Category: Recommended Reading

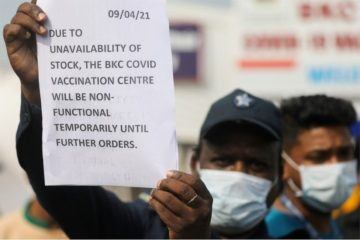

Covid-19: How India failed to prevent a deadly second wave

Soutik Biswas at the BBC:

In less than a month, things began to unravel. India was in the grips of a devastating second wave of the virus and cities were facing fresh lockdowns. By mid-April, the country was averaging more than 100,000 cases a day. On Sunday, India recorded more than 270,000 cases and over 1,600 deaths, both new single-day records. If the runway infection was not checked, India could be recording more than 2,300 deaths every day by first week of June, according to a report by The Lancet Covid-19 Commission.

In less than a month, things began to unravel. India was in the grips of a devastating second wave of the virus and cities were facing fresh lockdowns. By mid-April, the country was averaging more than 100,000 cases a day. On Sunday, India recorded more than 270,000 cases and over 1,600 deaths, both new single-day records. If the runway infection was not checked, India could be recording more than 2,300 deaths every day by first week of June, according to a report by The Lancet Covid-19 Commission.

India is in now in the grips of a public health emergency. Social media feeds are full with videos of Covid funerals at crowded cemeteries, wailing relatives of the dead outside hospitals, long queues of ambulances carrying gasping patients, mortuaries overflowing with the dead, and patients, sometimes two to a bed, in corridors and lobbies of hospitals. There are frantic calls for help for beds, medicines, oxygen, essential drugs and tests. Drugs are being sold on the black market, and test results are taking days. “They didn’t tell me for three hours that my child is dead,” a dazed mother says in one video, sitting outside an ICU. Wails of another person outside the intensive care punctuate the silences.

More here.

Richard Linklater Presents: Summer (Le Rayon Vert)

On ‘The Tarot of Leonora Carrington’

Chloe Wyma at Artforum:

Carrington made The High Priestess, one of only two cards to have been dated, in 1955, around the same time she and her friend Remedios Varo were haunting the metaphysical clubs established by the disciples of Russian mystics P. D. Ouspensky and G. I. Gurdjieff. Esoterica had long been fashionable in Mexico City. Diego Rivera, when called on by the Communist Party in 1954 to justify his membership in the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, said the group was “essentially materialist.” But Carrington and Varo’s occultism was especially committed, prodigious, and syncretic, encompassing tarot, alchemy, witchcraft, Kabbalah, and indigenous Mexican magic and healing practices. Carrington’s library included at least thirteen titles on cartomancy by authors including Ouspensky, A. E. Waite, Joseph Oswald Wirth, and her friend Kurt Seligmann (who reportedly fell out with André Breton after correcting his interpretation of a tarot card). A March 1943 issue of the Surrealist journal VVV records, alongside Carrington’s recipe for stuffed beef in sherry wine, her aborted attempt with Roberto Matta to invent a new divinatory system that would be to tarot “what non-Euclidian geometry is to Euclidian geometry.”

Carrington made The High Priestess, one of only two cards to have been dated, in 1955, around the same time she and her friend Remedios Varo were haunting the metaphysical clubs established by the disciples of Russian mystics P. D. Ouspensky and G. I. Gurdjieff. Esoterica had long been fashionable in Mexico City. Diego Rivera, when called on by the Communist Party in 1954 to justify his membership in the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, said the group was “essentially materialist.” But Carrington and Varo’s occultism was especially committed, prodigious, and syncretic, encompassing tarot, alchemy, witchcraft, Kabbalah, and indigenous Mexican magic and healing practices. Carrington’s library included at least thirteen titles on cartomancy by authors including Ouspensky, A. E. Waite, Joseph Oswald Wirth, and her friend Kurt Seligmann (who reportedly fell out with André Breton after correcting his interpretation of a tarot card). A March 1943 issue of the Surrealist journal VVV records, alongside Carrington’s recipe for stuffed beef in sherry wine, her aborted attempt with Roberto Matta to invent a new divinatory system that would be to tarot “what non-Euclidian geometry is to Euclidian geometry.”

more here.

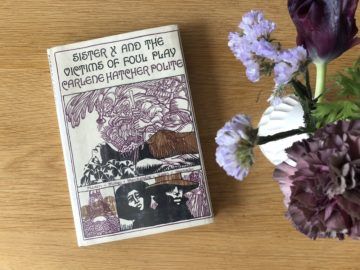

The Novel as a Long Alto Saxophone Solo

Lucy Scholes at The Paris Review:

The Flagellants, the American writer Carlene Hatcher Polite’s debut novel, is one of those out-of-print books that’s been lurking in the corner of my eye for the past few years. First published by Christian Bourgois éditeur as Les Flagellants in Pierre Alien’s 1966 French translation, and then in its original English the following year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the book details the stormy relationship between Ideal and Jimson, a Black couple in New York City. The narrative is largely made up of a series of stream of consciousness orations. Polite’s prose is frenetic and loquacious, and her characters fling both physical and verbal violence back and forth across the page. The French edition received much praise. Polite was deemed “a poet of the weird, an angel of the bizarre,” and the novel was described as “so haunting, so rich in thoughts, sensations, so well located in a poetic chiaroscuro that one [could] savor its ineffaceable harshness.” And while certain American critics weren’t so impressed—“Miss Polite’s narrative creaks with the stresses of literary uncertainty,” wrote Frederic Raphael in the New York Times, summing the novel up as a “dialectical diatribe”—others recognized this young Black woman’s singular, if still rather raw and emergent, talent. Malcolm Boyd, for example, declared the novel “a work of lush imagery and exciting semantic exploration.” It won Polite—then in her midthirties and living in Paris with the youngest of her two daughters—fellowships from the National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities (1967) and the Rockefeller Foundation (1968).

The Flagellants, the American writer Carlene Hatcher Polite’s debut novel, is one of those out-of-print books that’s been lurking in the corner of my eye for the past few years. First published by Christian Bourgois éditeur as Les Flagellants in Pierre Alien’s 1966 French translation, and then in its original English the following year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the book details the stormy relationship between Ideal and Jimson, a Black couple in New York City. The narrative is largely made up of a series of stream of consciousness orations. Polite’s prose is frenetic and loquacious, and her characters fling both physical and verbal violence back and forth across the page. The French edition received much praise. Polite was deemed “a poet of the weird, an angel of the bizarre,” and the novel was described as “so haunting, so rich in thoughts, sensations, so well located in a poetic chiaroscuro that one [could] savor its ineffaceable harshness.” And while certain American critics weren’t so impressed—“Miss Polite’s narrative creaks with the stresses of literary uncertainty,” wrote Frederic Raphael in the New York Times, summing the novel up as a “dialectical diatribe”—others recognized this young Black woman’s singular, if still rather raw and emergent, talent. Malcolm Boyd, for example, declared the novel “a work of lush imagery and exciting semantic exploration.” It won Polite—then in her midthirties and living in Paris with the youngest of her two daughters—fellowships from the National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities (1967) and the Rockefeller Foundation (1968).

more here.

Tuesday Poem

.

What is my life worth? At the end (I don’t know what end)

One person says: I earned three hundred contos,

Another: I enjoyed three thousand days of glory,

Another: I was at ease with my conscience and that is enough…

And I, if they come and ask me what I have done,

Will say: I looked at things, nothing more.

And that is why I have the Universe here in my pocket.

And f God asks me: And what did you see in those things?

I will answer: Only things … You yourself added nothing else.

And God, who despite all is clever, will make me a new kind of

………. saint.

by Fernando Pessoa

from The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro

New Directions Paperbook, 2020

translated from the Portuguese by

…Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari

Conto: a former money of account in Portugal and Brazil

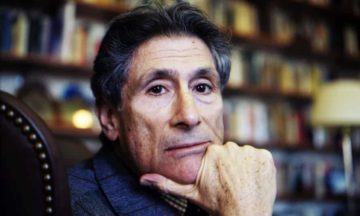

Places of Mind – a generous and heartfelt biography of Edward Said

Ahdaf Soueif in The Guardian:

Long after his death in 2003, Edward W Said remains a partner in many imaginary conversations.” The opening line of Tim Brennan’s biography of Said is true – it’s hard to come up with another thinker who remains so present in his absence. Some 50 or so books have been written about him. His writings are taught in universities across the world. Look on social media and you’ll find him constantly referred to, in easy, familiar terms, by the young across the globe. His portrait is on the walls of the old cities of Palestine, in the company of the martyrs. The events of the past years, not least the Arab uprisings and the counter-revolutionary triumphs that followed them, have been for many of us occasions where we turned to his ideas and his example.

Long after his death in 2003, Edward W Said remains a partner in many imaginary conversations.” The opening line of Tim Brennan’s biography of Said is true – it’s hard to come up with another thinker who remains so present in his absence. Some 50 or so books have been written about him. His writings are taught in universities across the world. Look on social media and you’ll find him constantly referred to, in easy, familiar terms, by the young across the globe. His portrait is on the walls of the old cities of Palestine, in the company of the martyrs. The events of the past years, not least the Arab uprisings and the counter-revolutionary triumphs that followed them, have been for many of us occasions where we turned to his ideas and his example.

Said bestrode not just one world, but several. Just as he was at the same moment a New Yorker and a Palestinian brought up in Egypt, he was also a literary critic, a theorist, a political activist, a musician and more. And if this led to him being “not quite right” in any one world, his genius was to transmute this condition into the engine of ideas around which a considerable part of the intellectual and political life of these worlds came to revolve.

Brennan was Said’s student and friend, familiar with his ideas and comfortable in his company. For Places of Mind he worked closely with Said’s family, conducted interviews with a wide range of his friends and colleagues and (he must have) thoroughly mined the archive held in Columbia University, where Said taught for his entire career. (One delightful moment in the book is when Brennan finds that Said’s teaching notes from 1964 to 1984 prove his old teacher’s statement that some of his best ideas came from his teaching.)

More here.

Lift off! First flight on Mars launches new way to explore worlds

Alexandra Witze in Nature:

NASA has pulled off the first powered flight on another world. Ingenuity, the robot rotorcraft that is part of the agency’s Perseverance mission, lifted off from the surface of Mars on 19 April, in a 39.1-second flight that is a landmark in interplanetary aviation. “We can now say that human beings have flown a rotorcraft on another planet,” says MiMi Aung, the project’s lead engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

NASA has pulled off the first powered flight on another world. Ingenuity, the robot rotorcraft that is part of the agency’s Perseverance mission, lifted off from the surface of Mars on 19 April, in a 39.1-second flight that is a landmark in interplanetary aviation. “We can now say that human beings have flown a rotorcraft on another planet,” says MiMi Aung, the project’s lead engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Ingenuity’s short test flight is the off-Earth equivalent of the Wright Brothers piloting their aeroplane above the coastal dunes at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903. In tribute, the helicopter carries a postage-stamp-sized piece of muslin fabric from the Wright Brothers’ plane. “Each world gets only one first flight,” says Aung.

The flight came after a one-week delay, because software issues kept the helicopter from transitioning into flight mode two days ahead of a planned flight attempt on 11 April. Today, at 12:34 a.m. US Pacific time, Ingenuity successfully spun its counter-rotating carbon-fibre blades at more than 2,400 revolutions per minute to give it the lift it needed to rise 3 metres into the air. The US$85-million drone hovered there, and then, in a planned manoeuvre, turned 96 degrees and descended safely back to the Martian surface. “This is just the first great flight,” says Aung.

More here.

Sunday, April 18, 2021

The Digital Revolution Is Eating Its Young

Mark Esposito, Landry Signé, and Nicholas Davis in Project Syndicate:

As massive online platforms have given rise to numerous virtual marketplaces, a gap has opened between the real and the digital economy. And by driving more people than ever online in search of goods, services, and employment, the coronavirus pandemic is widening it. The risk now is that a new digital industrial complex will hamper market efficiency by imposing rents on real-economy players whose daily operations depend on technology.

The premise of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) is that the tangible and intangible elements of today’s economy can coexist and create new productive synergies. The tangible side of the economy provides the infrastructure upon which automation, manufacturing, and complex trade networks rest, and intangibles – logistics, communication, and other software and Big Data applications – allow for these processes to achieve optimal efficiency.

More to the point, the tangible economy is a prerequisite for the intangible economy. Through digitalization, tangibles can become intangibles and then overcome traditional limitations on scale and value creation. While heavily transactional and capital-intensive, this process hitherto has been a positive mechanism for growth, providing some equity of opportunities for small and large countries alike.

But this standard account of the 4IR omits the recent decoupling of the digital and real sectors of the economy.

More here.

First GMO Mosquitoes to Be Released In the Florida Keys

Taylor White in Undark:

This spring, the biotechnology company Oxitec plans to release genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes in the Florida Keys. Oxitec says its technology will combat dengue fever, a potentially life-threatening disease, and other mosquito-borne viruses — such as Zika — mainly transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

While there have been more than 7,300 dengue cases reported in the United States between 2010 and 2020, a majority are contracted in Asia and the Caribbean, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Florida, however, there were 41 travel-related cases in 2020, compared with 71 cases that were transmitted locally.

Native mosquitoes in Florida are increasingly resistant to the most common form of control — insecticide — and scientists say they need new and better techniques to control the insects and the diseases they carry. “There aren’t any other tools that we have. Mosquito nets don’t work. Vaccines are under development but need to be fully efficacious,” says Michael Bonsall, a mathematical biologist at the University of Oxford, who is not affiliated with Oxitec but has collaborated with the company in the past, and who worked with the World Health Organization to produce a GM mosquito-testing framework.

Bonsall and other scientists think a combination of approaches is essential to reducing the burden of diseases — and that, maybe, newer ideas like GM mosquitoes should be added to the mix. Oxitec’s mosquitoes, for instance, are genetically altered to pass what the company calls “self-limiting” genes to their offspring; when released GM males breed with wild female mosquitoes, the resulting generation does not survive into adulthood, reducing the overall population.

More here.

The Unbearable Burden of Invention: Imitation, once the foundation of creativity in architecture, is banished

Witold Rybczynski in The Hedgehog Review:

Buildings’ nicknames are the public’s attempt to make sense of the incomprehensible. Several odd-looking London skyscrapers have cheekily illustrative monikers: the Gherkin, the Cheesegrater, the Walkie-Talkie. Angelenos call the mammoth Pacific Design Center the Blue Whale. Beijingites offhandedly refer to the headquarters of China Central Television as Big Underpants. A Shanghai skyscraper with an aperture at the top is the Bottle Opener, and Bilbao has the Artichoke, Frank Gehry’s titanium Guggenheim museum. My favorite is the nickname of an addition to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam—the Bathtub.

Buildings’ nicknames are the public’s attempt to make sense of the incomprehensible. Several odd-looking London skyscrapers have cheekily illustrative monikers: the Gherkin, the Cheesegrater, the Walkie-Talkie. Angelenos call the mammoth Pacific Design Center the Blue Whale. Beijingites offhandedly refer to the headquarters of China Central Television as Big Underpants. A Shanghai skyscraper with an aperture at the top is the Bottle Opener, and Bilbao has the Artichoke, Frank Gehry’s titanium Guggenheim museum. My favorite is the nickname of an addition to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam—the Bathtub.

The original Stedelijk Museum, or city museum, was built in 1895 in the style of the sixteenth-century Dutch Renaissance. The gingerbread red-brick building with pale stone stripes is pretty as a picture. The 2012 modern addition, which doubled the size of the museum, is the work of the Amsterdam architectural firm Benthem Crouwel. The competition-winning design ignores its neighbor and obviously aspires to be the Dutch equivalent of the Bilbao Guggenheim, an in-your-face architectural icon. From certain angles, the windowless white form, raised in the air and covered in a reinforced synthetic fiber finished in glossy white paint, really does resemble a giant hot tub. Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times observed that “entering an oversize plumbing fixture to commune with classic modern art is like hearing Bach played by a man wearing a clown suit.” Not good.

More here.

Negative Space: Close Reading Trauma Porn

Maya Gurantz in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Buy me a drink and I’ll break down for you my new obsession: the abuse documentary. It’s a new genre, it’s everywhere on streaming media, and I’ve watched them all.

Buy me a drink and I’ll break down for you my new obsession: the abuse documentary. It’s a new genre, it’s everywhere on streaming media, and I’ve watched them all.

I can describe the precise differences between Part I of Surviving R. Kelly and Part II: The Reckoning; at precisely what point the second half of the series The Keepers loses its initial unrelenting momentum; what makes Lorena, about the Bobbitt case, best of genre; what makes On the Record, about music executive Russell Simmons, peak #MeToo; how Leaving Neverland, the four-hour-long two-parter about Michael Jackson’s pedophilia is critically enhanced by the coda of the Oprah Winfrey-hosted, talk show-format After Neverland; why Seduced, about Keith Raniere and the NXIVM cult, is an abuse doc; why The Vow, about Keith Raniere and the NXIVM cult, isn’t; why the two separate Jeffrey Epstein series (Surviving Jeffrey Epstein and Jeffrey Epstein Filthy Rich) both oddly feel like we’re jumping the shark a bit; and how two Larry Nassar documentaries, At the Heart of Gold and Athlete A, can hit so many identical beats while coming to such entirely different conclusions. You might think I’ve fallen behind this past month, what with the release of the four-part Allen v Farrow and the 8-episode CBC Podcast Evil by Design (about Peter Nygard, the “Canadian Jeffrey Epstein”), but don’t you worry. I’m all caught up.

How did the unraveling of serial sexual abuse become a blockbuster genre? What constitutes its formal newness, on the one hand, and its connection to a rich lineage of American sentimental storytelling about women’s injury on the other?

More here.

Sunday Poem

Summer

Winter is cold-hearted,

Spring is yea and nay,

Autumn is a weathercock

Blown every way.

Summer days for me

When every leaf is on its tree;

When Robin’s not a beggar,

And Jenny Wren’s a bride,

And larks hang singing, singing, singing,

Over the wheat-fields wide,

And anchored lilies ride,

And the pendulum spider

Swings from side to side;

And blue-black beetles transact business,

And gnats fly in a host,

And furry caterpillars hasten

That no time be lost,

And moths grow fat and thrive,

And ladybirds arrive.

Before green apples blush,

Before green nuts embrown,

Why one day in the country

Is worth a month in town;

Is worth a day and a year

Of the dusty, musty, lag-last fashion

That days drone elsewhere.

by Christina Rossetti

from the National Poetry Library

If life exists on other planets, we’ll find the words

Melissa Mohr in The Christian Science Monitor:

In February, the rover Perseverance arrived on Mars after an almost eight-month journey, tasked with looking for signs of ancient life. Though no firm evidence of life beyond Earth has yet been found, the English language is already full of words to talk about it. The search for life on other planets is part of the science of astrobiology. The prefix astro- is “star” in Latin and Greek and, predictably, appears in astronomy, the study of objects beyond the Earth’s atmosphere.

In February, the rover Perseverance arrived on Mars after an almost eight-month journey, tasked with looking for signs of ancient life. Though no firm evidence of life beyond Earth has yet been found, the English language is already full of words to talk about it. The search for life on other planets is part of the science of astrobiology. The prefix astro- is “star” in Latin and Greek and, predictably, appears in astronomy, the study of objects beyond the Earth’s atmosphere.

Astrobiologists aren’t just looking for microbes on Mars. They are also trying to predict what life might look like under conditions vastly different from those on Earth. Physicists Luis Anchordoqui and Eugene Chudnovsky speculate that there might be life inside stars, for example. Hypothetical particles called magnetic monopoles might assemble into chains and 3D structures, and be able to replicate by using energy from the star’s fusion. This is not “life as we know it,” to misquote “Star Trek,” but these particle chains would be “alive” at least by some definitions. A group of astrobiologists has proposed a term that would more obviously include “creatures” like these, so unlike anything found on Earth: lyfe. Lyfe (pronounced “loife”) is a broader category that would encourage scientists to think outside the box, to “open [them]selves up to exploring the full parameter space of physical and chemical interactions that may create life,” write Stuart Bartlett and Michael Wong.

More here.

Mary Ellen Moylan (1925 – 2020)

Rusty Young (1946 – 2021)

Benita Raphan (1962 – 2021)

Prometheus’ Toolbox

Adrienne Mayor in Lapham’s Quarterly:

How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans.

How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans.

Prometheus was first introduced in Hesiod’s poems, written between 750 and 650 bc, and about two dozen Greek and Latin writers retold and embellished his story. From earliest times Prometheus was seen as the benefactor of primitive humankind. One familiar rendering of the Prometheus myth was featured in the Athenian tragedy Prometheus Bound, attributed to Aeschylus, circa 460 bc. The play opens with the blacksmith god Hephaestus reluctantly chaining Prometheus to a rock at the end of the world. The chorus asks Prometheus why he is being punished. “I gave humans hope,” he replies, “so they may be optimistic, and taught them the secrets of fire, from which they may learn many crafts and arts (technai).”

But fire was the sacred possession of the immortals, and Zeus, the tyrannical king of the gods, took harsh revenge on Prometheus for stealing fire for the benefit of mere mortals, sending an eagle to gnaw eternally at his liver. The technology of fire gave humans some autonomy from their divine creators—now they could invent language, plan cooperatively, make tools, protect themselves from the elements and from each other, and increasingly manipulate the world around them according to their own desires. In time Prometheus’ gifts were expanded to include writing, mathematics, medicine, agriculture, domestication of animals, mining, science—in other words, all the arts of civilization. We might say that by giving men and women this basic technology, Prometheus opened the door for humans—themselves products of divine biotechne—to begin engaging in their own biotechne.

By the fifth century bc, the Athenians were venerating the rebel Prometheus and his precious gifts of fire and technology alongside the city’s favorite gods, Athena and Hephaestus.

More here.

Saturday, April 17, 2021

Wilhelm Reich: The Strange, Prescient Sexologist

Olivia Laing at The Guardian:

What Reich wanted to understand was the body itself: why you might want to escape or subdue it, why it remains a naked source of power. His wild life draws together aspects of bodily experience that remain intensely relevant now, from illness to sex, anti-fascist direct action to incarceration. The writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin read Reich, as did many of the second-wave feminists. Susan Sontag wrote Illness As Metaphor as a riposte to his theories about health, while Kate Bush’s song “Cloudbusting” immortalises his battle with the law, its insistent, hiccupping refrain – “I just know that something good is going to happen” – conveying the compelling utopian atmosphere of his ideas.

What Reich wanted to understand was the body itself: why you might want to escape or subdue it, why it remains a naked source of power. His wild life draws together aspects of bodily experience that remain intensely relevant now, from illness to sex, anti-fascist direct action to incarceration. The writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin read Reich, as did many of the second-wave feminists. Susan Sontag wrote Illness As Metaphor as a riposte to his theories about health, while Kate Bush’s song “Cloudbusting” immortalises his battle with the law, its insistent, hiccupping refrain – “I just know that something good is going to happen” – conveying the compelling utopian atmosphere of his ideas.

Reich believed that the emotional and the political directly impact our bodily experience, and he also thought that both realms could be improved, that Eden could even at this late juncture be retrieved. He was vilified in his own era, sometimes for good reason, but many of his ideas still hum and wriggle with life.

more here.

The Brief, Brilliant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry

Parul Sehgal at the NYT:

The curtain rises on a dim, drab room. An alarm sounds, and a woman wakes. She tries to rouse her sleeping child and husband, calling out: “Get up!”

The curtain rises on a dim, drab room. An alarm sounds, and a woman wakes. She tries to rouse her sleeping child and husband, calling out: “Get up!”

It is the opening scene — and the injunction — of Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play “A Raisin in the Sun,” the story of a Black family living on the South Side of Chicago. “Never before, in the entire history of the American theater, had so much of the truth of Black people’s lives been seen on the stage,” her friend James Baldwin would later recall. It was the first play by a Black woman to be produced on Broadway. When “Raisin” won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle award for best play, Hansberry — at 29 — became the youngest American and the first Black recipient.

more here.