Ta-Nehisi Coates in The Atlantic:

By his own lights, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, ambassador, senator, sociologist, and itinerant American intellectual, was the product of a broken home and a pathological family.

By his own lights, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, ambassador, senator, sociologist, and itinerant American intellectual, was the product of a broken home and a pathological family.

…Influenced by the civil-rights movement, Moynihan focused on the black family. He believed that an undue optimism about the pending passage of civil-rights legislation was obscuring a pressing problem: a deficit of employed black men of strong character. He believed that this deficit went a long way toward explaining the African American community’s relative poverty. Moynihan began searching for a way to press the point within the Johnson administration. “I felt I had to write a paper about the Negro family,” Moynihan later recalled, “to explain to the fellows how there was a problem more difficult than they knew.” In March of 1965, Moynihan printed up 100 copies of a report he and a small staff had labored over for only a few months.

The report was called “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” Unsigned, it was meant to be an internal government document, with only one copy distributed at first and the other 99 kept locked in a vault. Running against the tide of optimism around civil rights, “The Negro Family” argued that the federal government was underestimating the damage done to black families by “three centuries of sometimes unimaginable mistreatment” as well as a “racist virus in the American blood stream,” which would continue to plague blacks in the future:

That the Negro American has survived at all is extraordinary—a lesser people might simply have died out, as indeed others have … But it may not be supposed that the Negro American community has not paid a fearful price for the incredible mistreatment to which it has been subjected over the past three centuries.

That price was clear to Moynihan.

More here.

T

T Back outside in the summer air, the summer frost heaves passed beneath my feet. I thought of Robert Walser, his little essay on walking, seeing everything afresh, the teeming world, the sap running, the beautiful phenomena, or his essay about Kleist walking around Thun, the mountainous Swiss village—“Bells are ringing. The people are leaving the hilltop church.” In those days, Walser wrote most of his stories in a micro-script so tiny it was assumed illegible for years, until two scholars with a magnifying lens revealed that the script, which looked like termite tracks, was actually Kurrent, a form of handwriting, medieval in origin, used by German speakers until the mid-twentieth century. Why am I describing Walser? Because I thought of him as I was walking on the sidewalk. Because Sontag describes Walser’s writing as a free fall of innocuous observations not governed by plot, in which “the important is redeemed as a species of the unimportant.” For instance, he ends the story “Autumn (II)” with the sentence, “In the city where I reside, a van Gogh exhibition is currently on view,” apropos of nothing. We don’t know what the broken white line means until much later. That’s why dream journalists write. That’s why journalists dream.

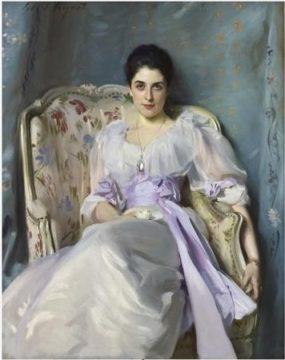

Back outside in the summer air, the summer frost heaves passed beneath my feet. I thought of Robert Walser, his little essay on walking, seeing everything afresh, the teeming world, the sap running, the beautiful phenomena, or his essay about Kleist walking around Thun, the mountainous Swiss village—“Bells are ringing. The people are leaving the hilltop church.” In those days, Walser wrote most of his stories in a micro-script so tiny it was assumed illegible for years, until two scholars with a magnifying lens revealed that the script, which looked like termite tracks, was actually Kurrent, a form of handwriting, medieval in origin, used by German speakers until the mid-twentieth century. Why am I describing Walser? Because I thought of him as I was walking on the sidewalk. Because Sontag describes Walser’s writing as a free fall of innocuous observations not governed by plot, in which “the important is redeemed as a species of the unimportant.” For instance, he ends the story “Autumn (II)” with the sentence, “In the city where I reside, a van Gogh exhibition is currently on view,” apropos of nothing. We don’t know what the broken white line means until much later. That’s why dream journalists write. That’s why journalists dream. It was often the case in the late 19th century that if you wanted to add a little prestige to your life you had your portrait painted by a notable portrait painter. Or you had your family painted, or just your wife. This latter idea was the thought that occurred to Sir Andrew Agnew, the 9th Baronet of Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. He was proud of his wife, perhaps in the way one is proud of a horse, or an elegant piece of furniture. He wanted others to be proud too. There was a lot of pride going around.

It was often the case in the late 19th century that if you wanted to add a little prestige to your life you had your portrait painted by a notable portrait painter. Or you had your family painted, or just your wife. This latter idea was the thought that occurred to Sir Andrew Agnew, the 9th Baronet of Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. He was proud of his wife, perhaps in the way one is proud of a horse, or an elegant piece of furniture. He wanted others to be proud too. There was a lot of pride going around. AI is a broad church, and like many churches, it has schisms.

AI is a broad church, and like many churches, it has schisms. Fears about

Fears about  While some academics (like John Boswell and Terry Castle) spent years arguing, with ever-decreasing success, that something like the contemporary “gay” or “lesbian” had always existed in relatively similar ways, “constructionist” models like those offered by Foucault and D’Emilio have become dominant in today’s academic histories about gay, lesbian, and trans lives. In the mainstream, however, it’s almost the reverse. If in the 1970s and 1980s there was a vibrant public activist culture in which both Queer History One and Two were debated, today most gay and lesbian people firmly rely on the former. The wages of nationalism are generous, and Queer History One’s story—you have always existed, you have dignity because you are like Great Men/Women—has proven to be an easier position from which to argue for the dispensation of civil rights and protections from the state. It’s unsurprising that this has become the mass-market narrative about homosexuality in the contemporary West: we’re born this way, and we always have been. Recognize us, and we’ll marry, pay taxes, and serve in the military.

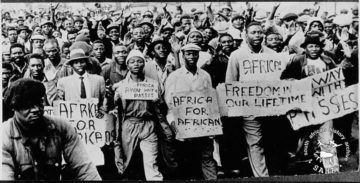

While some academics (like John Boswell and Terry Castle) spent years arguing, with ever-decreasing success, that something like the contemporary “gay” or “lesbian” had always existed in relatively similar ways, “constructionist” models like those offered by Foucault and D’Emilio have become dominant in today’s academic histories about gay, lesbian, and trans lives. In the mainstream, however, it’s almost the reverse. If in the 1970s and 1980s there was a vibrant public activist culture in which both Queer History One and Two were debated, today most gay and lesbian people firmly rely on the former. The wages of nationalism are generous, and Queer History One’s story—you have always existed, you have dignity because you are like Great Men/Women—has proven to be an easier position from which to argue for the dispensation of civil rights and protections from the state. It’s unsurprising that this has become the mass-market narrative about homosexuality in the contemporary West: we’re born this way, and we always have been. Recognize us, and we’ll marry, pay taxes, and serve in the military. Like all children in our exile community whose parents were members of the African National Congress, I attended Young Pioneers meetings every weekend. The meetings were like Sunday school sessions. Politics was our religion, and we worshipped at the altar of

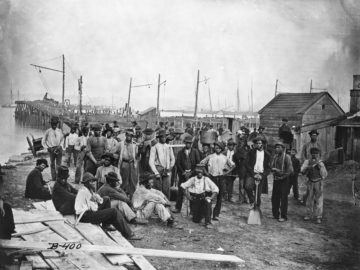

Like all children in our exile community whose parents were members of the African National Congress, I attended Young Pioneers meetings every weekend. The meetings were like Sunday school sessions. Politics was our religion, and we worshipped at the altar of  In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or  As an organizational psychologist, I’ve spent the past few years studying how to motivate people to think again. I’ve run experiments that led proponents of gun rights and gun safety to abandon some of their mutual animosity, and I even got Yankees fans to let go of their grudges against Red Sox supporters. But I don’t always practice what I teach.

As an organizational psychologist, I’ve spent the past few years studying how to motivate people to think again. I’ve run experiments that led proponents of gun rights and gun safety to abandon some of their mutual animosity, and I even got Yankees fans to let go of their grudges against Red Sox supporters. But I don’t always practice what I teach. As a semi-outsider, it’s fun for me to watch as a new era dawns in biology: one that adds ideas from physics, big data, computer science, and information theory to the usual biological toolkit. One of the big areas of study in this burgeoning field is the relationship between the basic bioinformatic building blocks (genes and proteins) to the macroscopic organism that eventually results. That relationship is not a simple one, as we’re discovering. Standard metaphors notwithstanding, an organism is not a machine based on genetic blueprints. I talk with biologist and information scientist Michael Levin about how information and physical constraints come together to make organisms and selves.

As a semi-outsider, it’s fun for me to watch as a new era dawns in biology: one that adds ideas from physics, big data, computer science, and information theory to the usual biological toolkit. One of the big areas of study in this burgeoning field is the relationship between the basic bioinformatic building blocks (genes and proteins) to the macroscopic organism that eventually results. That relationship is not a simple one, as we’re discovering. Standard metaphors notwithstanding, an organism is not a machine based on genetic blueprints. I talk with biologist and information scientist Michael Levin about how information and physical constraints come together to make organisms and selves.