Giles Harvey in The New Yorker:

Few writers have borne witness to the slow-healing bruises of early neglect more memorably than Cynthia Ozick, whose own first novel, “Trust” (1966), didn’t appear until she’d reached the practically geriatric age of thirty-seven. “There one sits, reading and writing, month after month, year after year,” Ozick has said of her long pre-print limbo. “There one sits, envying other young writers who have achieved a grain more than oneself. Without the rush and brush and crush of the world, one becomes hollowed out. The cavity fills with envy.” As it happened, “Trust,” a six-hundred-and-fifty-page homage to Henry James, Ozick’s once and future inspirator, did little to enhance her name recognition. (“Nobody has ever read it,” she said several decades later, only mildly overstating the case.) In the end, it was envy itself that became the means of her literary ascent.

Few writers have borne witness to the slow-healing bruises of early neglect more memorably than Cynthia Ozick, whose own first novel, “Trust” (1966), didn’t appear until she’d reached the practically geriatric age of thirty-seven. “There one sits, reading and writing, month after month, year after year,” Ozick has said of her long pre-print limbo. “There one sits, envying other young writers who have achieved a grain more than oneself. Without the rush and brush and crush of the world, one becomes hollowed out. The cavity fills with envy.” As it happened, “Trust,” a six-hundred-and-fifty-page homage to Henry James, Ozick’s once and future inspirator, did little to enhance her name recognition. (“Nobody has ever read it,” she said several decades later, only mildly overstating the case.) In the end, it was envy itself that became the means of her literary ascent.

…To publish a novel in your early twenties is impressive; to publish one at the age of ninety-three is something else altogether. That is the age that Ozick turns on April 17th, a few days after the publication date of her latest book, which bears the self-ironic title “Antiquities” (Knopf). A brisk work of some thirty thousand words, it explores her favorite subjects—envy and ambition, the moral peril of idolatry—in her favorite form. As you might expect, it also has much to say about last things, and the long perspectives open to the human mind as it approaches its terminus.

“The limitless void that awaits us” is much on the mind of Ozick’s narrator, as well it might be. Lloyd Wilkinson Petrie, a retired lawyer, is getting on in years. It is 1949, and Petrie has come to live at Temple Academy, the esteemed Westchester boarding school he attended in his youth. The school, long defunct, has lately been converted into a retirement home for its trustees, all former pupils. Each has agreed to write a short memoir of his school days as part of a sort of institutional history. What sounds like a harmless exercise in group nostalgia soon takes on an air of the macabre as Petrie’s recollections bring into the light things better left in darkness.

More here.

Efficient folk have come up with a range of productivity techniques. Benjamin Franklin was an early advocate of the modern to-do list. Each morning America’s Founding Father jotted down tasks and asked himself: “What good shall I do this day?” Office grunts take a less virtuous approach to planning. Some practise the Pomodoro technique, a strategy of slicing your day into 25-minute chunks of intense focus with five-minute breaks in between. Many people use a task-management app as a “second brain”, storing their thoughts in the cloud for safekeeping. Productivity tools can also have the opposite effect. You may spend so long managing your time that you never get to the work itself. “Yak shaving” is a term for tasks that lead on to further tasks which distract you from your original goal. If you want to become a time-management master, don’t go anywhere near a yak with a razor.

Efficient folk have come up with a range of productivity techniques. Benjamin Franklin was an early advocate of the modern to-do list. Each morning America’s Founding Father jotted down tasks and asked himself: “What good shall I do this day?” Office grunts take a less virtuous approach to planning. Some practise the Pomodoro technique, a strategy of slicing your day into 25-minute chunks of intense focus with five-minute breaks in between. Many people use a task-management app as a “second brain”, storing their thoughts in the cloud for safekeeping. Productivity tools can also have the opposite effect. You may spend so long managing your time that you never get to the work itself. “Yak shaving” is a term for tasks that lead on to further tasks which distract you from your original goal. If you want to become a time-management master, don’t go anywhere near a yak with a razor. He Jiankui seemed nervous. At the time, he was an obscure researcher working at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China. But he had been working on a top-secret project for the last two years – and he was about to take to the podium at the International Summit on Human Genome Editing to announce the results. There was a general buzz of excitement in the air. The audience looked on anxiously. People started filming on their phones. Jiankui had made the first genetically modified babies in the history of humankind. After 3.7 billion years of continuous, undisturbed evolution by natural selection, a life form had taken its innate biology into its own hands. The result was twin baby girls who were born with altered copies of a gene known as CCR5, which the scientist hoped would make them immune to HIV.

He Jiankui seemed nervous. At the time, he was an obscure researcher working at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China. But he had been working on a top-secret project for the last two years – and he was about to take to the podium at the International Summit on Human Genome Editing to announce the results. There was a general buzz of excitement in the air. The audience looked on anxiously. People started filming on their phones. Jiankui had made the first genetically modified babies in the history of humankind. After 3.7 billion years of continuous, undisturbed evolution by natural selection, a life form had taken its innate biology into its own hands. The result was twin baby girls who were born with altered copies of a gene known as CCR5, which the scientist hoped would make them immune to HIV. DMX CLOSES OUT HIS SONG

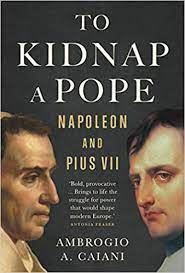

DMX CLOSES OUT HIS SONG This 5 May will mark the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death on St Helena. The occasion will no doubt be marked, as was the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo six years ago, by a flood of new books about the emperor, adding yet more to the estimated 200,000 already written. Given this saturation, one wonders if there is anything left to say. This fascinating book proves that there is. It does so by focusing on a crucial yet neglected aspect of Napoleon’s rule: his bitter, decade-long confrontation with Pope Pius VII. This marked an important step both in the emperor’s decline and fall, and in the evolution of the Catholic Church.

This 5 May will mark the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death on St Helena. The occasion will no doubt be marked, as was the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo six years ago, by a flood of new books about the emperor, adding yet more to the estimated 200,000 already written. Given this saturation, one wonders if there is anything left to say. This fascinating book proves that there is. It does so by focusing on a crucial yet neglected aspect of Napoleon’s rule: his bitter, decade-long confrontation with Pope Pius VII. This marked an important step both in the emperor’s decline and fall, and in the evolution of the Catholic Church. Catherine Menon was born in Perth, Western Australia, where her British mother and Malaysian father met. She lectures in robotics and has a PhD in pure mathematics as well as an MA in creative writing. Fragile Monsters, her first novel, is set in rural Malaysia and unpicks a family’s story from 1920 to the present day. At its centre are Mary, “sharp tongued and ferocious”, and her visiting granddaughter, Durga, who tussle over the demons and dark memories that distort their past and warp the present. Hilary Mantel has described Menon’s writing as “supple, artful, skilful storytelling” and she has won awards for her short stories. She is married to a fellow mathematician and lives in north London.

Catherine Menon was born in Perth, Western Australia, where her British mother and Malaysian father met. She lectures in robotics and has a PhD in pure mathematics as well as an MA in creative writing. Fragile Monsters, her first novel, is set in rural Malaysia and unpicks a family’s story from 1920 to the present day. At its centre are Mary, “sharp tongued and ferocious”, and her visiting granddaughter, Durga, who tussle over the demons and dark memories that distort their past and warp the present. Hilary Mantel has described Menon’s writing as “supple, artful, skilful storytelling” and she has won awards for her short stories. She is married to a fellow mathematician and lives in north London. A massive landslide—the worst in decades—struck Du Fangming’s home in south China’s Hunan province on July 6. “My house collapsed. My goats were swept away by the mud,” he told Chinese media outlets shortly after the catastrophe. Fortunately, though, he was safe—one of 33 villagers who had been evacuated thanks to early warnings enabled by advanced positioning technologies that can provide more accurate readings than ever before.

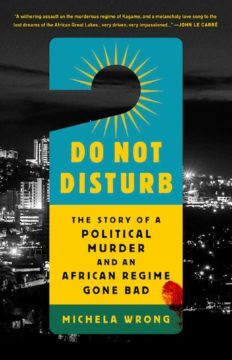

A massive landslide—the worst in decades—struck Du Fangming’s home in south China’s Hunan province on July 6. “My house collapsed. My goats were swept away by the mud,” he told Chinese media outlets shortly after the catastrophe. Fortunately, though, he was safe—one of 33 villagers who had been evacuated thanks to early warnings enabled by advanced positioning technologies that can provide more accurate readings than ever before. In the view of most historians, the original sin of Rwanda came from the colonial policy of making artificial ethnic distinctions through a caste-like system. Belgian administrators deemed those who were taller and herded cattle, the Tutsis, to be smarter than the Hutu, who were generally shorter and raised crops. So one group got all the privileges of helping the Belgians extract coffee and animal hides and were treated as sub-royals, while their countrymen were deemed slow and stupid. The story was fixed; the Goods and Bads had been preselected, and the inevitable resentments would explode in the 1994 genocide.

In the view of most historians, the original sin of Rwanda came from the colonial policy of making artificial ethnic distinctions through a caste-like system. Belgian administrators deemed those who were taller and herded cattle, the Tutsis, to be smarter than the Hutu, who were generally shorter and raised crops. So one group got all the privileges of helping the Belgians extract coffee and animal hides and were treated as sub-royals, while their countrymen were deemed slow and stupid. The story was fixed; the Goods and Bads had been preselected, and the inevitable resentments would explode in the 1994 genocide. WHAT IS THE POINT

WHAT IS THE POINT  Few writers have borne witness to the slow-healing bruises of early neglect more memorably than Cynthia Ozick, whose own first novel, “

Few writers have borne witness to the slow-healing bruises of early neglect more memorably than Cynthia Ozick, whose own first novel, “ Alissa Wilkinson in Vox:

Alissa Wilkinson in Vox: David Barsamian interviews Noam Chomsky in Boston Review:

David Barsamian interviews Noam Chomsky in Boston Review: