Johnjoe McFadden in Aeon:

Some 2,700 years ago in the ancient city of Sam’al, in what is now modern Turkey, an elderly servant of the king sits in a corner of his house and contemplates the nature of his soul. His name is Katumuwa. He stares at a basalt stele made for him, featuring his own graven portrait together with an inscription in ancient Aramaic. It instructs his family, when he dies, to celebrate ‘a feast at this chamber: a bull for Hadad harpatalli and a ram for Nik-arawas of the hunters and a ram for Shamash, and a ram for Hadad of the vineyards, and a ram for Kubaba, and a ram for my soul that is in this stele.’ Katumuwa believed that he had built a durable stone receptacle for his soul after death. This stele might be one of the earliest written records of dualism: the belief that our conscious mind is located in an immaterial soul or spirit, distinct from the matter of the body.

Some 2,700 years ago in the ancient city of Sam’al, in what is now modern Turkey, an elderly servant of the king sits in a corner of his house and contemplates the nature of his soul. His name is Katumuwa. He stares at a basalt stele made for him, featuring his own graven portrait together with an inscription in ancient Aramaic. It instructs his family, when he dies, to celebrate ‘a feast at this chamber: a bull for Hadad harpatalli and a ram for Nik-arawas of the hunters and a ram for Shamash, and a ram for Hadad of the vineyards, and a ram for Kubaba, and a ram for my soul that is in this stele.’ Katumuwa believed that he had built a durable stone receptacle for his soul after death. This stele might be one of the earliest written records of dualism: the belief that our conscious mind is located in an immaterial soul or spirit, distinct from the matter of the body.

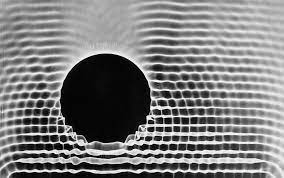

More than 2 millennia later, I was also contemplating the nature of the soul, as my son lay propped up on a hospital gurney. He was undertaking an electroencephalogram (EEG), a test that detects electrical activity in the brain, for a condition that fortunately turned out to be benign. As I watched the irregular wavy lines march across the screen, with spikes provoked by his perceptions of events such as the banging of a door, I wondered at the nature of the consciousness that generated those signals.

Just how do the atoms and molecules that make up the neurons in our brain – not so different to the bits of matter in Katumwa’s inert stele or the steel barriers on my son’s hospital bed – manage to generate human awareness and the power of thought? In answering that longstanding question, most neurobiologists today would point to the information-processing performed by brain neurons. For both Katumuwa and my son, this would begin as soon as light and sound reached their eyes and ears, stimulating their neurons to fire in response to different aspects of their environment. For Katumuwa, perhaps, this might have been the pinecone or comb that his likeness was holding on the stele; for my son, the beeps from the machine or the movement of the clock on the wall.

More here.

It is telling, the entomologist Eleanor Spicer Rice writes in her introduction to a new book of ant photography by Eduard Florin Niga, that humans looking downward on each other from great heights like to describe the miniaturized people we see below us as looking “like ants.” By this we mean faceless, tiny, swarming: an indecipherable mass stripped of individuality or interest. Intellectually, though, we can recognize that each scurrying dot is in fact a unique person with a complicated and interconnected life, even if distance appears to wipe away all that diversity and complexity. So then why, Dr. Rice asks, don’t we apply the same logic to the ants we’re comparing ourselves to?

It is telling, the entomologist Eleanor Spicer Rice writes in her introduction to a new book of ant photography by Eduard Florin Niga, that humans looking downward on each other from great heights like to describe the miniaturized people we see below us as looking “like ants.” By this we mean faceless, tiny, swarming: an indecipherable mass stripped of individuality or interest. Intellectually, though, we can recognize that each scurrying dot is in fact a unique person with a complicated and interconnected life, even if distance appears to wipe away all that diversity and complexity. So then why, Dr. Rice asks, don’t we apply the same logic to the ants we’re comparing ourselves to? Although Wilder père had other plans for his son—a respectable, stable career in the law, an exalted path for good Jewish boys of interwar Vienna—Billie was drawn, almost habitually, to the seductive world of urban and popular culture and to the stories generated and told from within it. “I just fought with my father to become a lawyer,” he recounted for the filmmaker Cameron Crowe in Conversations with Wilder: “That I didn’t want to do, and I saved myself, by having become a newspaperman, a reporter, very badly paid.” As he explains a bit further in the same interview, “I started out with crossword puzzles, and I signed them.” (Toward the end of his life, after having racked up six Academy Awards, Wilder told his German biographer that it wasn’t so much the awards he was most proud of, but rather that his name had appeared twice in the New York Times crossword puzzle: “once 17 across and once 21 down.”)

