Dilip Hiro in The Nation:

Dilip Hiro in The Nation:

Like his immediate predecessor, Joe Biden is committed to a distinctly anti-China global strategy and has sworn that China will not “become the leading country in the world, the wealthiest country in the world, and the most powerful country in the world…on my watch.” In the topsy-turvy universe created by the Covid-19 pandemic, it was, however, Jamie Dimon, the CEO and chairman of JP Morgan Chase, a banking giant with assets of $3.4 trillion, who spoke truth to Biden on the subject.

While predicting an immediate boom in the US economy “that could easily run into 2023,” Dimon had grimmer news on the future as well. “China’s leaders believe that America is in decline,” he wrote in his annual letter to the company’s shareholders. While the United States had faced tough times in the past, he added, today “the Chinese see an America that is losing ground in technology, infrastructure, and education—a nation torn and crippled by politics, as well as racial and income inequality—and a country unable to coordinate government policies (fiscal, monetary, industrial, regulatory) in any coherent way to accomplish national goals.” He was forthright enough to say, “Unfortunately, recently, there is a lot of truth to this.”

As for China, Dimon could also have added, its government possesses at least two powerful levers in areas where the United States is likely to prove vulnerable: dominant control of container ports worldwide and the supplies of rare earth metals critical not just to the information-technology sector but also to the production of electric and hybrid cars, jet fighters, and missile guidance systems.

More here.

Philip Roth

Philip Roth Seth Rogen’s home sits on several wooded acres in the hills above Los Angeles, under a canopy of live oak and eucalyptus trees strung with outdoor pendants that light up around dusk, when the frogs on the grounds start croaking. I pulled up at the front gate on a recent afternoon, and Rogen’s voice rumbled through the intercom. “Hellooo!” He met me at the bottom of his driveway, which is long and steep enough that he keeps a golf cart up top “for schlepping big things up the driveway that are too heavy to walk,” he said, adding, as if bashful about coming off like the kind of guy who owns a dedicated driveway golf cart, “It doesn’t get a ton of use.” Rogen wore a beard, chinos, a cardigan from the Japanese brand Needles and Birkenstocks with marled socks — laid-back Canyon chic. He led me to a switchback trail cut into a hillside, which we climbed to a vista point. Below us was Rogen’s office; the house he shares with his wife, Lauren, and their 11-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Zelda; and the converted garage where they make pottery. I was one of the first people, it turns out, to see the place. “I haven’t had many people over,” Rogen said, “because we moved in during the pandemic.”

Seth Rogen’s home sits on several wooded acres in the hills above Los Angeles, under a canopy of live oak and eucalyptus trees strung with outdoor pendants that light up around dusk, when the frogs on the grounds start croaking. I pulled up at the front gate on a recent afternoon, and Rogen’s voice rumbled through the intercom. “Hellooo!” He met me at the bottom of his driveway, which is long and steep enough that he keeps a golf cart up top “for schlepping big things up the driveway that are too heavy to walk,” he said, adding, as if bashful about coming off like the kind of guy who owns a dedicated driveway golf cart, “It doesn’t get a ton of use.” Rogen wore a beard, chinos, a cardigan from the Japanese brand Needles and Birkenstocks with marled socks — laid-back Canyon chic. He led me to a switchback trail cut into a hillside, which we climbed to a vista point. Below us was Rogen’s office; the house he shares with his wife, Lauren, and their 11-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Zelda; and the converted garage where they make pottery. I was one of the first people, it turns out, to see the place. “I haven’t had many people over,” Rogen said, “because we moved in during the pandemic.” It is always tricky writing about Kipling. By the time of his death in 1936 his jingoism, with its babble about the “white man’s burden” in Africa, made many moderate souls feel queasy. Batchelor is too scrupulous a scholar to ignore what came after the Just So Stories – indeed he points out that within two years of the book’s publication the satirist Max Beerbohm was drawing Kipling as an imperial stooge, the diminutive bugle-blowing cockney lover of a blousy-looking Britannia.

It is always tricky writing about Kipling. By the time of his death in 1936 his jingoism, with its babble about the “white man’s burden” in Africa, made many moderate souls feel queasy. Batchelor is too scrupulous a scholar to ignore what came after the Just So Stories – indeed he points out that within two years of the book’s publication the satirist Max Beerbohm was drawing Kipling as an imperial stooge, the diminutive bugle-blowing cockney lover of a blousy-looking Britannia. The evenhanded approach of

The evenhanded approach of  I thought I was so clever. For a few days, anyway.

I thought I was so clever. For a few days, anyway. The first numbers that come to mind when thinking about Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland might be how much money the movie is raking in at the box office.

The first numbers that come to mind when thinking about Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland might be how much money the movie is raking in at the box office. I would like to stage a fight between two different accounts of the current political landscape—what’s been called the “post-truth” era, the infodemic, the end of democracy, or perhaps most accurately, the total shitshow of the now.

I would like to stage a fight between two different accounts of the current political landscape—what’s been called the “post-truth” era, the infodemic, the end of democracy, or perhaps most accurately, the total shitshow of the now. “W

“W “It feels like a grew a new heart.” That’s what my best friend told me the day her daughter was born. Back then, I rolled my eyes at her new-mom corniness. But ten years and three kids of my own later, Emily’s words drift back to me as I ride a crammed elevator up to a laboratory in New York City’s

“It feels like a grew a new heart.” That’s what my best friend told me the day her daughter was born. Back then, I rolled my eyes at her new-mom corniness. But ten years and three kids of my own later, Emily’s words drift back to me as I ride a crammed elevator up to a laboratory in New York City’s  A

A  With the vanishing of the name goes the disappearance of the object, the slice of art, the fragment of literature, the portion of music. With the fading of the thing, so the name is gradually effaced from memory, and whatever there was becomes anonymous.

With the vanishing of the name goes the disappearance of the object, the slice of art, the fragment of literature, the portion of music. With the fading of the thing, so the name is gradually effaced from memory, and whatever there was becomes anonymous.

In his previous essay collection,

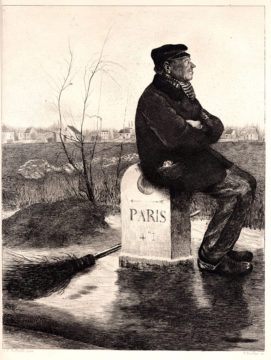

In his previous essay collection,  Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless.

Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless.