John Farrell in Commonweal:

In the view of many scientists, Artificial Intelligence (AI) isn’t living up to the hype of its proponents. We don’t yet have safe driverless cars—and we’re not likely to in the near future. Nor are robots about to take on all our domestic drudgery so that we can devote more time to leisure. On the brighter side, robots are also not about to take over the world and turn humans into slaves the way they do in the movies.

In the view of many scientists, Artificial Intelligence (AI) isn’t living up to the hype of its proponents. We don’t yet have safe driverless cars—and we’re not likely to in the near future. Nor are robots about to take on all our domestic drudgery so that we can devote more time to leisure. On the brighter side, robots are also not about to take over the world and turn humans into slaves the way they do in the movies.

Nevertheless, there is real cause for concern about the impact AI is already having on us. As Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis write in their book, Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust, “the AI we have now simply can’t be trusted.” In their view, the more authority we prematurely turn over to current machine systems, the more worried we should be. “Some glitches are mild, like an Alexa that randomly giggles (or wakes you in the middle of the night, as happened to one of us), or an iPhone that autocorrects what was meant as ‘Happy Birthday, dear Theodore’ into ‘Happy Birthday, dead Theodore,’” they write. “But others—like algorithms that promote fake news or bias against job applicants—can be serious problems.”

Marcus and Davis cite a report by the AI Now Institute detailing AI problems in many different domains, including Medicaid-eligibility determination, jail-term sentencing, and teacher evaluations:

Flash crashes on Wall Street have caused temporary stock market drops, and there have been frightening privacy invasions (like the time an Alexa recorded a conversation and inadvertently sent it to a random person on the owner’s contact list); and multiple automobile crashes, some fatal. We wouldn’t be surprised to see a major AI-driven malfunction in an electrical grid. If this occurs in the heat of summer or the dead of winter, a large number of people could die.

The computer scientist Jaron Lanier has cited the darker aspects of AI as it has been exploited by social-media giants like Facebook and Google, where he used to work. In Lanier’s view, AI-driven social-media platforms promote factionalism and division among users, as starkly demonstrated in the 2016 and 2020 elections, when Russian hackers created fake social-media accounts to drive American voters toward Donald Trump. As Lanier writes in his book, Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, AI-driven social media are designed to commandeer the user’s attention and invade her privacy, to overwhelm her with content that has not been fact-checked or vetted. In fact, Lanier concludes, it is designed to “turn people into assholes.”

More here.

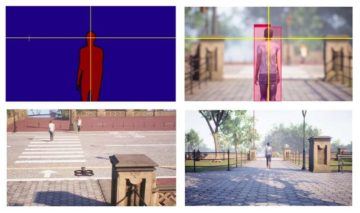

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, mobile robots and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) could enhance practices in a variety of fields, including cinematography. In recent years, many cinematographers and entertainment companies specifically began exploring the use of UAVs to capture high-quality aerial video footage (i.e., videos of specific locations taken from above). Researchers at University of Zaragoza and Stanford University recently created CineMPC, a computational tool that can be used for autonomously controlling a drone’s on-board video cameras. This technique, introduced in a paper pre-published on arXiv, could significantly enhance current cinematography practices based on the use of UAVs.

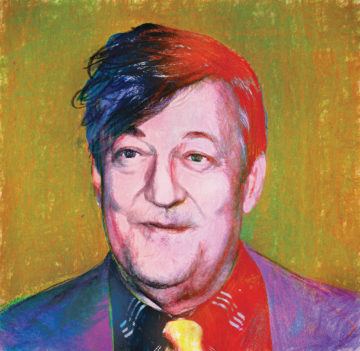

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, mobile robots and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) could enhance practices in a variety of fields, including cinematography. In recent years, many cinematographers and entertainment companies specifically began exploring the use of UAVs to capture high-quality aerial video footage (i.e., videos of specific locations taken from above). Researchers at University of Zaragoza and Stanford University recently created CineMPC, a computational tool that can be used for autonomously controlling a drone’s on-board video cameras. This technique, introduced in a paper pre-published on arXiv, could significantly enhance current cinematography practices based on the use of UAVs. Stephen Fry: I do. I loved him. He was adorable company, but I was also quite scared of him. He was a much tougher figure than I. He didn’t mind being disliked. He didn’t mind being howled down even. He seemed to enjoy it. I can quite imagine Hitchens being on the same platform with a Ben Shapiro perhaps. But I can’t imagine him having come out on the side of Trump. Hitchens just had a style that suited America despite his Britishness. It was the swagger. I miss that the culture doesn’t have enough of these sorts of people. Toward the last year of his life, I would visit another one of them, Gore Vidal, in Los Angeles, where he had his house; it was so overgrown in the garden that it was dark inside. He would retell stories of his great rows with Norman Mailer and Susan Sontag and William Buckley. Their arguments could be mordant and full of venom, but they weren’t as unhappy as so many debates now. There was a kind of joy and pleasure in the fight.

Stephen Fry: I do. I loved him. He was adorable company, but I was also quite scared of him. He was a much tougher figure than I. He didn’t mind being disliked. He didn’t mind being howled down even. He seemed to enjoy it. I can quite imagine Hitchens being on the same platform with a Ben Shapiro perhaps. But I can’t imagine him having come out on the side of Trump. Hitchens just had a style that suited America despite his Britishness. It was the swagger. I miss that the culture doesn’t have enough of these sorts of people. Toward the last year of his life, I would visit another one of them, Gore Vidal, in Los Angeles, where he had his house; it was so overgrown in the garden that it was dark inside. He would retell stories of his great rows with Norman Mailer and Susan Sontag and William Buckley. Their arguments could be mordant and full of venom, but they weren’t as unhappy as so many debates now. There was a kind of joy and pleasure in the fight. Recent White House initiatives suggest that addressing climate change has risen to the policy forefront of government at the presidential level for the first time in US history. Last week President Biden convened an online international meeting of heads of state on the issue and committed the US to a dramatic effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level of 50 percent of emissions in 2005 by the year 2030, which will require unprecedented action and cooperation between government and major industries.

Recent White House initiatives suggest that addressing climate change has risen to the policy forefront of government at the presidential level for the first time in US history. Last week President Biden convened an online international meeting of heads of state on the issue and committed the US to a dramatic effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level of 50 percent of emissions in 2005 by the year 2030, which will require unprecedented action and cooperation between government and major industries. In a new, well-documented

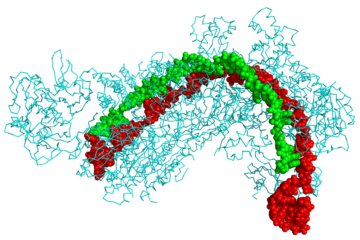

In a new, well-documented  The Nobel prize in chemistry awarded last year to the biochemists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for the genetic modification technique called CRISPR cemented the popular idea that a new era of precision manipulation of hereditary material had arrived. The award came on the heels of the unauthorized use of the technique by the scientist He Jiankui in 2018 in China in an effort to produce individuals (twin girls in this case) resistant to HIV, and a flurry of studies in early 2020 showing that accuracy in altering DNA in a test tube or bacteria in a culture dish, did not hold up when applied to animal embryos. Attempts to modify single genes in human embryos (not intended to be brought to full-term) in fact led to “

The Nobel prize in chemistry awarded last year to the biochemists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for the genetic modification technique called CRISPR cemented the popular idea that a new era of precision manipulation of hereditary material had arrived. The award came on the heels of the unauthorized use of the technique by the scientist He Jiankui in 2018 in China in an effort to produce individuals (twin girls in this case) resistant to HIV, and a flurry of studies in early 2020 showing that accuracy in altering DNA in a test tube or bacteria in a culture dish, did not hold up when applied to animal embryos. Attempts to modify single genes in human embryos (not intended to be brought to full-term) in fact led to “ After a decade of fighting for regulatory approval and public acceptance, a biotechnology firm has released genetically engineered mosquitoes into the open air in the United States for the first time. The experiment, launched this week in the Florida Keys — over the objections of some local critics — tests a method for suppressing populations of wild Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which can carry diseases such as Zika, dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever.