Although Wilder père had other plans for his son—a respectable, stable career in the law, an exalted path for good Jewish boys of interwar Vienna—Billie was drawn, almost habitually, to the seductive world of urban and popular culture and to the stories generated and told from within it. “I just fought with my father to become a lawyer,” he recounted for the filmmaker Cameron Crowe in Conversations with Wilder: “That I didn’t want to do, and I saved myself, by having become a newspaperman, a reporter, very badly paid.” As he explains a bit further in the same interview, “I started out with crossword puzzles, and I signed them.” (Toward the end of his life, after having racked up six Academy Awards, Wilder told his German biographer that it wasn’t so much the awards he was most proud of, but rather that his name had appeared twice in the New York Times crossword puzzle: “once 17 across and once 21 down.”) I

I  Theroux turns 80 in April. For a generation of backpackers now gone gray, the tattered paperback accounts of his treks through China, Africa and South America were a prod to adventure, bibles of inspiration under many a mosquito net. He has a new novel out from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in April, “Under the Wave at Waimea,” and his best-known book (and

Theroux turns 80 in April. For a generation of backpackers now gone gray, the tattered paperback accounts of his treks through China, Africa and South America were a prod to adventure, bibles of inspiration under many a mosquito net. He has a new novel out from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in April, “Under the Wave at Waimea,” and his best-known book (and

I

I Hungarian-born

Hungarian-born  One would have to be a nihilist, of course, not to wish for an end to a pandemic that has claimed well over two and a half million lives. But for those of us interested in ‘interesting times’, and in the opportunities they open up, the global response to COVID-19 has not been without its political excitements. For the second time in twelve years governments around the world moved to underwrite a system that claims to need no government underwriting, with the result that many of the irrationalities of capitalism were thrown into relief. As incomes withered, or dried up completely, many people came to resent the extent to which their lives were governed by non-productive ownership – by rents and mortgages, principally, the profits from which are hoovered up by a parasitic property system and the financiers who sit atop it. At the same time, the invisible hand of the market was shown to be irrelevant to the needs of a society in crisis, while the speed with which the economy tanked, on the back of a dip in discretionary spending, revealed the basic absurdity of a system predicated on consumer choice.

One would have to be a nihilist, of course, not to wish for an end to a pandemic that has claimed well over two and a half million lives. But for those of us interested in ‘interesting times’, and in the opportunities they open up, the global response to COVID-19 has not been without its political excitements. For the second time in twelve years governments around the world moved to underwrite a system that claims to need no government underwriting, with the result that many of the irrationalities of capitalism were thrown into relief. As incomes withered, or dried up completely, many people came to resent the extent to which their lives were governed by non-productive ownership – by rents and mortgages, principally, the profits from which are hoovered up by a parasitic property system and the financiers who sit atop it. At the same time, the invisible hand of the market was shown to be irrelevant to the needs of a society in crisis, while the speed with which the economy tanked, on the back of a dip in discretionary spending, revealed the basic absurdity of a system predicated on consumer choice. Since 2010, I have been to Guantánamo 13 times. I can’t go as a scholar conducting research or a concerned citizen, so I go as a journalist. When I tell people that I am heading off to Guantánamo, responses tend to range from bafflement to curiosity. Highly educated and politically-aware acquaintances have said things like: “oh, I forgot that place was still open” and “what’s going on there these days?” The symbolic nadir of the US “war on terror” has faded in popular consciousness

Since 2010, I have been to Guantánamo 13 times. I can’t go as a scholar conducting research or a concerned citizen, so I go as a journalist. When I tell people that I am heading off to Guantánamo, responses tend to range from bafflement to curiosity. Highly educated and politically-aware acquaintances have said things like: “oh, I forgot that place was still open” and “what’s going on there these days?” The symbolic nadir of the US “war on terror” has faded in popular consciousness

Alex Hanna, Emily Denton, Razvan Amironesei, Andrew Smart, and Hilary Nicole in Logic:

Alex Hanna, Emily Denton, Razvan Amironesei, Andrew Smart, and Hilary Nicole in Logic: