Achin Vanaik in Jacobin:

The ongoing struggle of farmers in India is the most significant mass mobilization in decades and represents the biggest challenge to the government of Narendra Modi since it first came to power in 2014.

The three agricultural reform laws forced through Parliament during the pandemic lockdown provoked this wave of protest. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) insists that those laws are necessary to modernize an archaic and outdated system of farm production. Farmers, however, rightly see the dismantling of regulations, price controls, and public procurement commitments as a threat to their livelihoods.

They fear that opening up the sector to corporate agribusinesses and financial interests will lead to greater polarization of landholdings. This in turn will cause a large-scale displacement of farmers and laborers into an informal sector that already accounts for more than 90 percent of the total workforce and is incapable of providing enough employment or renumeration.

A Second Wind

Since late November 2020, hundreds of thousands of farmers, mainly from Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh, have camped on the outskirts of Delhi, disrupting the main roads into the capital. Rejecting the government’s offers to temporarily suspend the new laws, they have remained steadfast in demanding their repeal.

More here.

Adam Tooze in the LRB:

Adam Tooze in the LRB: Robert Kuttner in the New York Review of Books:

Robert Kuttner in the New York Review of Books: Carlos Sardina Galache in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Carlos Sardina Galache in the NLR’s Sidecar: Dániel Oláh in Evonomics:

Dániel Oláh in Evonomics: Growing up, I never saw my Korean-American parents touch each other. No hugs or kisses, or even pats on the back. It wasn’t the byproduct of a loveless marriage, just the consequences of a life centered on survival — that endless list of unsexy chores. I’ve lived 30 years without acknowledging such biographical details, accepting that the nuances of my life could never make it into mainstream culture.

Growing up, I never saw my Korean-American parents touch each other. No hugs or kisses, or even pats on the back. It wasn’t the byproduct of a loveless marriage, just the consequences of a life centered on survival — that endless list of unsexy chores. I’ve lived 30 years without acknowledging such biographical details, accepting that the nuances of my life could never make it into mainstream culture. When we talk, we naturally gesture—we open our palms, we point, we chop the air for emphasis. Such movement may be more than superfluous hand flapping. It helps communicate ideas to listeners and even appears to help speakers think and learn. A growing field of psychological research is exploring the potential of having students or teachers gesture as pupils learn. Studies have shown that people remember material better when they make spontaneous gestures, watch a teacher’s movements or use their hands and arms to imitate the instructor. More recent work suggests that telling learners to move in specific ways can help them learn—even when they are unaware of why they are making the motions.

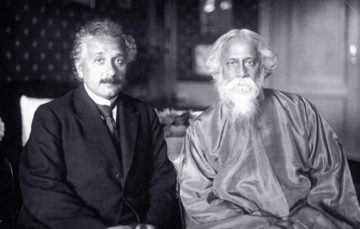

When we talk, we naturally gesture—we open our palms, we point, we chop the air for emphasis. Such movement may be more than superfluous hand flapping. It helps communicate ideas to listeners and even appears to help speakers think and learn. A growing field of psychological research is exploring the potential of having students or teachers gesture as pupils learn. Studies have shown that people remember material better when they make spontaneous gestures, watch a teacher’s movements or use their hands and arms to imitate the instructor. More recent work suggests that telling learners to move in specific ways can help them learn—even when they are unaware of why they are making the motions. Rabindranath Tagore, who died in 1941 at the age of eighty, is a towering figure in the millennium-old literature of Bengal. Anyone who becomes familiar with this large and flourishing tradition will be impressed by the power of Tagore’s presence in Bangladesh and in India. His poetry as well as his novels, short stories, and essays are very widely read, and the songs he composed reverberate around the eastern part of India and throughout Bangladesh.

Rabindranath Tagore, who died in 1941 at the age of eighty, is a towering figure in the millennium-old literature of Bengal. Anyone who becomes familiar with this large and flourishing tradition will be impressed by the power of Tagore’s presence in Bangladesh and in India. His poetry as well as his novels, short stories, and essays are very widely read, and the songs he composed reverberate around the eastern part of India and throughout Bangladesh. During every waking moment, we humans and other animals have to balance on the edge of our awareness of past and present. We must absorb new sensory information about the world around us while holding on to short-term memories of earlier observations or events. Our ability to make sense of our surroundings, to learn, to act and to think all depend on constant, nimble interactions between perception and memory.

