Things That Fall

They say 420 drones and 24 missiles.

They say most intercepted.

They say two confirmed dead, but you know how the news lies

not by faking it, but by smoothing it.

They don’t say how long the sirens rang,

or if a dog got left on a balcony, or

if the man who always sells sunflowers at the corner

was standing there this time too.

In Lviv there was a girl who liked to draw planets.

Her teacher posted a video,

one of those voiceover ones

where someone says she had dreams,

and she did,

but she also had scabs on both knees and

once stole a pen from the bank just to see if she could.

I drank too much that night.

Watched the footage on mute.

Sometimes I think watching it with sound

makes it feel more real,

but sometimes the silence is worse

you start filling it in.

I don’t know what God wants.

I don’t know what we want.

Maybe it was always going to come to this,

drones over cities, missiles with names,

people saying “our defense was successful”

while putting plastic tarps over windows

where children used to tape paper snowflakes.

My neighbor left his porch light on all night again.

I knocked once but he didn’t answer.

Maybe he’s dead. Maybe he’s sleeping.

Maybe he’s praying in the way only people

who don’t believe in anything can.

There’s a way a city leans after it’s been hit.

Not physically

I mean it like a person who’s just gotten bad news

but hasn’t sat down yet.

One kindergarten’s roof caved in.

One subway station flooded.

One woman lost her hands.

Try writing a poem with no hands.

Try opening a can of peaches.

Try anything.

I used to think words could stop a war.

I used to think language had a kind of backbone.

But now even metaphors feel embarrassed.

Now even hope has to be rationed.

I would send this poem to her

if I thought it could reach her.

If I knew her name.

If I thought the shape of this sentence

could carry what didn’t burn.

But I don’t.

And it can’t.

And even if it could,

the signal wouldn’t hold.

Not with all that smoke in the sky.

by Sushanta Basumatary

from Rattle Magazine

— “The large-scale Russian aerial assault on Ukraine during the night of July 21st, in which over 420 drones and 24 missiles targeted multiple cities including Kyiv and Lviv. Ukrainian air defenses intercepted most of the projectiles, but civilian casualties and infrastructure damage were reported. This event has been described as one of the most intense attacks of the year and has drawn widespread international condemnation.” Sushanta Basumatary:

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In 1976 when we were both based in Brussels, my BBC mentor, the great Charles Wheeler, came back to the office from a grand US embassy party one evening and remarked: “The cleverest and most entertaining people at these things are always CIA. Makes it all the harder to understand why they get everything wrong.” An exaggeration, of course, but one with a degree of truth to it. Why has an organisation with huge amounts of money at its disposal, a record of recruiting the brightest and the best, and the widest of remits, failed to notch up a better record? It’s true that we may not know about many of the CIA’s successes. But we know about a lot of its failures, and some of them have marked US history ineradicably.

In 1976 when we were both based in Brussels, my BBC mentor, the great Charles Wheeler, came back to the office from a grand US embassy party one evening and remarked: “The cleverest and most entertaining people at these things are always CIA. Makes it all the harder to understand why they get everything wrong.” An exaggeration, of course, but one with a degree of truth to it. Why has an organisation with huge amounts of money at its disposal, a record of recruiting the brightest and the best, and the widest of remits, failed to notch up a better record? It’s true that we may not know about many of the CIA’s successes. But we know about a lot of its failures, and some of them have marked US history ineradicably.

Published by Hunters Point Press last year, the writings collected in

Published by Hunters Point Press last year, the writings collected in  You could say all of this in another way: Theo Huxtable was a nicely realized character but also a lofty ideal. What he meant was too much for any real person to carry around. Malcolm-Jamal Warner seemed miraculously able to pull it off. He’d been famous and highly visible at an alarmingly young age, but, unlike many other former child stars, he never seemed to feel much rancor about the experience, or resentment about lugging pure-minded Theo around with him for the rest of his life.

You could say all of this in another way: Theo Huxtable was a nicely realized character but also a lofty ideal. What he meant was too much for any real person to carry around. Malcolm-Jamal Warner seemed miraculously able to pull it off. He’d been famous and highly visible at an alarmingly young age, but, unlike many other former child stars, he never seemed to feel much rancor about the experience, or resentment about lugging pure-minded Theo around with him for the rest of his life. When the sun shines on your skin, what does it hit? When it causes a burn, what went wrong?

