Category: Recommended Reading

Memories of Murder: In the Killing Jar

Ed Park at The Current:

In September 2019, about halfway between claiming the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May and earning multiple Oscar nominations in January 2020, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite was briefly upstaged by a movie from the director’s past. His second feature, Memories of Murder (2003), had grappled with South Korea’s most chilling cold case: a spree in which ten women and girls were raped and murdered near Hwaseong, about twenty-six miles south of Seoul. (Song Kang Ho, a star of Parasite, plays one of the police detectives obsessed with nabbing the culprit.) According to a May 2020 CNN story, “About 226,000 people lived in the area, scattered among a number of villages between forested hills and rice paddies,” in a region that previously had reported “no real crime to speak of.” The slaughter began in 1986 and continued for five years. A suspect was jailed for one of the crimes in 1989 and released on parole in 2009; the others, however, went unanswered. The specter of what have been called Korea’s first serial killings profoundly spooked the nation: Police investigated over 20,000 people, some even after the statute of limitations expired in 2006. Over two million “man-days” were devoted to the case—nearly 5,500 years, longer by a millennium than Korea itself has been around. You could think of the investigation as an entire civilization built around a singular depravity.

In September 2019, about halfway between claiming the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May and earning multiple Oscar nominations in January 2020, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite was briefly upstaged by a movie from the director’s past. His second feature, Memories of Murder (2003), had grappled with South Korea’s most chilling cold case: a spree in which ten women and girls were raped and murdered near Hwaseong, about twenty-six miles south of Seoul. (Song Kang Ho, a star of Parasite, plays one of the police detectives obsessed with nabbing the culprit.) According to a May 2020 CNN story, “About 226,000 people lived in the area, scattered among a number of villages between forested hills and rice paddies,” in a region that previously had reported “no real crime to speak of.” The slaughter began in 1986 and continued for five years. A suspect was jailed for one of the crimes in 1989 and released on parole in 2009; the others, however, went unanswered. The specter of what have been called Korea’s first serial killings profoundly spooked the nation: Police investigated over 20,000 people, some even after the statute of limitations expired in 2006. Over two million “man-days” were devoted to the case—nearly 5,500 years, longer by a millennium than Korea itself has been around. You could think of the investigation as an entire civilization built around a singular depravity.

more here.

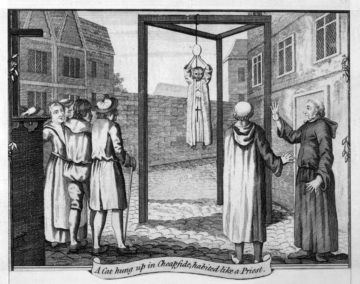

Animals On Trial

Jeffrey Kastner at Cabinet Magazine:

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.2 Yet for all the import (both practical and metaphysical) of the issues on which they touch, in their details the tales Evans spins often seem to suggest nothing so much as a series of lost Monty Python sketches—from the story of the distinguished 16th-century French jurist Bartholomew Chassenée, who was said to have made his not inconsiderable reputation for creative argument and persistent advocacy on the strength of his representation of “some rats, which had been put on trial before the ecclesiastical court of Autun on the charge of having feloniously eaten up and wantonly destroyed the barley crop of that province,”3 to the 1750 trial in Vanvres of a “she-ass, taken in the act of coition” with one Jacques Ferron. In the latter case, the unfortunate quadruped was sentenced to death along with her seducer and appeared headed for the gallows until a last minute reprieve was issued on behalf of the parish priest and citizenry of the village, who had “signed a certificate stating that they had known the said she-ass for four years, and that she had always shown herself to be virtuous and well-behaved both at home and abroad and had never given occasion of scandal to anyone…” Nudge, nudge; say no more.

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.2 Yet for all the import (both practical and metaphysical) of the issues on which they touch, in their details the tales Evans spins often seem to suggest nothing so much as a series of lost Monty Python sketches—from the story of the distinguished 16th-century French jurist Bartholomew Chassenée, who was said to have made his not inconsiderable reputation for creative argument and persistent advocacy on the strength of his representation of “some rats, which had been put on trial before the ecclesiastical court of Autun on the charge of having feloniously eaten up and wantonly destroyed the barley crop of that province,”3 to the 1750 trial in Vanvres of a “she-ass, taken in the act of coition” with one Jacques Ferron. In the latter case, the unfortunate quadruped was sentenced to death along with her seducer and appeared headed for the gallows until a last minute reprieve was issued on behalf of the parish priest and citizenry of the village, who had “signed a certificate stating that they had known the said she-ass for four years, and that she had always shown herself to be virtuous and well-behaved both at home and abroad and had never given occasion of scandal to anyone…” Nudge, nudge; say no more.

more here.

Sunday, May 2, 2021

The Neoliberal Fantasy at the Heart of ‘Nomadland’

Arun Gupta and Michelle Fawcett in In These Times:

In the real world, many nomads desperately want a house. One admits “there is not so much difference between” the van dweller and the homeless person. By making Fern’s story one of personal responsibility and freedom, the movie erases the causes of the nomads’ economic pain. Individual suffering becomes individual triumph; the crisis of capitalism is also the solution.

In the real world, many nomads desperately want a house. One admits “there is not so much difference between” the van dweller and the homeless person. By making Fern’s story one of personal responsibility and freedom, the movie erases the causes of the nomads’ economic pain. Individual suffering becomes individual triumph; the crisis of capitalism is also the solution.

If nomads are refugees from the subprime mortgage crash, the perilous landscape they travel was shaped by the tectonic social upheavals that began in the Reagan era. Fern’s exile from Empire, owned by a gypsum-mining company, is a nod to the deindustrialization that accelerated under Reagan. The landscape of permanent homelessness that nomads exist in was born of Reagan gutting funds for social welfare and cities. Nomads trade leads on jobs flipping burgers at tourist spots and cleaning toilets in national parks like they trade can openers for potholders at desert meetups. Gig work is another Reagan-era legacy; his assault on organized labor made it easier for corporations to expand contingent labor.

In the film, Amazon becomes as natural as the land. Wide-angle shots of the Amazon warehouse make it appear to rise up like the mountains in the Nevada desert. It is a neutral feature on the terrain that one can only navigate, not change.

More here.

How to Rewrite the Laws of Physics in the Language of Impossibility

Amanda Gefter in Quanta:

They say that in art, constraints lead to creativity. The same seems to be true of the universe. By placing limits on nature, the laws of physics squeeze out reality’s most fantastical creations. Limit light’s speed, and suddenly space can shrink, time can slow. Limit the ability to divide energy into infinitely small units, and the full weirdness of quantum mechanics blossoms. “Declaring something impossible leads to more things being possible,” writes the physicist Chiara Marletto. “Bizarre as it may seem, it is commonplace in quantum physics.”

They say that in art, constraints lead to creativity. The same seems to be true of the universe. By placing limits on nature, the laws of physics squeeze out reality’s most fantastical creations. Limit light’s speed, and suddenly space can shrink, time can slow. Limit the ability to divide energy into infinitely small units, and the full weirdness of quantum mechanics blossoms. “Declaring something impossible leads to more things being possible,” writes the physicist Chiara Marletto. “Bizarre as it may seem, it is commonplace in quantum physics.”

Marletto grew up in Turin, in northern Italy, and studied physical engineering and theoretical physics before completing her doctorate at the University of Oxford, where she became interested in quantum information and theoretical biology. But her life changed when she attended a talk by David Deutsch, another Oxford physicist and a pioneer in the field of quantum computation. It was about what he claimed was a radical new theory of explanations. It was called constructor theory, and according to Deutsch it would serve as a kind of meta-theory more fundamental than even our most foundational physics — deeper than general relativity, subtler than quantum mechanics. To call it ambitious would be a massive understatement.

More here.

How the N-Word Became Unsayable

John McWhorter in the New York Times:

This article contains obscenities and racial slurs, fully spelled out. Ezekiel Kweku, the Opinion politics editor, and Kathleen Kingsbury, the Opinion editor, wrote about how and why we came to the decision to publish these words in Friday’s edition of the Opinion Today newsletter.

This article contains obscenities and racial slurs, fully spelled out. Ezekiel Kweku, the Opinion politics editor, and Kathleen Kingsbury, the Opinion editor, wrote about how and why we came to the decision to publish these words in Friday’s edition of the Opinion Today newsletter.

In 1934, Allen Walker Read, an etymologist and lexicographer, laid out the history of the word that, then, had “the deepest stigma of any in the language.” In the entire article, in line with the strength of the taboo he was referring to, he never actually wrote the word itself. The obscenity to which he referred, “fuck,” though not used in polite company (or, typically, in this newspaper), is no longer verboten. These days, there are two other words that an American writer would treat as Mr. Read did. One is “cunt,” and the other is “nigger.” The latter, though, has become more than a slur. It has become taboo.

Just writing the word here, I sense myself as pushing the envelope, even though I am Black — and feel a need to state that for the sake of clarity and concision, I will be writing the word freely, rather than “the N-word.” I will not use the word gratuitously, but that will nevertheless leave a great many times I do spell it out, love it though I shall not.

More here.

When Men Behave Badly: The Hidden Roots of Sexual Deception, Harassment, and Assault

Rob Henderson in Quillette:

Professor David M. Buss, a leading evolutionary psychologist, states in the introduction of his fascinating new book that it “uncovers the hidden roots of sexual conflict.” Though the book focuses on male misbehavior, it also contains a broad and fascinating overview of mating psychology.

Professor David M. Buss, a leading evolutionary psychologist, states in the introduction of his fascinating new book that it “uncovers the hidden roots of sexual conflict.” Though the book focuses on male misbehavior, it also contains a broad and fascinating overview of mating psychology.

Sex, as defined by biologists, is indicated by the size of our gametes. Males have smaller gametes (sperm) and females have larger gametes (eggs). Broadly speaking, women and men had conflicting interests in the ancestral environment. Women were more vulnerable than men. And women took on far more risk when having sex, including pregnancy, which was perilous in an environment without modern technology. In addition to the physical costs, in the final stages of pregnancy, women must also obtain extra calories. According to Britain’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, pregnant women in their final trimester require an additional 200 calories per day, or 18,000 calories more in total than they otherwise would have required. This surplus was not easy to obtain for our ancestors. Men, in contrast, did not face the same level of sexual risk.

More here.

Christa Ludwig (1928 – 2021)

Jill Corey (1935 – 2021)

Bob Fass (1933 – 2021)

Sunday Poem

And Applaud

Once a young man came to me and said,

Dear Master,

I am feeling strong and brave today,

And I would like to know the truth

About all of my —attachments.

And I replied,

Attachments?

Attachments!

Sweet Heart,

Do you really want me to speak to you

About all your attachments,

When I can see so clearly

You have built, with so much care,

Such a great brothel

To house all of your pleasures.

You have even surrounded the whole damn place

With armed guards and vicious dogs

To protect your desires

So that you can sneak away

From time to time

And try to squeeze light

Into your parched being

From a source as fruitful

As a dried date pit

That even a bird

Is wise enough to spit out.

Your attachments! My dear,

Let’s not speak of those,

For Hafiz knows

The torments and agonies

That every mind on the way to Annihilation in the sun

Must endure.

So at night in my prayers I often stop

And ask a thousand angels to join in

And applaud

Anything

Anything in this world

That can bring your heart comfort.

by Hafiz

rendition by Daniel Ladinsky

from I Heard God Laughing

Penguin Books, 2006

Democracy Requests the Pleasure of Your Company

Doris Sommer in Harvard Magazine:

THE DAY BEFORE she cast two tiebreaker votes in the Senate in early February, Vice President Kamala Harris brought chocolates for senators on both sides of the aisle and then huddled with a few senior members around a fire in her office. The gestures were no doubt strategic, given her determination to support progressive decisions, but they also conjure references to another period of social gatherings hosted by elegant women. It was during the Enlightenment, when such gatherings in private salons outside the royal palaces softened the absolutist culture of European monarchies.

THE DAY BEFORE she cast two tiebreaker votes in the Senate in early February, Vice President Kamala Harris brought chocolates for senators on both sides of the aisle and then huddled with a few senior members around a fire in her office. The gestures were no doubt strategic, given her determination to support progressive decisions, but they also conjure references to another period of social gatherings hosted by elegant women. It was during the Enlightenment, when such gatherings in private salons outside the royal palaces softened the absolutist culture of European monarchies.

From the seventeenth century on, spirited conversation in salons became a favorite pastime for educated noblemen and a burgeoning class of professionals, sundry guests who could exercise the wit and curiosity that they acquired through humanistic education. In the welcoming atmosphere of private homes, where hostesses presided with social grace to stimulate lively but not contentious conversation, gentlemen got together with businessmen, military leaders, diplomats, poets, and philosophers to talk about a range of topics that often had no apparent practical or moral value. Disinterested sparring made social equality thinkable. Diverse guests recognized one another as worthy interlocutors. Conversation across class differences depended on talking about fascinating things that didn’t rely on privilege or expertise. They talked about beauty, for example, precisely because it has no established criteria and depends on personal, subjective, responses that people want to share in inter-subjective judgments, to take Immanuel Kant’s line of thinking. When conversations veered toward interests in politics and economics, an alert hostess would tactfully steer the speakers back to the safer space of exciting but uncontentious sparring about the arts.

Aesthetics is the name of this egalitarian activity, a social venture that follows from being surprised by something beautiful, or even something ugly. The surprise is visceral and stays subjective, but the experience—when we think and talk about it—is social. Extended engagement with beauty or the sublime has no practical purpose beyond the pleasure of engaging. This shared pause from pursuits is an obvious and available antidote to the crush of self-interested calculation and competition.

More here.

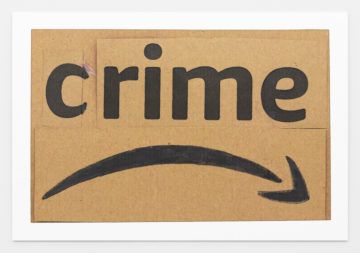

Prime Mover: Amazon’s role in American inequality

Alex Press in Bookforum:

GET BIG FAST was an early Amazon motto. The slogan sounds like a fratty refrain tossed around at the gym. Jeff Bezos had it printed on T-shirts. More than twenty-five years after leaving his position as a Wall Street hedge-fund executive to found Amazon, Bezos’s size anxiety is long gone. (At least as it pertains to his company; the CEO’s Washington, DC, house has eleven bedrooms and twenty-five bathrooms, a bedroom-to-bathroom ratio that raises both architectural and scatological questions.) Bezos is now worth $180 billion. Amazon, were it a country, would have a larger GDP than Australia.

GET BIG FAST was an early Amazon motto. The slogan sounds like a fratty refrain tossed around at the gym. Jeff Bezos had it printed on T-shirts. More than twenty-five years after leaving his position as a Wall Street hedge-fund executive to found Amazon, Bezos’s size anxiety is long gone. (At least as it pertains to his company; the CEO’s Washington, DC, house has eleven bedrooms and twenty-five bathrooms, a bedroom-to-bathroom ratio that raises both architectural and scatological questions.) Bezos is now worth $180 billion. Amazon, were it a country, would have a larger GDP than Australia.

Such numbers are nonsensically large—there’s no way to make them stick. But in 2017, Bezos demonstrated what they mean. That was the year the company conducted a nationwide sweepstakes to choose a location for its second headquarters, or HQ2, as it was called. Seattle was already a company town: Amazon had more than 40,000 employees there, and as much of the city’s office space as the next forty largest employers combined. It was time to take over a new city.

Local and state governments raced to undercut each other. It wasn’t only tax credits that in some locations amounted to over $1 billion; the subsidies offered to Amazon were a display of abject creativity. Bezos is a Trekkie, so Chicago had Star Trek star William Shatner narrate the city’s pitch video. Tucson, Arizona, sent a giant saguaro cactus to Amazon headquarters. Sly James, Kansas City’s mayor at the time, bought and reviewed one thousand Amazon products, giving every item five stars. But the locations Bezos selected—New York City and Northern Virginia—were always going to win. Together, the chosen bids gave the company over $3 billion in tax incentives and grants.

More here.

Saturday, May 1, 2021

The Woman Who Shattered the Myth of the Free Market

Zachary D. Carter in the New York Times:

Zachary D. Carter in the New York Times:

When Joan Robinson arrived at Cambridge University in 1929, nobody expected her to become one of the most important economists of the 20th century — let alone the 21st. She had spent the past three of her nearly 26 years in India, where she lived without professional responsibilities while her husband, Austin, an economist six years her senior, tutored a child maharajah. When Austin returned to Britain to join the Cambridge economics faculty, Joan, who had studied the subject as an undergraduate, felt her own ambitions kindled. But she had entered an environment hostile to women.

For 40 years, economics at Cambridge had been dominated by Alfred Marshall, whose intellectual achievements were rivaled only by his misogyny. He’d married Mary Paley, the first woman to lecture in economics at the university, and then promptly destroyed her career, pulling her book out of print. Marshall, a frustrated Robinson noted, treated his wife as a “housekeeper and a secretary.”

But Robinson would avenge her most emphatically. She would go on to devise a new theory that upended Marshall’s intellectual legacy, radically altering our understanding of the relationship between competition and labor power. Now those ideological innovations are shaping the revived debate over antitrust reform.

More here.

Science Doesn’t Work That Way

Gregory Kaebnick in Boston Review:

Gregory Kaebnick in Boston Review:

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to take every public problem—vast social inequality, political polarization, the spread of conspiracy theories—and magnify it. Among these problems is the public’s growing distrust of scientists and other experts. As Archon Fung, a scholar of democratic governance at Harvard’s Kennedy School, has put it, the U.S. public is in a “wide-aperture, low-deference” mood: deeply disinclined to recognize the authority of traditional leaders, scientists among them, on a wide range of topics—including masks and social distancing.

As the world continues to struggle through waves of disease, many seek a world more inclined to listen to scientific experts. But getting there does not require returning to the high-deference attitude the public may have once held toward experts. Turning back the clock may well be both impossible and undesirable. In a way, a low-deference stance toward experts and authorities is just what a well-functioning democracy aims at.

There is a deep puzzle here for science and policy-making. Complete rejection of expertise not only makes little epistemic sense (for there is no doubt that expertise exists); the complexities of the modern state make trust in others’ expertise indispensable. On the other hand, unqualified deference to those in positions of power and privilege vitiates the basic principles of democracy.

How do we reconcile these facts?

More here.

Thinking About the Intersection Between Human Rights and the Arts

Katie Kheriji-Watts in Hyperallergic:

Katie Kheriji-Watts in Hyperallergic:

The artist Tania El Khoury has written that she is “on a constant quest to find political meaning in the artistic form.” Her installations and performances — many of which are collaborative, interactive, and site specific — have focused on a wide range of subjects, including the refugee experience, state violence, and the long history of power outages in her home country of Lebanon. She groups her multifaceted work under the label of “live art,” which the Live Art Development Agency describes as a framing device (rather than an art form or discipline) for a wide variety of experiences that embody new ways of thinking about “what art is, what it can do, and where and how it can be experienced.”

In early 2021, El Khoury and her partner, the historian Ziad Abu-Rish, relocated from Beirut to New York’s Hudson Valley to jointly spearhead a new master’s program and the Center for Human Rights and the Arts at Bard College, in collaboration with longtime faculty members Thomas Keenan and Gideon Lester. Since mid-March, the team has premiered their first digital commission, launched a series of virtual talks, and begun actively recruiting its first cohort of international graduate students.

More here.

Among the Rank and File: Nikolai Gogol in the twilight of empire

Jennifer Wilson in The Nation:

Jennifer Wilson in The Nation:

The thing about big plans is that they require people to carry them out. The problem of personnel particularly plagued Peter the Great. Convinced by his European advisers that his country was backward and stuck in a medieval mindset, he spent much of his reign on a series of modernizing initiatives intended to get Russia “caught up” with the West. To implement his reforms—which included establishing a navy, imposing a tax on beards, and eventually drafting half a million serfs to build a city (named after himself) on nothing but marshland—he needed a robust bureaucracy and a standing military that could manage the demands of his new, spruced-up empire. Peter thus made service—civil or military—compulsory for the Russian nobility, and he implemented a new class system, the Table of Ranks, under which one could be promoted according to how long and how well one served.

The Table of Ranks included 14 classes, from collegiate registrars (which included lowly copy clerks) at the very bottom to the top civil rank of chancellor. While it was pitched as the introduction of a modern meritocratic system in Russia, in practice the table produced sharp class divisions, prevented people from working in fields that did not correspond to their rank, and tied social status to the name and nature of one’s profession. A version of this system continued in Russia all the way up to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and yet, in much of the literature of the 19th century, the civil service—which structured almost every aspect of life, particularly in the capital of St. Petersburg—feels weirdly merged into the background, more a fact of life than a facet of literary fiction, save for in the work of one writer: Nikolai Gogol.

More here.

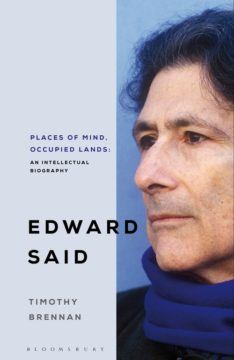

Palestinianism

Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB:

When Edward Said joined the Columbia University English department in 1963, a rumour spread that he was a Jew from Alexandria. He might as well have been. Born in Jerusalem in 1935 to well-off Palestinian Christian parents, he had grown up in the twilight years of multicultural Cairo, where many of his classmates were Egyptian Jews. His piano teacher was Ignace Tiegerman, a Polish Jew who had moved to Cairo in 1931 and founded a French-speaking conservatoire. Said’s closest friends at Princeton and Harvard, Arthur Gold, a brilliant Luftmensch prone to tormented idleness, and the future art critic Michael Fried, were Jews. His dissertation and first book were about Joseph Conrad’s explorations of ambiguity and double identities. As Timothy Brennan writes in Places of Mind, Said was ‘a photo negative of his Jewish counterparts’.

Said spent his first years at Columbia as a kind of an Arab Marrano, or crypto Palestinian, among Jewish and Wasp colleagues who were either indifferent or hostile to the Arab struggle with Israel. He published essays in the little magazines of the New York intellectuals, went to cocktail parties with Lionel Trilling and Mary McCarthy, and kept quiet about his identity and his politics. His parents, who were themselves estranged from Palestine (his father said Jerusalem reminded him of death), were relieved that their moody and contentious son was showing such prudence. Thanks to his father’s service in the American Expeditionary Forces during the First World War, Said was an American citizen, and if he was reinventing himself, well, that’s what immigrants did in the New World. The Egyptian literary theorist Ihab Hassan had shed his Arab identity when he moved to the US, and had never looked back.

But something in Said rebelled against the concealment and silence that the loss of Palestine had imposed, and that his father, William Said, had accepted, leaving behind not only the family’s past in Jerusalem but also his Arab name, Wadie.

More here.

Finding the Raga by Amit Chaudhuri

Oliver Craske at The Guardian:

For decades now, the novelist Amit Chaudhuri has begun each morning by singing the Indian classical raga “Todi”. It boasts a scale utterly alien to western music’s majors, minors and modes, and its emotional effect varies: for many people this raga, or melody form, evokes a sad beauty, while for others it is playful or unsettling. Chaudhuri spends an hour working through the same sequence of slow, medium and fast compositions every day, yet he never tires of them. Each time Todi unfolds differently, for this is a musical form of fractal-like complexity, that allows for endless explorations and improvisations within each raga’s framework.

For decades now, the novelist Amit Chaudhuri has begun each morning by singing the Indian classical raga “Todi”. It boasts a scale utterly alien to western music’s majors, minors and modes, and its emotional effect varies: for many people this raga, or melody form, evokes a sad beauty, while for others it is playful or unsettling. Chaudhuri spends an hour working through the same sequence of slow, medium and fast compositions every day, yet he never tires of them. Each time Todi unfolds differently, for this is a musical form of fractal-like complexity, that allows for endless explorations and improvisations within each raga’s framework.

If that sounds like a daunting way to start the day, bear in mind that this is a genre as incomprehensible to most Indians as it is to most Europeans. In childhood, if Chaudhuri heard someone singing it he would respond with parody or dismissal.

more here.

TM Krishna: Raga Thodi