During every waking moment, we humans and other animals have to balance on the edge of our awareness of past and present. We must absorb new sensory information about the world around us while holding on to short-term memories of earlier observations or events. Our ability to make sense of our surroundings, to learn, to act and to think all depend on constant, nimble interactions between perception and memory. The British spy agency GCHQ is so aggressive, extreme and unconstrained by law or ethics that the NSA — not exactly world renowned for its restraint — often farms out spying activities too scandalous or illegal for the NSA to their eager British counterparts. There is, as the Snowden

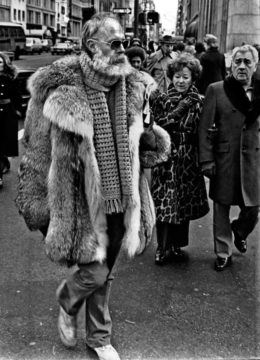

The British spy agency GCHQ is so aggressive, extreme and unconstrained by law or ethics that the NSA — not exactly world renowned for its restraint — often farms out spying activities too scandalous or illegal for the NSA to their eager British counterparts. There is, as the Snowden  Gorey favored huge fur coats paired with jeans, sweaters, sneakers, and ever-present small gold hoops in each ear. His constantly-donned coats earned him a 1978 write-up in the New York Times titled “

Gorey favored huge fur coats paired with jeans, sweaters, sneakers, and ever-present small gold hoops in each ear. His constantly-donned coats earned him a 1978 write-up in the New York Times titled “ One of the most vacuous idioms we use about our moral and social debates is the idea of being “on the side of history”. The plain meaning of this is that “history” – the record of human actions – has an inevitable trajectory, and we had better get on board with it or suffer the consequences.

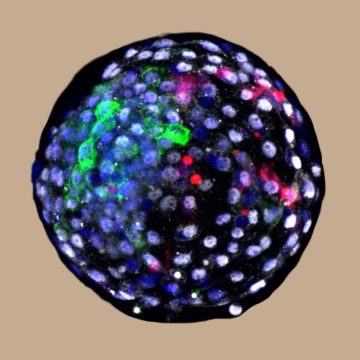

One of the most vacuous idioms we use about our moral and social debates is the idea of being “on the side of history”. The plain meaning of this is that “history” – the record of human actions – has an inevitable trajectory, and we had better get on board with it or suffer the consequences. Scientists have successfully grown monkey embryos containing human cells for the first time — the latest milestone in a rapidly advancing field that has drawn ethical questions.

Scientists have successfully grown monkey embryos containing human cells for the first time — the latest milestone in a rapidly advancing field that has drawn ethical questions. I

I Long before the advent of non-fungible tokens, some advocates of digital art argued that there is no meaningful distinction between a “virtual” object and a “physical” one. Such a division, they believed, partakes of the fallacy of “digital dualism,” the imprecise belief that a file is somehow less “real” than a painting on canvas, when in fact both are products of mind and time accreted to the permanence of matter. Less arty or newfangled is the old law of property. A contract is a ghost story for adults: It turns vaporous whatevers—labor time, carbon, pixel—into a coin struck by the handshake of exchange and the creep of law. Ownership was always a song and a dance and a fusillade.

Long before the advent of non-fungible tokens, some advocates of digital art argued that there is no meaningful distinction between a “virtual” object and a “physical” one. Such a division, they believed, partakes of the fallacy of “digital dualism,” the imprecise belief that a file is somehow less “real” than a painting on canvas, when in fact both are products of mind and time accreted to the permanence of matter. Less arty or newfangled is the old law of property. A contract is a ghost story for adults: It turns vaporous whatevers—labor time, carbon, pixel—into a coin struck by the handshake of exchange and the creep of law. Ownership was always a song and a dance and a fusillade. A team of Egyptian archaeologists

A team of Egyptian archaeologists