Mark Oprea in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

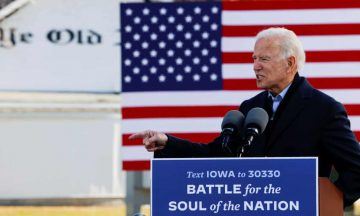

ON JULY 21, 2016, the Republican National Convention was in full swing and delegates in ruddy Americana and cowboy attire packed the Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena. Although it’s hard for most of us to recall, this was a time where even staunch Republicans were doubting Trump’s ascendency to the United States’s highest office. I was there, and remember it fondly, and was intrigued as to why those who did want Trump were willing to vote for a man who had called Mexicans rapists and had made fun of a handicapped New York Times journalist. A 52-year-old delegate from Vermont stressed the usual three prongs: the border, anti-terrorism, the military. Trump’s insensitivity mattered not. “To me,” the delegate said, “if you’re not safe, then you’ve got nothing.”

ON JULY 21, 2016, the Republican National Convention was in full swing and delegates in ruddy Americana and cowboy attire packed the Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena. Although it’s hard for most of us to recall, this was a time where even staunch Republicans were doubting Trump’s ascendency to the United States’s highest office. I was there, and remember it fondly, and was intrigued as to why those who did want Trump were willing to vote for a man who had called Mexicans rapists and had made fun of a handicapped New York Times journalist. A 52-year-old delegate from Vermont stressed the usual three prongs: the border, anti-terrorism, the military. Trump’s insensitivity mattered not. “To me,” the delegate said, “if you’re not safe, then you’ve got nothing.”

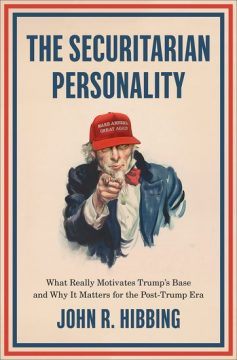

The same search for the soul of the average Trump diehard is found in John Hibbing’s The Securitarian Personality, a 304-page-long petri dish observation of the brain matter that lies tucked in the belts of MAGA hats. Using Theodor Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality as its theoretical base, Hibbing delves into the various facets of personality, demographics, behavior, and mindset that compose both devoted and on-the-fence Trump supporters and their conservative cousins, while tip-toeing across the tightrope strung between right-leaning sympathy and “racist” accusation.

More here.

In a series of breakthrough papers, theoretical physicists have come tantalizingly close to resolving the

In a series of breakthrough papers, theoretical physicists have come tantalizingly close to resolving the  Five years ago, American journalists called me following the terrorist attack that took the lives of my former colleagues and friends at Charlie Hebdo. They all thought that we were going to elect Marine Le Pen. I tried to explain to them that it’s precisely because there is a leftist movement associated with Charlie—both anti-racist and secular, a left that remains lucid about the dangers of extremism—that we had a chance to avoid that fate. But my explanations were in vain.

Five years ago, American journalists called me following the terrorist attack that took the lives of my former colleagues and friends at Charlie Hebdo. They all thought that we were going to elect Marine Le Pen. I tried to explain to them that it’s precisely because there is a leftist movement associated with Charlie—both anti-racist and secular, a left that remains lucid about the dangers of extremism—that we had a chance to avoid that fate. But my explanations were in vain. The evolutionary explanation for human connection to nature is a colossal safari through the African savanna, where our ancestors fought, fed, and frolicked for millions of years. The biologist E.O. Wilson speculated on this story in Biophilia, a slim volume on human attraction to nature. Wilson defined biophilia as an “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes.” He argued that if other animals are adapted to their environments and are best-suited to the environments in which they evolved—for example, a thick white coat serves the polar bear well in its native cold and snowy Arctic—then is it possible that humans too, despite our ability to live anywhere on this planet, are best adapted to the particular environment in which we evolved?

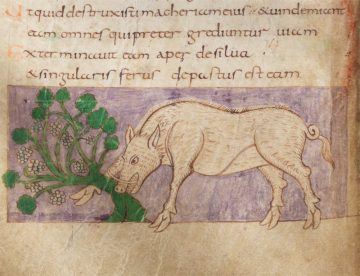

The evolutionary explanation for human connection to nature is a colossal safari through the African savanna, where our ancestors fought, fed, and frolicked for millions of years. The biologist E.O. Wilson speculated on this story in Biophilia, a slim volume on human attraction to nature. Wilson defined biophilia as an “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes.” He argued that if other animals are adapted to their environments and are best-suited to the environments in which they evolved—for example, a thick white coat serves the polar bear well in its native cold and snowy Arctic—then is it possible that humans too, despite our ability to live anywhere on this planet, are best adapted to the particular environment in which we evolved? These are ancient texts, but the pig’s characterization as a ravenous and dirty animal has transcended particular historical moments. Christians in early medieval Europe made the same associations, and so do we. More than one historian has pointed this out over the years, partly with the goal of rehabilitating the animals’ reputation. But this flat stereotype, this singular beast, was not the only profile a pig could have, even in the past: “premodern” views were subtler than the shorthand symbolism suggests. In late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, farmers, policy makers, and philosophers were perfectly capable of holding multiple views of pigs simultaneously, of playing into a familiar caricature but also of honing in on the complexities of the species. They saw that pigs were not merely commodities that provided humans with meat or symbols that worked as handy metaphors. They were also creatures that were capable of adapting to and altering their environments, including the human environments that only partially constrained them. Pigs were difficult to fully domesticate, both physically and conceptually. They called attention to themselves and required some engagement with their complex lives.

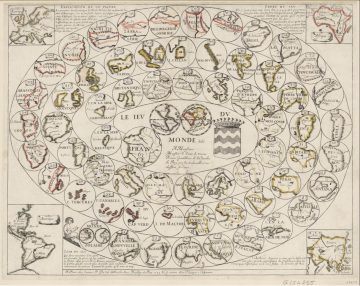

These are ancient texts, but the pig’s characterization as a ravenous and dirty animal has transcended particular historical moments. Christians in early medieval Europe made the same associations, and so do we. More than one historian has pointed this out over the years, partly with the goal of rehabilitating the animals’ reputation. But this flat stereotype, this singular beast, was not the only profile a pig could have, even in the past: “premodern” views were subtler than the shorthand symbolism suggests. In late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, farmers, policy makers, and philosophers were perfectly capable of holding multiple views of pigs simultaneously, of playing into a familiar caricature but also of honing in on the complexities of the species. They saw that pigs were not merely commodities that provided humans with meat or symbols that worked as handy metaphors. They were also creatures that were capable of adapting to and altering their environments, including the human environments that only partially constrained them. Pigs were difficult to fully domesticate, both physically and conceptually. They called attention to themselves and required some engagement with their complex lives. In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement, or Game of Geography, the latest in his family’s board game series. Allegedly based on a 1749 travelogue, “the Grand Tour of Europe, by Dr. Nugent,” it combined learned pretensions with simple rules. “Having agreed to make an elegant and instructive TOUR of EUROPE,” players took turns rolling an eight-sided “Totum” and moving their “Pillars” through the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first was “entitled to the applause of the company and honor of being esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler”: an enviable but deceptive accolade. In fact, erudition and swiftness were inversely correlated in Bowles’s game; being “instructed” required that your Pillar be delayed.

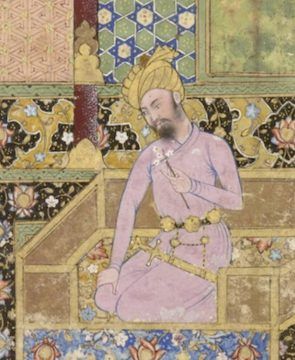

In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement, or Game of Geography, the latest in his family’s board game series. Allegedly based on a 1749 travelogue, “the Grand Tour of Europe, by Dr. Nugent,” it combined learned pretensions with simple rules. “Having agreed to make an elegant and instructive TOUR of EUROPE,” players took turns rolling an eight-sided “Totum” and moving their “Pillars” through the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first was “entitled to the applause of the company and honor of being esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler”: an enviable but deceptive accolade. In fact, erudition and swiftness were inversely correlated in Bowles’s game; being “instructed” required that your Pillar be delayed. At the end of 1525, Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur, a Timurid poet-prince from Farghana in Central Asia, descended the Khyber Pass with a small army of hand-picked followers; with him he brought some of the first modern muskets and cannons seen in India. With these he defeated the Delhi Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, and established his garden-capital at Agra.