When the sun shines on your skin, what does it hit? When it causes a burn, what went wrong? M

M

In the weeks and months

In the weeks and months When Katie Thurston was diagnosed with Stage IV metastatic breast cancer earlier this year, at age 34, people kept telling her they knew someone with the same diagnosis. Solidarity, you might think. A helpful way to relate. Not exactly: Their friend or family member had died. This scenario is “pretty recurring,” says Thurston, who starred on season 17 of The Bachelorette, and while people have good intentions—they want you to know they have experience with what you’re going through—the remark doesn’t land well. “We understand that death is a possibility in this diagnosis,” she says. “I don’t need to hear that.”

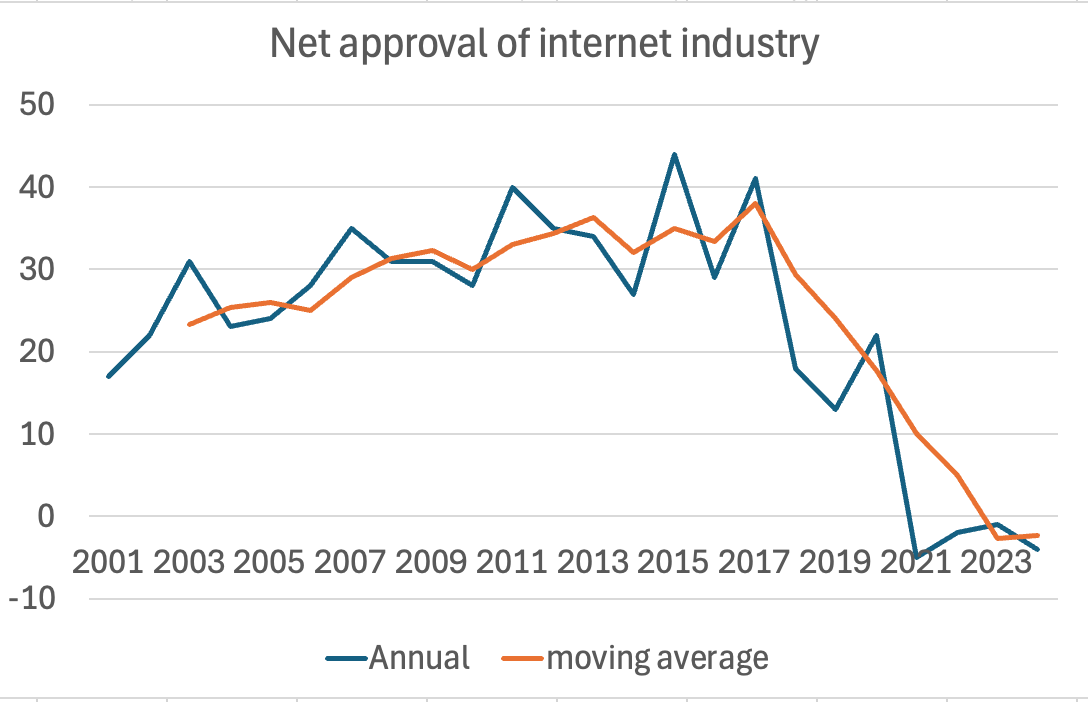

When Katie Thurston was diagnosed with Stage IV metastatic breast cancer earlier this year, at age 34, people kept telling her they knew someone with the same diagnosis. Solidarity, you might think. A helpful way to relate. Not exactly: Their friend or family member had died. This scenario is “pretty recurring,” says Thurston, who starred on season 17 of The Bachelorette, and while people have good intentions—they want you to know they have experience with what you’re going through—the remark doesn’t land well. “We understand that death is a possibility in this diagnosis,” she says. “I don’t need to hear that.” Many people sense that the United States is undergoing an

Many people sense that the United States is undergoing an  Where did Europe’s distinct Uralic family of languages — which includes Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian — come from? New research puts their origins a lot farther east than many thought.

Where did Europe’s distinct Uralic family of languages — which includes Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian — come from? New research puts their origins a lot farther east than many thought.