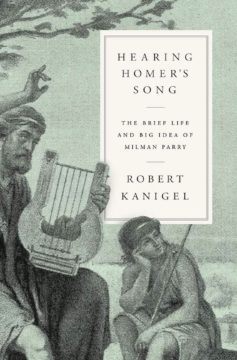

After a decade of fighting for regulatory approval and public acceptance, a biotechnology firm has released genetically engineered mosquitoes into the open air in the United States for the first time. The experiment, launched this week in the Florida Keys — over the objections of some local critics — tests a method for suppressing populations of wild Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which can carry diseases such as Zika, dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever. “The effects of oral states of consciousness,” Walter Ong wrote in his 1982 book Orality and Literacy, “are bizarre to the literate mind.” Parry theorized that, if he could find a find a culture where bards still practiced an oral tradition, singing songs as long as Homer’s (over 12,000 lines), he could prove the links between Homeric verse and Bosnian song that scholars had long been puzzling over. In his approach, Parry worked a different field with some of the same purpose Alan Lomax did in the American South during this same period, collecting a rural folk tradition in order to catalog the vast body of American song. The Muslim Slavs of Bosnia, where Parry focused his recording, were called “guslars,” and played a single-string instrument called the “gusle.”

“The effects of oral states of consciousness,” Walter Ong wrote in his 1982 book Orality and Literacy, “are bizarre to the literate mind.” Parry theorized that, if he could find a find a culture where bards still practiced an oral tradition, singing songs as long as Homer’s (over 12,000 lines), he could prove the links between Homeric verse and Bosnian song that scholars had long been puzzling over. In his approach, Parry worked a different field with some of the same purpose Alan Lomax did in the American South during this same period, collecting a rural folk tradition in order to catalog the vast body of American song. The Muslim Slavs of Bosnia, where Parry focused his recording, were called “guslars,” and played a single-string instrument called the “gusle.” Beyond all this violent contrarianism, the Lawrence Wilson wishes to paint is a figure of ‘mysteries rather than certainties’. The ‘burning man’ of her title derives from a letter of 1913 in which Lawrence the would-be martyr for his art compares himself to his namesake saint, who famously embraced his martyrdom (death on a gridiron) to the point of proclaiming, ‘Turn me over brothers, I am done enough on this side.’ Wilson’s target is less a straightforward biography than a sifting of Lawrence’s legacy for what remains urgent and alive, the aim being to shed its infernal baggage in search of an abiding paradise. One threat to her Dante comparison is how remote from heaven Lawrence increasingly appears, his attachment to the physical world growing shriller the weaker his grip on it becomes. But these tensions are all part of the drama, not least where the question of sex is concerned. Sex in Lawrence must always be a full-on sacramental affair, but in everyday life he was uptight and prissy about being touched, unlike the more easy-going Frieda.

Beyond all this violent contrarianism, the Lawrence Wilson wishes to paint is a figure of ‘mysteries rather than certainties’. The ‘burning man’ of her title derives from a letter of 1913 in which Lawrence the would-be martyr for his art compares himself to his namesake saint, who famously embraced his martyrdom (death on a gridiron) to the point of proclaiming, ‘Turn me over brothers, I am done enough on this side.’ Wilson’s target is less a straightforward biography than a sifting of Lawrence’s legacy for what remains urgent and alive, the aim being to shed its infernal baggage in search of an abiding paradise. One threat to her Dante comparison is how remote from heaven Lawrence increasingly appears, his attachment to the physical world growing shriller the weaker his grip on it becomes. But these tensions are all part of the drama, not least where the question of sex is concerned. Sex in Lawrence must always be a full-on sacramental affair, but in everyday life he was uptight and prissy about being touched, unlike the more easy-going Frieda. Not so long ago, there seemed to be something radical in rejecting the future. Looking back, it’s easy to see why. In the 1990s, history was over; the United States and capitalism had won. Strutting conservative televangelists and smug liberal technocrats took turns running the world. Globalization promised more of everything: more productivity, more innovation, more wealth. Economic prosperity and regressive moralism went hand in hand. The nuclear family was once again sacred, and non-normative sexuality remained stigmatized: Don’t ask, but also don’t tell. Conservatives—as well as some liberals—supported any policy that promised to protect children, born and unborn, so they might take advantage of the bright future that awaited them. Meritocracy was supposedly thriving, even as inequality prevailed everywhere.