At the end of 1525, Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur, a Timurid poet-prince from Farghana in Central Asia, descended the Khyber Pass with a small army of hand-picked followers; with him he brought some of the first modern muskets and cannons seen in India. With these he defeated the Delhi Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, and established his garden-capital at Agra. BioNTech began work on the vaccine in January, after Dr. Sahin read an article in the medical journal The Lancet that left him convinced that the coronavirus, at the time spreading quickly in parts of China, would explode into a full-blown pandemic. Scientists at the company, based in Mainz, Germany, canceled vacations and set to work on what they called Project Lightspeed.

BioNTech began work on the vaccine in January, after Dr. Sahin read an article in the medical journal The Lancet that left him convinced that the coronavirus, at the time spreading quickly in parts of China, would explode into a full-blown pandemic. Scientists at the company, based in Mainz, Germany, canceled vacations and set to work on what they called Project Lightspeed. Obama’s attempt to reconcile irreconcilable forces, to paper over the chasms, arguably gave Donald Trump his opening. Rather than confronting the banks whose reckless greed had caused the financial crisis, he allowed his Treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, to “foam the runway” for them by allowing 10 million families to

Obama’s attempt to reconcile irreconcilable forces, to paper over the chasms, arguably gave Donald Trump his opening. Rather than confronting the banks whose reckless greed had caused the financial crisis, he allowed his Treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, to “foam the runway” for them by allowing 10 million families to  The manufacture of many chemicals important to human health and comfort consumes fossil fuels, thereby contributing to extractive processes, carbon dioxide emissions and climate change. A new approach employs sunlight to convert waste carbon dioxide into these needed chemicals, potentially reducing emissions in two ways: by using the unwanted gas as a raw material and sunlight, not fossil fuels, as the source of energy needed for production. This process is becoming increasingly feasible thanks to advances in sunlight-activated catalysts, or photocatalysts. In recent years investigators have developed photocatalysts that break the resistant double bond between carbon and oxygen in carbon dioxide. This is a critical first step in creating “solar” refineries that produce useful compounds from the waste gas—including “platform” molecules that can serve as raw materials for the synthesis of such varied products as medicines, detergents, fertilizers and textiles.

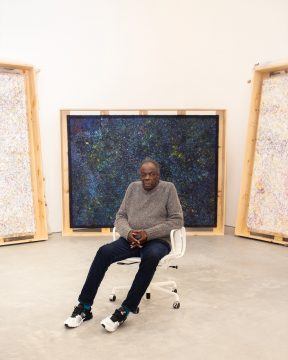

The manufacture of many chemicals important to human health and comfort consumes fossil fuels, thereby contributing to extractive processes, carbon dioxide emissions and climate change. A new approach employs sunlight to convert waste carbon dioxide into these needed chemicals, potentially reducing emissions in two ways: by using the unwanted gas as a raw material and sunlight, not fossil fuels, as the source of energy needed for production. This process is becoming increasingly feasible thanks to advances in sunlight-activated catalysts, or photocatalysts. In recent years investigators have developed photocatalysts that break the resistant double bond between carbon and oxygen in carbon dioxide. This is a critical first step in creating “solar” refineries that produce useful compounds from the waste gas—including “platform” molecules that can serve as raw materials for the synthesis of such varied products as medicines, detergents, fertilizers and textiles. The show’s main news is in sculpture: there are several small pyramids and one immense one, all raised slightly off the floor and built of innumerable horizontal sheets of laminated plywood with regularly spaced bands of aluminum. Gorgeously dyed in sumptuous color—bringing out and celebrating the textures of the wood grain—the blunt structures radiate like light sources. Do they suggest late entries in the repertoire of Minimalism? They do, but with a sense of re-starting the aesthetic from scratch—getting it right, even, at long last. The pieces play a role in another of the show’s revelations: a series of large (up to twenty feet wide) neo- or post- or, let’s say, para-color-field paintings that owe the ruggedness of their paint surfaces to incorporations of leftover pyramid sawdust. Bevelled edges flirt with object-ness, making the works seem fat material presentations, protuberant from walls, rather than pictures. But, as always with Gilliam, paint wins. Thick grounds in white or black are crazed with specks, splotches, and occasional dragged strokes of varied color. While you feel the weight of the wooden supports, your gaze loses itself in something like starry skies: dizzying impressions of infinite distance in tension with the dense grounds, which are complicated by tiny bits of collaged and overpainted wooden squares. Registering the jittery chromatic harmonies and occasional underlying structures—ghosts of geometry—takes time. Seemingly decorative at first glance, the paintings turn inexhaustibly absorbing and exciting when contemplated. Like everything else in this show of an artist who is old in years, they feel defiantly brand spanking new.

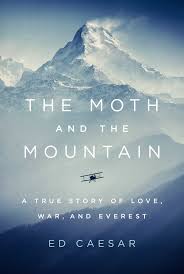

The show’s main news is in sculpture: there are several small pyramids and one immense one, all raised slightly off the floor and built of innumerable horizontal sheets of laminated plywood with regularly spaced bands of aluminum. Gorgeously dyed in sumptuous color—bringing out and celebrating the textures of the wood grain—the blunt structures radiate like light sources. Do they suggest late entries in the repertoire of Minimalism? They do, but with a sense of re-starting the aesthetic from scratch—getting it right, even, at long last. The pieces play a role in another of the show’s revelations: a series of large (up to twenty feet wide) neo- or post- or, let’s say, para-color-field paintings that owe the ruggedness of their paint surfaces to incorporations of leftover pyramid sawdust. Bevelled edges flirt with object-ness, making the works seem fat material presentations, protuberant from walls, rather than pictures. But, as always with Gilliam, paint wins. Thick grounds in white or black are crazed with specks, splotches, and occasional dragged strokes of varied color. While you feel the weight of the wooden supports, your gaze loses itself in something like starry skies: dizzying impressions of infinite distance in tension with the dense grounds, which are complicated by tiny bits of collaged and overpainted wooden squares. Registering the jittery chromatic harmonies and occasional underlying structures—ghosts of geometry—takes time. Seemingly decorative at first glance, the paintings turn inexhaustibly absorbing and exciting when contemplated. Like everything else in this show of an artist who is old in years, they feel defiantly brand spanking new. The Moth and the Mountain is a strange book. Several times this past month I’ve told friends about it, describing its central figure, Maurice Wilson: war hero, heartbreaker, daydreamer, globetrotter, irrepressible adventurer, the man who, in 1932, dreamed up a scheme to fly the moth of the title (a de Havilland biplane) on to Mount Everest, before hopping out and shinning up to the summit. My wide-eyed friends would blink and ask, ‘And this is a real story?’ and I’d nod, and then they’d ask the terminal question, ‘What happened next?’

The Moth and the Mountain is a strange book. Several times this past month I’ve told friends about it, describing its central figure, Maurice Wilson: war hero, heartbreaker, daydreamer, globetrotter, irrepressible adventurer, the man who, in 1932, dreamed up a scheme to fly the moth of the title (a de Havilland biplane) on to Mount Everest, before hopping out and shinning up to the summit. My wide-eyed friends would blink and ask, ‘And this is a real story?’ and I’d nod, and then they’d ask the terminal question, ‘What happened next?’ Stacey Abrams is the former Georgia state house minority leader, whose fierce fight for Georgians’ right to vote has been credited for potentially handing the state to the Democrats for the first time in 28 years. But Abrams has another identity: the novelist Selena Montgomery, a romance and thriller writer who has sold more than 100,000 copies of her eight novels.

Stacey Abrams is the former Georgia state house minority leader, whose fierce fight for Georgians’ right to vote has been credited for potentially handing the state to the Democrats for the first time in 28 years. But Abrams has another identity: the novelist Selena Montgomery, a romance and thriller writer who has sold more than 100,000 copies of her eight novels. You didn’t need to know every note of Nirvana’s angst-rock classic “In Bloom” to marvel at the spectacle of a little girl drumming along to the song in perfect synchronization last November, her face scrawled over with joy and passion. The internet is an open playing field for regular people performing impressive feats, and over a couple of years,

You didn’t need to know every note of Nirvana’s angst-rock classic “In Bloom” to marvel at the spectacle of a little girl drumming along to the song in perfect synchronization last November, her face scrawled over with joy and passion. The internet is an open playing field for regular people performing impressive feats, and over a couple of years,