B D McClay in The New Yorker:

Sophie Blind is dead. Her head was cut clean off her shoulders as she made a dash for a taxi and was hit by a car. She doesn’t seem to mind, though it is a little awkward. “I knew I was dead when I came,” she admits, “but I didn’t want to be the first to say it.” Besides, the event didn’t leave much of a mark: “in less than half an hour,” she informs us, “normal traffic was resumed.” Though death and decapitation seem like straightforward facts, Sophie is the heroine of a novel: “Divorcing,” by Susan Taubes. And in a novel both of these things, it turns out, can be meant in different ways.

Sophie Blind is dead. Her head was cut clean off her shoulders as she made a dash for a taxi and was hit by a car. She doesn’t seem to mind, though it is a little awkward. “I knew I was dead when I came,” she admits, “but I didn’t want to be the first to say it.” Besides, the event didn’t leave much of a mark: “in less than half an hour,” she informs us, “normal traffic was resumed.” Though death and decapitation seem like straightforward facts, Sophie is the heroine of a novel: “Divorcing,” by Susan Taubes. And in a novel both of these things, it turns out, can be meant in different ways.

“Divorcing” is the only published book by Taubes, who shortly after its release, in 1969, drowned herself “in a ski jacket and slacks,” as the East Hampton Star would report when her body was found. She was forty-one. She left behind letters, some of which have been published; some unpublished writing; some scattered academic articles; and a dissertation still sitting in Harvard’s archives. She is doomed, it would seem, to always appear in the shadow of her longer-lived, more prolific husband, Jacob Taubes, as interesting in her own right, no elaboration. Interesting—but not that interesting. After her death, as she’d say, normal traffic resumed.

Susan Taubes and Sophie Blind share certain biographical traits: psychoanalyst fathers, intellectual husbands, needy mothers, Hungarian childhoods, a conflicted and sometimes even disdainful relationship with their own Jewishness. Nonetheless, “Divorcing,” which was recently reissued by New York Review Books, does not read like a roman à clef. It does engage, as many of those books do, with the collapse of a marriage and a subsequent search for meaning. But while the sort of novels dropped in its blurbs—Renata Adler’s “Speedboat” and Elizabeth Hardwick’s “Sleepless Nights”—occupy a cool, collected “I” that remains untouched, “Divorcing” is a much more unsettled affair. From its opening pages, which unspool in both first and third persons, from a heroine who may or may not have a head, the book does not even attempt stability. Sophie’s death is a case in point; Taubes has no interest in establishing whether it is metaphorical or literal. The book goes on to include dreams, letters, therapy sessions, and a widening study of Sophie’s family history. There are conversational fragments that could be taking place at almost any time within the narrative. And in the final pages, Sophie emerges from a nap and from a sensory deprivation chamber. Was all of the preceding a dream? Does it matter? Sophie Blind is dead. She isn’t here. She isn’t, at all.

More here.

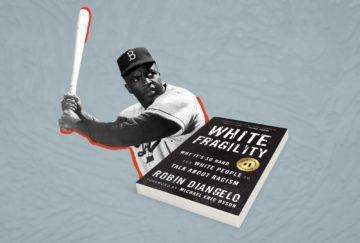

Robin DiAngelo’s book, White Fragility, has been on the New York Times best-seller list for over two years, much of that time ranked number one. The book is assigned frequently in college courses, and DiAngelo is in great demand as a “diversity” consultant to help corporations, universities, government agencies, and other institutions purge themselves of their white privilege. DiAngelo’s core message is that white Americans need to acknowledge their unconscious racial biases which make them, unwittingly in most cases, complicit in what she deems the U.S. racial caste system.

Robin DiAngelo’s book, White Fragility, has been on the New York Times best-seller list for over two years, much of that time ranked number one. The book is assigned frequently in college courses, and DiAngelo is in great demand as a “diversity” consultant to help corporations, universities, government agencies, and other institutions purge themselves of their white privilege. DiAngelo’s core message is that white Americans need to acknowledge their unconscious racial biases which make them, unwittingly in most cases, complicit in what she deems the U.S. racial caste system. A graduate student recently posed this question to me: What is the most common mistake that scholars make when they try to write about contemporary issues? Questions like this usually make me nervous, since the offices of cultural commentator and public intellectual remain very mysterious to me. But in this case, I had a ready answer because we all make the same mistake when writing about contemporary issues: Our writing process lacks sufficient resistance, hesitation, reconsideration—in short, friction.

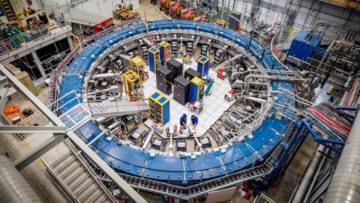

A graduate student recently posed this question to me: What is the most common mistake that scholars make when they try to write about contemporary issues? Questions like this usually make me nervous, since the offices of cultural commentator and public intellectual remain very mysterious to me. But in this case, I had a ready answer because we all make the same mistake when writing about contemporary issues: Our writing process lacks sufficient resistance, hesitation, reconsideration—in short, friction. As early as March, the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) will report a new measurement of the magnetism of the muon, a heavier, short-lived cousin of the electron. The effort entails measuring a single frequency with exquisite precision. In tantalizing

As early as March, the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) will report a new measurement of the magnetism of the muon, a heavier, short-lived cousin of the electron. The effort entails measuring a single frequency with exquisite precision. In tantalizing  Countless academic articles and self-help books sing to the same tune – characterising immediate gratification as a short-sighted hitch while praising the virtues of long-term thinking as a means for overcoming temptation. Many people have heard of the marshmallow

Countless academic articles and self-help books sing to the same tune – characterising immediate gratification as a short-sighted hitch while praising the virtues of long-term thinking as a means for overcoming temptation. Many people have heard of the marshmallow  Years ago, when my body simply was what it was, soft and long, before I had even contemplated changing it into anything else, I came across Martin Schoeller’s Female Bodybuilders on a bookstore display table. In it were studio-lit portraits of women whose faces had been reduced to bone and socket and vein, whose skin had been stained with spray tan and eyes outlined in shadow. Enormous muscles rose up to enclose their necks. They looked prehistoric, fossilized and eternal. I thought they had destroyed their chances at love. My mistake was to assume they were living under the star of sexual capital, as I was. After all, they wore the rhinestones and velvet of showgirls. What I didn’t yet understand was that bodybuilders are ruled by a different star, the same star that would later rule me, if only temporarily. It was dim and solitary, with enormous gravity. I still don’t have a name for it.

Years ago, when my body simply was what it was, soft and long, before I had even contemplated changing it into anything else, I came across Martin Schoeller’s Female Bodybuilders on a bookstore display table. In it were studio-lit portraits of women whose faces had been reduced to bone and socket and vein, whose skin had been stained with spray tan and eyes outlined in shadow. Enormous muscles rose up to enclose their necks. They looked prehistoric, fossilized and eternal. I thought they had destroyed their chances at love. My mistake was to assume they were living under the star of sexual capital, as I was. After all, they wore the rhinestones and velvet of showgirls. What I didn’t yet understand was that bodybuilders are ruled by a different star, the same star that would later rule me, if only temporarily. It was dim and solitary, with enormous gravity. I still don’t have a name for it. IN 1527, THE VENETIAN EXPLORER

IN 1527, THE VENETIAN EXPLORER  Last week, my whole outlook on the world was transformed by a sheet of blank paper. Not just any paper, but beautifully embossed stationery, silky to the touch and decadent to write on. It was a gift from a dear friend and colleague. We collaborate over Zoom every week, so I could have thanked him on video, but instead I wrote a short note of gratitude and love, and posted it to him. His delight on receipt a few days later mirrored my own, and we shared a moment of emotional connection.

Last week, my whole outlook on the world was transformed by a sheet of blank paper. Not just any paper, but beautifully embossed stationery, silky to the touch and decadent to write on. It was a gift from a dear friend and colleague. We collaborate over Zoom every week, so I could have thanked him on video, but instead I wrote a short note of gratitude and love, and posted it to him. His delight on receipt a few days later mirrored my own, and we shared a moment of emotional connection. Massachusetts abolished enslavement

Massachusetts abolished enslavement

What is memory? I carried with me for more than forty years the distorted and etiolated memory-trace of what I believed was an anti-nuclear protest concert, held around 1979, somewhere in America, featuring James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Peter Frampton, and other stars of that long-forgotten era. Throughout all these decades I was convinced that the concert had been called “Nukes Knocks [sic] Your Socks Off”, or perhaps, alternatively, “Nukes Knocks Yer Sox Off”.

What is memory? I carried with me for more than forty years the distorted and etiolated memory-trace of what I believed was an anti-nuclear protest concert, held around 1979, somewhere in America, featuring James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Peter Frampton, and other stars of that long-forgotten era. Throughout all these decades I was convinced that the concert had been called “Nukes Knocks [sic] Your Socks Off”, or perhaps, alternatively, “Nukes Knocks Yer Sox Off”. It’s a truism that what we see about the world is a small fraction of all that exists. At the simplest level of physics and biology, our senses are drastically limited; we only see a narrow spectrum of electromagnetic waves, and we only hear a narrow band of sound. We don’t feel neutrinos or dark matter at all, even as they pass through our bodies, and we can’t perceive microscopic objects. While science can help us overcome some of these limitations, they do shape how we think about the world. Ziya Tong takes this idea and expands it to include the parts of our social and moral worlds that are effectively invisible to us — from where our food comes from to how we decide how wealth is allocated in society.

It’s a truism that what we see about the world is a small fraction of all that exists. At the simplest level of physics and biology, our senses are drastically limited; we only see a narrow spectrum of electromagnetic waves, and we only hear a narrow band of sound. We don’t feel neutrinos or dark matter at all, even as they pass through our bodies, and we can’t perceive microscopic objects. While science can help us overcome some of these limitations, they do shape how we think about the world. Ziya Tong takes this idea and expands it to include the parts of our social and moral worlds that are effectively invisible to us — from where our food comes from to how we decide how wealth is allocated in society. Our world has experienced diverging trends, leading to increased prosperity globally, while inequalities remain or increase. Democracies have expanded at the same time that nationalism and protectionism have seen a resurgence. Over the past decades, two major crises have disrupted our societies and weakened our common policy frameworks, casting doubt on our capacity to overcome shocks, address their root causes, and secure a better future for generations to come. They have also reminded us of how interdependent we are.

Our world has experienced diverging trends, leading to increased prosperity globally, while inequalities remain or increase. Democracies have expanded at the same time that nationalism and protectionism have seen a resurgence. Over the past decades, two major crises have disrupted our societies and weakened our common policy frameworks, casting doubt on our capacity to overcome shocks, address their root causes, and secure a better future for generations to come. They have also reminded us of how interdependent we are. I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through.

I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through.