vaccine, and others like it, can prevent the most severe cases or quell the coronavirus pandemic. “We need to see the data in the end, but that still doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm. This is fantastic,” says Florian Krammer, a virologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who is also one of the trial’s more than 40,000 participants. “I hope I’m not in the placebo group.” Zamyatin is among the few gifted twentieth-century writers who responded to ideological tyranny by poetically integrating mathematical science into a philosophical anthropology. Dostoyevsky’s literary topographies of the soul are the

Zamyatin is among the few gifted twentieth-century writers who responded to ideological tyranny by poetically integrating mathematical science into a philosophical anthropology. Dostoyevsky’s literary topographies of the soul are the  Three is the second of the four brilliant and enigma-ridden novels that Ann Quin published before drowning off the coast of Brighton in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven. The mysterious character S—the absent protagonist or antiheroine hypotenuse of this love-triangle tale—dies in similar fashion … or perhaps she’s stabbed to death by a gang of nameless, faceless men before her body washes up onshore … or perhaps the stabbed dead body that washes up onshore is someone else… It’s difficult to tell. And the telling is difficult, too. And I would submit that it’s precisely these difficulties that make this gory story normal.

Three is the second of the four brilliant and enigma-ridden novels that Ann Quin published before drowning off the coast of Brighton in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven. The mysterious character S—the absent protagonist or antiheroine hypotenuse of this love-triangle tale—dies in similar fashion … or perhaps she’s stabbed to death by a gang of nameless, faceless men before her body washes up onshore … or perhaps the stabbed dead body that washes up onshore is someone else… It’s difficult to tell. And the telling is difficult, too. And I would submit that it’s precisely these difficulties that make this gory story normal. Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), Russia’s greatest comic writer, thoroughly baffled his contemporaries. Strange, peculiar, wacky, weird, bizarre, and other words indicating enigmatic oddity recur in descriptions of him. “What an intelligent, queer, and sick creature!” remarked Turgenev; another major prose writer, Sergey Aksakov, referred to the “unintelligible strangeness of his spirit.” When Gogol died, the poet Pyotr Vyazemsky sighed, “Your life was an enigma, so is today your death.”

Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), Russia’s greatest comic writer, thoroughly baffled his contemporaries. Strange, peculiar, wacky, weird, bizarre, and other words indicating enigmatic oddity recur in descriptions of him. “What an intelligent, queer, and sick creature!” remarked Turgenev; another major prose writer, Sergey Aksakov, referred to the “unintelligible strangeness of his spirit.” When Gogol died, the poet Pyotr Vyazemsky sighed, “Your life was an enigma, so is today your death.” Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution.

Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution. Dear Dan,

Dear Dan, You can do whatever you want with your morals, forgive people or not. But your duties as a citizen are somewhat different than the duties you might have as, say, a Christian (the kind who strives to follow the gospel), and here forgiveness is not so much what is required as, simply, recognition of a common plight. This civic virtue overlaps, admittedly, with the moral; it is difficult to articulate it in terms that do not come across as moralising, and certainly it would be an impediment to its realisation to articulate it in the bare terms of calculative strategy. In France it is traditionally articulated in terms of fraternité, which seems to strike just the right note between strategy and moralising. We need to hold things together somehow; in a real family unit this might have to pass through an overtly moral gesture of forgiveness, but in a polity what we should perhaps expect is that people aspire at least to a recognition of their fellow citizens through a lens that represents them as brothers and sisters.

You can do whatever you want with your morals, forgive people or not. But your duties as a citizen are somewhat different than the duties you might have as, say, a Christian (the kind who strives to follow the gospel), and here forgiveness is not so much what is required as, simply, recognition of a common plight. This civic virtue overlaps, admittedly, with the moral; it is difficult to articulate it in terms that do not come across as moralising, and certainly it would be an impediment to its realisation to articulate it in the bare terms of calculative strategy. In France it is traditionally articulated in terms of fraternité, which seems to strike just the right note between strategy and moralising. We need to hold things together somehow; in a real family unit this might have to pass through an overtly moral gesture of forgiveness, but in a polity what we should perhaps expect is that people aspire at least to a recognition of their fellow citizens through a lens that represents them as brothers and sisters. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has criticised the Democratic party for incompetence in a no-holds-barred, post-election

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has criticised the Democratic party for incompetence in a no-holds-barred, post-election  IN OLIVER HIRSCHBIEGEL’S

IN OLIVER HIRSCHBIEGEL’S