Category: Recommended Reading

Alan Page Arriaga reads from Six Scripts for Not I

Saturday Poem

I’m a Fool to Love You

Some folks will tell you the blues is a woman,

Some type of supernatural creature.

My mother would tell you, if she could,

About her life with my father,

A strange and sometimes cruel gentleman.

She would tell you about the choices

A young black woman faces.

Is falling in love with the devil

In blue terms, the tongue we use

When we don’t want nuance

To get in the way,

When we need to talk straight?

My mother chooses my father

After choosing a man

Who was, as we sing it,

Of no account.

This made my father look good,

That’s how bad it was.

He made my father seem like an island

In the middle of a stormy sea,

He made my father look like a rock.

And is the blues the moment you realize

You exist in a stacked deck,

You look in a mirror at your young face,

The face my sister carries

And you know it’s the only leverage

You’ve got?

Does this create a hurt that whispers

How you going to do?

Is the blues the moment

You shrug your shoulders

And agree, a girl without money

Is nothing, dust

To be pushed around by any old breeze?

Compared to this,

My father seems, briefly,

To be a fire escape.

This is the way the blues works

Its sorry wonders,

Makes trouble look like

A feather bed,

Makes the wrong man’s kisses

A healing.

by Cornelius Eady

from The Autobiography of a Jukebox

Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1997)

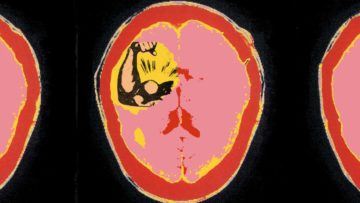

Power Causes Brain Damage

Jerry Useem in The Atlantic:

If power were a prescription drug, it would come with a long list of known side effects. It can intoxicate. It can corrupt. It can even make Henry Kissinger believe that he’s sexually magnetic. But can it cause brain damage? When various lawmakers lit into John Stumpf at a congressional hearing last fall, each seemed to find a fresh way to flay the now-former CEO of Wells Fargo for failing to stop some 5,000 employees from setting up phony accounts for customers. But it was Stumpf’s performance that stood out. Here was a man who had risen to the top of the world’s most valuable bank, yet he seemed utterly unable to read a room. Although he apologized, he didn’t appear chastened or remorseful. Nor did he seem defiant or smug or even insincere. He looked disoriented, like a jet-lagged space traveler just arrived from Planet Stumpf, where deference to him is a natural law and 5,000 a commendably small number. Even the most direct barbs—“You have got to be kidding me” (Sean Duffy of Wisconsin); “I can’t believe some of what I’m hearing here” (Gregory Meeks of New York)—failed to shake him awake.

If power were a prescription drug, it would come with a long list of known side effects. It can intoxicate. It can corrupt. It can even make Henry Kissinger believe that he’s sexually magnetic. But can it cause brain damage? When various lawmakers lit into John Stumpf at a congressional hearing last fall, each seemed to find a fresh way to flay the now-former CEO of Wells Fargo for failing to stop some 5,000 employees from setting up phony accounts for customers. But it was Stumpf’s performance that stood out. Here was a man who had risen to the top of the world’s most valuable bank, yet he seemed utterly unable to read a room. Although he apologized, he didn’t appear chastened or remorseful. Nor did he seem defiant or smug or even insincere. He looked disoriented, like a jet-lagged space traveler just arrived from Planet Stumpf, where deference to him is a natural law and 5,000 a commendably small number. Even the most direct barbs—“You have got to be kidding me” (Sean Duffy of Wisconsin); “I can’t believe some of what I’m hearing here” (Gregory Meeks of New York)—failed to shake him awake.

What was going through Stumpf’s head? New research suggests that the better question may be: What wasn’t going through it?

The historian Henry Adams was being metaphorical, not medical, when he described power as “a sort of tumor that ends by killing the victim’s sympathies.” But that’s not far from where Dacher Keltner, a psychology professor at UC Berkeley, ended up after years of lab and field experiments. Subjects under the influence of power, he found in studies spanning two decades, acted as if they had suffered a traumatic brain injury—becoming more impulsive, less risk-aware, and, crucially, less adept at seeing things from other people’s point of view.

More here.

How Millennials Are Seizing Power and Rewriting the Rules of American Politics

Michael Kazin in The New York Times:

Perhaps the most striking political change that occurred during the stormy reign of Donald J. Trump is one his devotees utterly abhorred: the growth of a sizable left outside and inside the Democratic Party. Young radicals and middle-aged white suburban dwellers both flocked to “the Resistance,” under whose militant rubric one could do anything from marching in a demonstration to starting a Facebook page to canvassing for a favored candidate. During his second run for the White House even more than during his first, Bernie Sanders inspired millions of young people of all races to imagine living in a nation with strong unions and a robust welfare state instead of the “neoliberal” order long favored by leaders of both major parties. And, for many Berniecrats, socialism became the name of their desire instead of a synonym for state tyranny.

Perhaps the most striking political change that occurred during the stormy reign of Donald J. Trump is one his devotees utterly abhorred: the growth of a sizable left outside and inside the Democratic Party. Young radicals and middle-aged white suburban dwellers both flocked to “the Resistance,” under whose militant rubric one could do anything from marching in a demonstration to starting a Facebook page to canvassing for a favored candidate. During his second run for the White House even more than during his first, Bernie Sanders inspired millions of young people of all races to imagine living in a nation with strong unions and a robust welfare state instead of the “neoliberal” order long favored by leaders of both major parties. And, for many Berniecrats, socialism became the name of their desire instead of a synonym for state tyranny.

The journalist David Freedlander’s slim new book, “The AOC Generation,” is a keenly observant narrative, albeit an entirely sympathetic one, about the young women and men most responsible for the upsurge on the left that infused the Democrats with their abundant energy, cleverness and grievances. At the center of his story is Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who may need no introduction but still might blush to read this glowing portrayal by a reporter who lives in her New York City district and appears to have interviewed only people who share his sentiments.

Freedlander calls the congresswoman, who is a wizard of social media, the “avatar of this new generation.” He describes his heroine as an “electric” orator and quotes one of her college friends, who recalls, “Everybody I knew was in love with her.”

More here.

Kim Gordon with Rachel Kushner

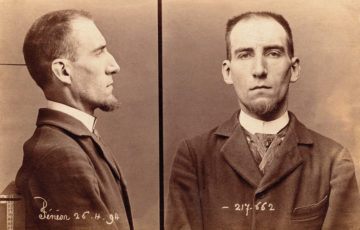

On Félix Fénéon

Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen at Artforum:

The bulk of Fénéon’s art writing has never been translated. For anglophone audiences, he is probably better known for his “Novels in Three Lines,” a litany of more than one thousand mini-tragedies and absurdities published anonymously in 1906 during the half year he spent writing news items for Le Matin, an American-style mass-circulation newspaper founded by a disciple of William Randolph Hearst. These faits divers, of which Luc Sante published an acclaimed translation in 2007, make for reading that is melancholy but piquant. They include random reports such as “On the left shoulder of a newborn, whose corpse was found near the 22nd Artillery barracks, a tattoo: a cannon.” Or: “The sinister prowler seen by the mechanic Gicquel near Herblay train station has been identified: Jules Ménard, snail collector.”

The bulk of Fénéon’s art writing has never been translated. For anglophone audiences, he is probably better known for his “Novels in Three Lines,” a litany of more than one thousand mini-tragedies and absurdities published anonymously in 1906 during the half year he spent writing news items for Le Matin, an American-style mass-circulation newspaper founded by a disciple of William Randolph Hearst. These faits divers, of which Luc Sante published an acclaimed translation in 2007, make for reading that is melancholy but piquant. They include random reports such as “On the left shoulder of a newborn, whose corpse was found near the 22nd Artillery barracks, a tattoo: a cannon.” Or: “The sinister prowler seen by the mechanic Gicquel near Herblay train station has been identified: Jules Ménard, snail collector.”

more here.

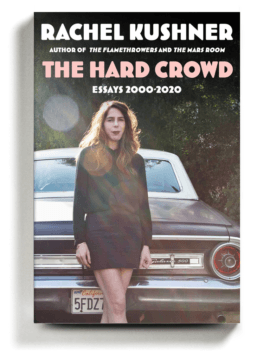

Rachel Kushner’s Essays

Dwight Garner at the New York Times:

Her own motorcycles come to include an orange 500 cc Moto Guzzi, a Kawasaki Ninja and a Cagiva Elefant 650. Her boyfriends tended to be mechanics.

Her own motorcycles come to include an orange 500 cc Moto Guzzi, a Kawasaki Ninja and a Cagiva Elefant 650. Her boyfriends tended to be mechanics.

In what might be this book’s best essay, “Girl on a Motorcycle,” she describes riding the Kawasaki, when she was 24, in the Cabo 1000, a dangerous and illegal 1,000-mile race down the Baja Peninsula, often on unpaved roads.

She describes herself as “kinetic and unfettered and alone.” At one point she hits 142 miles per hour. She is going nearly as fast when another biker pulls out in front of her and she is forced off the road and wipes out. There are predatory ambulances; there are bad Samaritans.

more here.

Friday, April 9, 2021

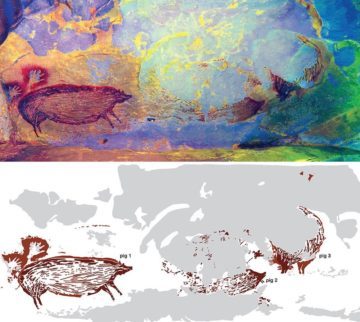

Warty Pig

Morgan Meis at Slant Books:

The warty pig in question is a depiction on the inside of a cave in Indonesia. The painting was discovered last year. It was painted, the carbon daters say, about 45,000 years ago. That’s more than 10,000 years older than the famous paintings at the Chauvet Cave in France. Warty pig is, for now at least, the oldest work of representational art, by far, that exists anywhere in the world. 45,000 years. A long time. Also not a long time, geologically speaking. Just a blip. For us, though, for us, a very long time.

The warty pig in question is a depiction on the inside of a cave in Indonesia. The painting was discovered last year. It was painted, the carbon daters say, about 45,000 years ago. That’s more than 10,000 years older than the famous paintings at the Chauvet Cave in France. Warty pig is, for now at least, the oldest work of representational art, by far, that exists anywhere in the world. 45,000 years. A long time. Also not a long time, geologically speaking. Just a blip. For us, though, for us, a very long time.

Anyway, the painter of warty pig, whoever this person was, seems to have been working on a domestic scene going on between at least three warty pigs. And what might have been the important business amongst the warty pigs on the island of Sulawesi during the forty-fifth-thousand-and-first century BCE? Well, the Sulawesi warty pig lives on the island to this very day. So, we have a pretty good sense of what the pig would have been doing 45,000 years ago. It would have been wandering around in the mornings and early evenings, rooting around in the underbrush looking for goodies to eat. It would have been working out whatever things needed to be worked out in the small social groups in which the pigs tend to live. Maybe that’s what the cave painting is showing us, an impromptu meeting of warty pigs 45,000 years ago. Unfortunately, the images of the other pigs have been lost to us but for a few scraps of color and shape. We’ll never know exactly what was the greater context for this image.

But here are a few things that I love about this fragment that has passed down to us from the deepest recesses of the past.

More here.

