Peter Essick in Undark:

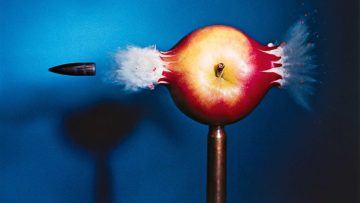

On the evening of Jan. 10, 1957, Harold Edgerton set a 4,000-volt electronic flash of his own design to the right of a small, shallow pool of milk in his “Strobe Lab” at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Edgerton, an electrical engineering professor, then released a drop of milk from a funnel 8 inches above the pool, reflecting a bright red background. A motion trigger was delayed a fraction of a second in order for the powerful flash to record the thumbnail-sized crown of the drop’s splash a few milliseconds after it hit the pool’s surface.

On the evening of Jan. 10, 1957, Harold Edgerton set a 4,000-volt electronic flash of his own design to the right of a small, shallow pool of milk in his “Strobe Lab” at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Edgerton, an electrical engineering professor, then released a drop of milk from a funnel 8 inches above the pool, reflecting a bright red background. A motion trigger was delayed a fraction of a second in order for the powerful flash to record the thumbnail-sized crown of the drop’s splash a few milliseconds after it hit the pool’s surface.

Like any good scientist, Edgerton recorded his data in his notebook. He had first done a successful milk drop photo two decades before in black and white, but kept trying to perfect the shot. His goal was to record equally spaced droplets around the ring. Working with color film that was less sensitive to light made matters more difficult, and when he first saw the color film version of the milk crown, he said it was merely “acceptable” because the droplets were not perfectly spaced. However, to viewers around the world the photo was stunning. In 2016, Time magazine selected “Milk Drop Coronet, 1957” as one of the 100 most influential images of all time, claiming that “the picture proved that photography could advance human understanding of the physical world, and the technology Edgerton used to take it laid the foundation for the modern electronic flash.”

It has been nearly three decades since the death of Edgerton, often called the father of high-speed flash photography. A fresh look at his pioneering work, “Harold Edgerton: Seeing the Unseen,” includes more than 100 photographs and newly released selections from his notebooks, accompanied by essays by former colleagues and curators of the Edgerton photo and strobe archive at the MIT Museum.

More here.