Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

Books about mental illness often reflect on how reality is experienced. In addition to the standard questions — What do we know, and how do we know it? — is another layer of inquiry: What do we know about our own minds, and what if it isn’t true? In her first book, “Brain on Fire,” Susannah Cahalan described her horrifying experience of presenting symptoms of mental illness that looked like schizophrenia but turned out to be an autoimmune disease. She eventually received the treatment she needed, but the tortuous ordeal disrupted her assumptions about the medical profession and her sense of self. Her next project promised to be straightforward by comparison: She would use her skills as an investigative journalist to write about somebody else — a scientist and his pathbreaking study. In 1973, the psychologist David Rosenhan published “On Being Sane in Insane Places” in the journal Science, helping to upend the field of psychiatry. He had recruited healthy volunteers to feign symptoms of mental illness and get admitted to hospitals, thereby showing how easily “sane” people could get institutionalized by a profession that had enormous confidence in its diagnoses and had accumulated a vast amount of power. Cahalan decided to track down these volunteers, or “pseudopatients.” She had landed on a puzzle that seemed to be missing only a few pieces.

Books about mental illness often reflect on how reality is experienced. In addition to the standard questions — What do we know, and how do we know it? — is another layer of inquiry: What do we know about our own minds, and what if it isn’t true? In her first book, “Brain on Fire,” Susannah Cahalan described her horrifying experience of presenting symptoms of mental illness that looked like schizophrenia but turned out to be an autoimmune disease. She eventually received the treatment she needed, but the tortuous ordeal disrupted her assumptions about the medical profession and her sense of self. Her next project promised to be straightforward by comparison: She would use her skills as an investigative journalist to write about somebody else — a scientist and his pathbreaking study. In 1973, the psychologist David Rosenhan published “On Being Sane in Insane Places” in the journal Science, helping to upend the field of psychiatry. He had recruited healthy volunteers to feign symptoms of mental illness and get admitted to hospitals, thereby showing how easily “sane” people could get institutionalized by a profession that had enormous confidence in its diagnoses and had accumulated a vast amount of power. Cahalan decided to track down these volunteers, or “pseudopatients.” She had landed on a puzzle that seemed to be missing only a few pieces.

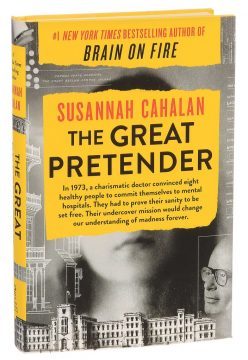

What she unearthed turned out to be far stranger, as documented in her absorbing new book, “The Great Pretender.” It’s the kind of story that has levels to it, only instead of a townhouse it’s more like an Escher print. On one level: A profile of Rosenhan and his study. On another: Cahalan’s own experience of researching the book. And on a third: The fraught history of psychiatry and the pursuit of scientific knowledge.

More here.