Why Bumblebees Love Cats

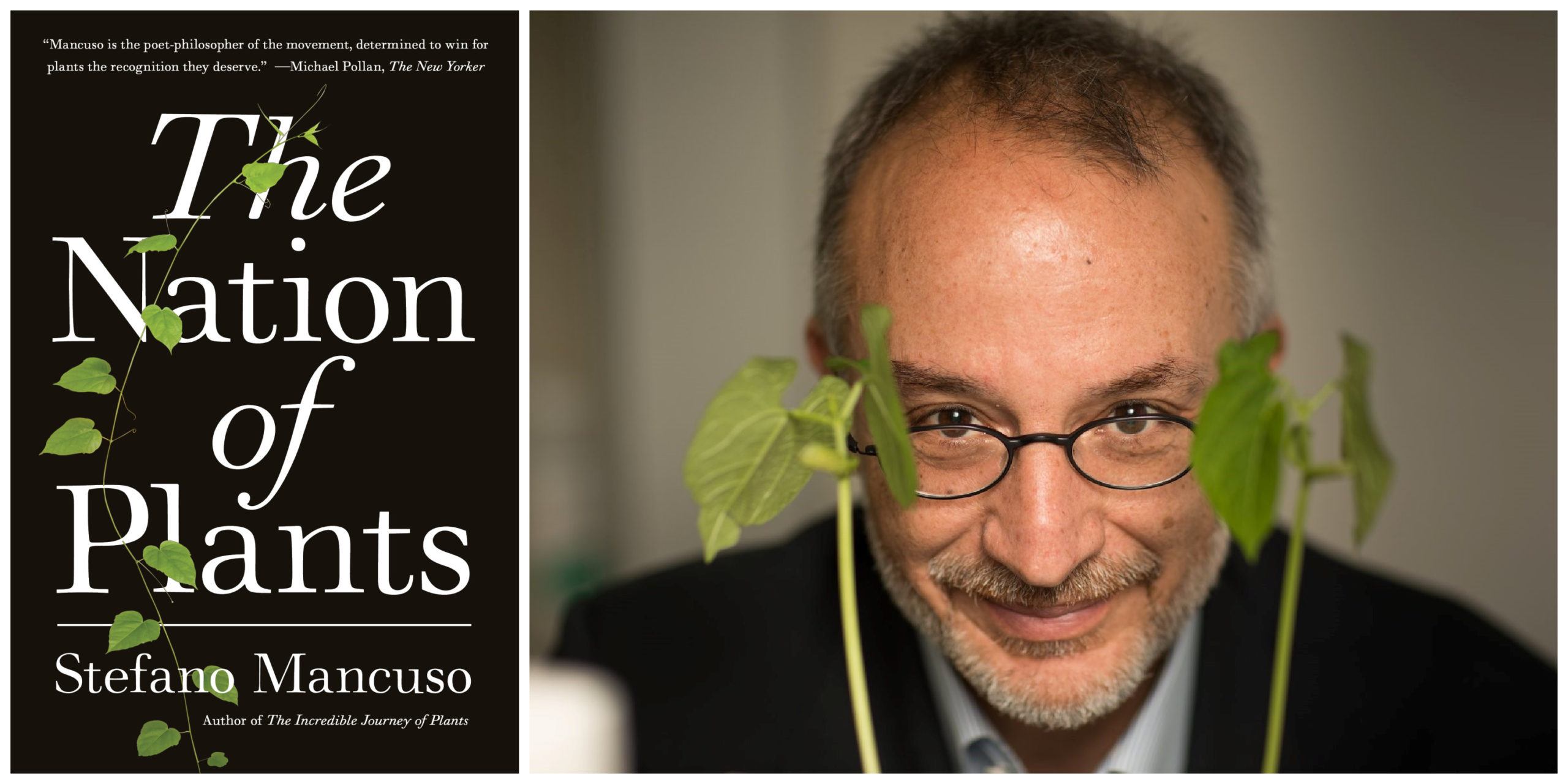

Stefano Mancuso in Longreads:

Darwin writes: what animals could you imagine to be more distant from one another than a cat and a bumblebee? Yet the ties that bind these two animals, though at first glance nonexistent, are on the contrary so strict that were they to be modified, the consequences would be so numerous and profound as to be unimaginable. Mice, argues Darwin, are among the principal enemies of bumblebees. They eat their larvae and destroy their nests. On the other hand, as everyone knows, mice are the favorite prey of cats. One consequence of this is that, in proximity to those villages with the most cats, one finds fewer mice and more bumblebees. So far so clear? Good, let’s go on.

Darwin writes: what animals could you imagine to be more distant from one another than a cat and a bumblebee? Yet the ties that bind these two animals, though at first glance nonexistent, are on the contrary so strict that were they to be modified, the consequences would be so numerous and profound as to be unimaginable. Mice, argues Darwin, are among the principal enemies of bumblebees. They eat their larvae and destroy their nests. On the other hand, as everyone knows, mice are the favorite prey of cats. One consequence of this is that, in proximity to those villages with the most cats, one finds fewer mice and more bumblebees. So far so clear? Good, let’s go on.

Bumblebees are the primary pollinators of many vegetable species, and it is common knowledge that the greater the amount and the quality of pollination the greater the number of seeds produced by the plants. The number and the quality of seeds determines the greater or lesser presence of insects, which, as is well known, are the principal nutriment of numerous bird populations. We could go on like this, adding one group of living species to another, for hours on end: bacteria, fungi, cereals, reptiles, orchids, would succeed one another without pause, one by one, until we ran out of breath, like in those nursery rhymes that connect one event to another without interruption. The ecological relationships that Darwin brings to our attention tell us of a world of bonds much more complex and ungraspable than had ever previously been supposed. Relationships so complex as to connect everything to everything in a single network of the living.

More here. [Thanks to Tony Cobitz.]

Populism is merely a symptom, Treatment must target the underlying disease

Callum Watts in Prospect:

Over the past decade, populism has emerged as an invasive species which has disrupted a previously stable political ecosystem. Liberal democracies across the world have been left in disarray, and occasional victories by establishment parties offer only temporary respite from its onslaught. That is an interpretation that Prospect readers—and all “right-thinking” opinion—will by now have heard many times.

Over the past decade, populism has emerged as an invasive species which has disrupted a previously stable political ecosystem. Liberal democracies across the world have been left in disarray, and occasional victories by establishment parties offer only temporary respite from its onslaught. That is an interpretation that Prospect readers—and all “right-thinking” opinion—will by now have heard many times.

However, in reality, populism is a symptom of the dysfunction, not the cause. It is a corrective response to a political organisation that is already suffering from an underlying pathology. Like many reactions, it can certainly sometimes end up doing more harm than good. But there is no hope in dealing with it decisively—still less of achieving full health to our polity—if the underlying issue isn’t addressed.

To grasp the nature of populism and how to address it, we must first understand what it means to govern well. Opinions will of course differ on the exact criteria. But there would surely be broad support for the inclusion of three qualities: it is legitimate, effective and provident.

More here.

“Seasons” by Future Islands

Friday Poem

Bone of My Bone Flesh of My Flesh

I can’t always refer to the woman I love,

my children’s other mother,

as my darling, my beloved,

sugar in my bowl. No.

I need a common, utilitarian word

that calls no more attention to itself

than nouns like grass, bread, house.

The terms husband and wife are perfect for that.

Hassling with PG&E

or dropping off dry cleaning,

you don’t want to say,

The light of my life doesn’t like starch.

Don’t suggest spouse—a hideous word.

And partner is sterile as a boardroom.

Couldn’t we afford a term

for the woman who carried that girl in her arms

when she was still all promise,

that boy curled inside her womb?

And today, when I go to kiss her

and she says “Not now, I’m reading,”

still she deserves a syllable or two—if only

so I can express how furious

she makes me. But

maybe it’s better this way—

no puny pencil-stub of a word.

Maybe these are exactly the times

to drag out the whole galaxy

of endearments: Buttercup,

I should say, lambkin, mon petit chou.

by Ellen Bass

from The Human Line

Copper Canyon Press, 2007

Bird Photographer of the Year 2021 finalists revealed

From BBC:

The competition, now in its sixth year, provides financial help to grassroots conservation projects through its charity partner Birds on the Brink. “The standard of photography was incredibly high, and the diversity in different species was great to see,” said Will Nicholls, wildlife cameraman and director at BPOTY. “Now the judges are going to have a tough time deciding the winner.” Winners will be announced on 1 September, with the best images to feature in a book published by William Collins. Here is a selection of some of the images from the shortlist, with descriptions by the photographers.

More here.

On Wanting to Change: an inspiring vision of psychoanalysis

Oliver Eagleton in The Guardian:

Those who find writing a chore are better off not knowing about the literary method of Adam Phillips. Every Wednesday he walks to his office in Notting Hill. On this brief journey some idea begins to take shape, usually related to his day job (Phillips is a Freudian psychoanalyst who spends the rest of the week seeing patients). So long as this notion sparks his interest it will – by the time he sits down at his computer – have been transmuted into his first sentence. The next hours are spent unfurling that sentence into an essay, which typically forms part of a collection. Over 30 years this routine has produced almost as many books, in Phillips’s breezy, aphoristic style, on topics ranging from monogamy to sanity to democracy.

