Yascha Mounk at his own Substack:

Yes, every fashionable conference has some panel on AI. Yes, social media is overrun with hypemen trying to alert their readers to the latest “mind-blowing” improvements of Grok or ChatGPT. But even as the maturation of AI technologies provides the inescapable background hum of our cultural moment, the mainstream outlets that pride themselves on their wisdom and erudition—even, in moments of particular self-regard, on their meaning-making mission—are lamentably failing to grapple with its epochal significance.

Yes, every fashionable conference has some panel on AI. Yes, social media is overrun with hypemen trying to alert their readers to the latest “mind-blowing” improvements of Grok or ChatGPT. But even as the maturation of AI technologies provides the inescapable background hum of our cultural moment, the mainstream outlets that pride themselves on their wisdom and erudition—even, in moments of particular self-regard, on their meaning-making mission—are lamentably failing to grapple with its epochal significance.

A recent viral essay in The New Yorker provides an extreme, but not an altogether atypical, illustration of the problem. “A.I. is frankly gross to me,” its author, Jia Tolentino, avows. “It launders bias into neutrality; it hallucinates; it can become ‘poisoned with its own projection of reality.’ The more frequently people use ChatGPT, the lonelier, and the more dependent on it, they become.” At least Tolentino has the honesty to acknowledge the astonishing fact that “I have never used ChatGPT.” Though the author considers herself a progressive, her basic attitude to new technologies resembles that of a reactionary 19th century priest who denounces the railways as the devil’s work—before proudly mentioning that he himself has, of course, never engaged in the sin of riding one.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The worst-case scenario of famine is currently playing out in the Gaza Strip.” These were the

The worst-case scenario of famine is currently playing out in the Gaza Strip.” These were the  A

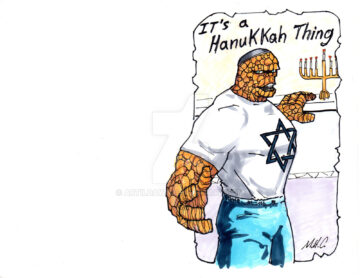

A IN 1975, JACK KIRBY, the “King of Comics” whose wildly kinetic art and sweeping visions had shaped the whole universe of Marvel Comics, sent a Hanukkah card to a friend, a young fan Kirby had met a few years earlier at a New York comics convention. At the time, Kirby had been living in Thousand Oaks, California, where he’d joined a Conservative synagogue, Temple Etz Chaim. An active temple member, Kirby occasionally read Torah portions at Shabbat services, visited the Hebrew School to demonstrate the art of drawing comics for the students, and later fulfilled a lifelong dream when he joined a congregational trip to Israel. So there was nothing remarkable about him sending a Hannukah card—except, that is, for

IN 1975, JACK KIRBY, the “King of Comics” whose wildly kinetic art and sweeping visions had shaped the whole universe of Marvel Comics, sent a Hanukkah card to a friend, a young fan Kirby had met a few years earlier at a New York comics convention. At the time, Kirby had been living in Thousand Oaks, California, where he’d joined a Conservative synagogue, Temple Etz Chaim. An active temple member, Kirby occasionally read Torah portions at Shabbat services, visited the Hebrew School to demonstrate the art of drawing comics for the students, and later fulfilled a lifelong dream when he joined a congregational trip to Israel. So there was nothing remarkable about him sending a Hannukah card—except, that is, for  There are plenty of healthy activities available at home, of course, from playing with your children to pursuing a hobby. But there are also consequences to our homebody lifestyle. Time in the house is more likely to be

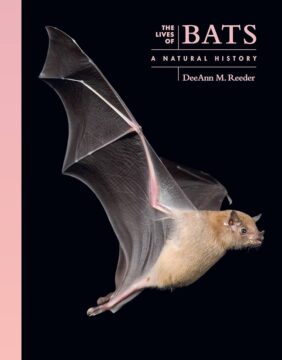

There are plenty of healthy activities available at home, of course, from playing with your children to pursuing a hobby. But there are also consequences to our homebody lifestyle. Time in the house is more likely to be  I have always had a soft spot for bats, and yet, after more than 500 reviews, this is the first bat book I cover here. Having now read this richly illustrated general introduction to their biology, I am even more engrossed with their many unique adaptations.

I have always had a soft spot for bats, and yet, after more than 500 reviews, this is the first bat book I cover here. Having now read this richly illustrated general introduction to their biology, I am even more engrossed with their many unique adaptations. “These days, I rarely think about her. And when I do, it’s happy thoughts. Because it was so nice. Very painful, but mostly wonderful. That’s why I wrote it down. To keep it with me. I know I will never forget it, but memories change. I thought if I found the right words to describe it exactly as it was, I could capture it, make it solid. Something I could hold in the palm of my hand forever.”

“These days, I rarely think about her. And when I do, it’s happy thoughts. Because it was so nice. Very painful, but mostly wonderful. That’s why I wrote it down. To keep it with me. I know I will never forget it, but memories change. I thought if I found the right words to describe it exactly as it was, I could capture it, make it solid. Something I could hold in the palm of my hand forever.” Roy, who is the author of novels like Booker Prize-winning

Roy, who is the author of novels like Booker Prize-winning  Everywhere they look, they find particles of pollution, like infinite spores in an endless contagion field. Scientists call that field the “exposome”: the sum of all external exposures encountered by each of us over a lifetime, which portion and shape our fate alongside genes and behavior. Humans are permeable creatures, and we navigate the world like cleaner fish, filtering the waste of civilization partly by absorbing it.

Everywhere they look, they find particles of pollution, like infinite spores in an endless contagion field. Scientists call that field the “exposome”: the sum of all external exposures encountered by each of us over a lifetime, which portion and shape our fate alongside genes and behavior. Humans are permeable creatures, and we navigate the world like cleaner fish, filtering the waste of civilization partly by absorbing it. T

T Her book design itself seems an exercise in branding. Only the word “Melania” on the cover. Nothing else, indicating not just fame but a sort of stardom, a woman known by only one name like singers Madonna and Beyoncé or, more fitting here, models Iman and Twiggy. Or a First Lady like Jackie, who may have been the only post-World War II president’s wife who could have published an autobiography with the same design and gotten away with it. One-third of this short book is made up of photographs of Melania, appropriate, I suppose, for a book about a model, but perhaps also a way for her to hide in plain sight, so to speak, to avoid having to talk about things she does not wish to talk about.

Her book design itself seems an exercise in branding. Only the word “Melania” on the cover. Nothing else, indicating not just fame but a sort of stardom, a woman known by only one name like singers Madonna and Beyoncé or, more fitting here, models Iman and Twiggy. Or a First Lady like Jackie, who may have been the only post-World War II president’s wife who could have published an autobiography with the same design and gotten away with it. One-third of this short book is made up of photographs of Melania, appropriate, I suppose, for a book about a model, but perhaps also a way for her to hide in plain sight, so to speak, to avoid having to talk about things she does not wish to talk about.