Not so long ago, there seemed to be something radical in rejecting the future. Looking back, it’s easy to see why. In the 1990s, history was over; the United States and capitalism had won. Strutting conservative televangelists and smug liberal technocrats took turns running the world. Globalization promised more of everything: more productivity, more innovation, more wealth. Economic prosperity and regressive moralism went hand in hand. The nuclear family was once again sacred, and non-normative sexuality remained stigmatized: Don’t ask, but also don’t tell. Conservatives—as well as some liberals—supported any policy that promised to protect children, born and unborn, so they might take advantage of the bright future that awaited them. Meritocracy was supposedly thriving, even as inequality prevailed everywhere. The world has gone through a tough time with the COVID-19 pandemic. Every catastrophic event is unique, but there are certain commonalities to how such crises play out in our modern interconnected world. Historian Niall Ferguson wrote a book from a couple of years ago,

The world has gone through a tough time with the COVID-19 pandemic. Every catastrophic event is unique, but there are certain commonalities to how such crises play out in our modern interconnected world. Historian Niall Ferguson wrote a book from a couple of years ago,  The governments of South Africa, India, and dozens of other developing countries are calling for the rights on intellectual property (IP), including vaccine patents, to be waived to accelerate the worldwide production of supplies to fight COVID-19. They are absolutely correct. IP for fighting COVID-19 should be waived, and indeed actively shared among scientists, companies, and nations.

The governments of South Africa, India, and dozens of other developing countries are calling for the rights on intellectual property (IP), including vaccine patents, to be waived to accelerate the worldwide production of supplies to fight COVID-19. They are absolutely correct. IP for fighting COVID-19 should be waived, and indeed actively shared among scientists, companies, and nations. Each year, researchers from around the world gather at Neural Information Processing Systems, an artificial-intelligence conference, to discuss automated translation software, self-driving cars, and abstract mathematical questions. It was odd, therefore, when Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, gave a presentation at the 2018 conference, which was held in Montreal. Fifty-one, with light-green eyes and a dark beard that lend him a mischievous air, Levin studies how bodies grow, heal, and, in some cases, regenerate. He waited onstage while one of Facebook’s A.I. researchers introduced him, to a packed exhibition hall, as a specialist in “computation in the medium of living systems.”

Each year, researchers from around the world gather at Neural Information Processing Systems, an artificial-intelligence conference, to discuss automated translation software, self-driving cars, and abstract mathematical questions. It was odd, therefore, when Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, gave a presentation at the 2018 conference, which was held in Montreal. Fifty-one, with light-green eyes and a dark beard that lend him a mischievous air, Levin studies how bodies grow, heal, and, in some cases, regenerate. He waited onstage while one of Facebook’s A.I. researchers introduced him, to a packed exhibition hall, as a specialist in “computation in the medium of living systems.” I remember the first time I ever saw a ghost. I was tiptoeing through the remnants of a burnt-out row house in Washington, D.C., in one of the neighborhoods where, in the 1990s, one could still discern the architectural scars from the urban rebellions meant to avenge the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., thirty years before.

I remember the first time I ever saw a ghost. I was tiptoeing through the remnants of a burnt-out row house in Washington, D.C., in one of the neighborhoods where, in the 1990s, one could still discern the architectural scars from the urban rebellions meant to avenge the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., thirty years before.