Those who find writing a chore are better off not knowing about the literary method of Adam Phillips. Every Wednesday he walks to his office in Notting Hill. On this brief journey some idea begins to take shape, usually related to his day job (Phillips is a Freudian psychoanalyst who spends the rest of the week seeing patients). So long as this notion sparks his interest it will – by the time he sits down at his computer – have been transmuted into his first sentence. The next hours are spent unfurling that sentence into an essay, which typically forms part of a collection. Over 30 years this routine has produced almost as many books, in Phillips’s breezy, aphoristic style, on topics ranging from monogamy to sanity to democracy.

The ease of Phillips’s prose is conditioned by his reluctance to “convince” anyone, including himself. The author treats his readers like his patients, aiming to provoke and stimulate rather than persuade. Yet if psychoanalysis – and psychoanalytic literature – is a discourse concerned with change, how is this achieved without arguing, lecturing or coaxing? Is there a paradigm for altering another person from which coercion is entirely absent? That is the question Phillips poses – with a note of anxiety about his own literary and therapeutic practice – in On Wanting to Change. If there is “something pernicious about the wish to persuade people; or rather to persuade people by disarming them in some way”, then psychoanalysis offers “a form of honest persuasion. Or that, at least, is what it aspires to be.”

“Conversion” is Phillips’s byword for dishonest persuasion. When converted, we experience something akin to regression: helplessness, dependence, over-identification with an all-knowing Other.

More here.

Goya And Suffering

Alejandro Anreus at Commonweal:

In 1792, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) became gravely ill. His convalescence and recovery lasted for more than a year, leaving him completely deaf. (Lead poisoning was suspected.) Had he died right then, at the age of forty-six, Goya would have been remembered as a competent, even elegant, Rococo painter with realist tendencies, but nothing more. Instead, his illness transformed him into an extraordinary artist, one marked by great emotional depth and inventive formal technique.

In 1792, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) became gravely ill. His convalescence and recovery lasted for more than a year, leaving him completely deaf. (Lead poisoning was suspected.) Had he died right then, at the age of forty-six, Goya would have been remembered as a competent, even elegant, Rococo painter with realist tendencies, but nothing more. Instead, his illness transformed him into an extraordinary artist, one marked by great emotional depth and inventive formal technique.

There’s no denying Goya’s prowess as a painter. Just recall his arresting portraits and still lifes, or his masterful frescoes in San Antonio de la Florida Chapel in Madrid. There’s also his powerful Executions of the Third of May 1808 (1814) and his unsettling Black Paintings (1819–23), made near the end of his life. To fully grasp the extent of Goya’s achievements, though, one must consider his drawings and prints.

more here.

Pharoah Sanders Takes on Electronic Music

Hua Hsu at The New Yorker:

Sanders retained a feel for the joyful and raucous immediacy of R. & B. The producer Ed Michel later said, “Pharoah would take an R&B lick and shake it until it vibrated to death, into freedom.” But he soon became a star of the new, experimental wave of sixties jazz, often referred to as the “New Thing” or “free jazz.” At the time, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and others were breaking from traditional approaches to rhythm and harmonic structure. Sanders’s compositions were open and atmospheric, and his playing moved restlessly between smooth, serene melodies and blaring, hyperactive improvisations. You didn’t passively listen to someone like Sanders so much as receive a transference of energy or take in a brilliant explosion of light. Not everyone was ready for it.

Sanders retained a feel for the joyful and raucous immediacy of R. & B. The producer Ed Michel later said, “Pharoah would take an R&B lick and shake it until it vibrated to death, into freedom.” But he soon became a star of the new, experimental wave of sixties jazz, often referred to as the “New Thing” or “free jazz.” At the time, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and others were breaking from traditional approaches to rhythm and harmonic structure. Sanders’s compositions were open and atmospheric, and his playing moved restlessly between smooth, serene melodies and blaring, hyperactive improvisations. You didn’t passively listen to someone like Sanders so much as receive a transference of energy or take in a brilliant explosion of light. Not everyone was ready for it.

more here.

Floating Points, Pharoah Sanders & The London Symphony Orchestra

Thursday, April 8, 2021

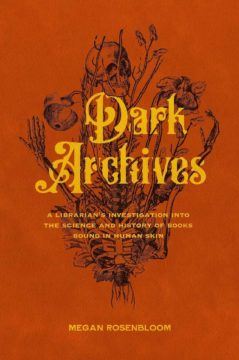

A Look at Anthropodermic Bibliopegy

Christine Jacobson in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

WHEN I FIRST held a book bound in human skin, the little hairs on my neck did not stand up, and chills did not run down my spine. The book looked unremarkable; its pale-yellow binding blended in with its antiquarian neighbors on the shelf. I was holding Des Destinées de l’âme (Destiny of the Soul) by philosopher Arsène Houssaye and standing in the bowels of Houghton Library, Harvard’s rare book and manuscript repository. As a graduate student, I had been hired to truck material between the underground stacks and the reading room, where researchers came from all over the world to pore over the library’s collections. Not long after I arrived, Harvard announced that the 19th-century philosophical treatise I held in my hands was the first proven example using peptide mass fingerprinting of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the practice of binding books in human skin. (Human: anthropos; skin: derma; book: biblion; fasten: pegia.) At my first opportunity, I stole away on a break to get a look at the volume. Holding the book didn’t give me goosebumps, but it did raise many questions. Whose skin was this? What kind of person would bind a book in human skin? And why?

WHEN I FIRST held a book bound in human skin, the little hairs on my neck did not stand up, and chills did not run down my spine. The book looked unremarkable; its pale-yellow binding blended in with its antiquarian neighbors on the shelf. I was holding Des Destinées de l’âme (Destiny of the Soul) by philosopher Arsène Houssaye and standing in the bowels of Houghton Library, Harvard’s rare book and manuscript repository. As a graduate student, I had been hired to truck material between the underground stacks and the reading room, where researchers came from all over the world to pore over the library’s collections. Not long after I arrived, Harvard announced that the 19th-century philosophical treatise I held in my hands was the first proven example using peptide mass fingerprinting of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the practice of binding books in human skin. (Human: anthropos; skin: derma; book: biblion; fasten: pegia.) At my first opportunity, I stole away on a break to get a look at the volume. Holding the book didn’t give me goosebumps, but it did raise many questions. Whose skin was this? What kind of person would bind a book in human skin? And why?

Megan Rosenbloom has spent the last six years pursuing answers to those questions. The results of her efforts are compiled in Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. Readers who relish the “dark academia” vibes of Donna Tartt’s The Secret History or the historical medical accuracy of The Knick will love spending time in Rosenbloom’s company, though the book holds broader appeal as well.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder on the results from the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermilab

Sabine Hossenfelder in Scientific American:

So how are we to gauge the 4.2-sigma discrepancy between the Standard Model’s prediction and the new measurement? First of all, it is helpful to remember the reason that particle physicists use the five-sigma standard to begin with. The reason is not so much that particle physics is somehow intrinsically more precise than other areas of science or that particle physicists are so much better at doing experiments. It’s primarily that particle physicists have a lot of data. And the more data you have, the more likely you are to find random fluctuations that coincidentally look like a signal. Particle physicists began to commonly use the five-sigma criterion in the mid-1990s to save themselves from the embarrassment of having too many “discoveries” that later turn out to be mere statistical fluctuations.

So how are we to gauge the 4.2-sigma discrepancy between the Standard Model’s prediction and the new measurement? First of all, it is helpful to remember the reason that particle physicists use the five-sigma standard to begin with. The reason is not so much that particle physics is somehow intrinsically more precise than other areas of science or that particle physicists are so much better at doing experiments. It’s primarily that particle physicists have a lot of data. And the more data you have, the more likely you are to find random fluctuations that coincidentally look like a signal. Particle physicists began to commonly use the five-sigma criterion in the mid-1990s to save themselves from the embarrassment of having too many “discoveries” that later turn out to be mere statistical fluctuations.

But of course five sigma is an entirely arbitrary cut, and particle physicists also discuss anomalies well below that limit. Indeed, quite a few three- and four-sigma anomalies have come and gone over the years.

More here. [Thanks to Bill Benzon.]