Elizabeth Stokoe in Nature:

Conversation has been described1 as “the primordial site of human sociality”. We all have a lifetime’s experience to draw on if asked how it works, or when we reflect on the conversations we have participated in. But because conversation is something that we know tacitly how to do, scientific attempts to understand it are often relegated to the ‘soggy’ end of social psychology. Conversation certainly differs from other subjects of scientific scrutiny. For instance, black holes do not exist to be understood by people, whereas conversation exists only to be understood by people and to help us understand each other. Writing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Mastroianni et al.2 report how they have taken up the challenge of researching conversation scientifically.

Conversation has been described1 as “the primordial site of human sociality”. We all have a lifetime’s experience to draw on if asked how it works, or when we reflect on the conversations we have participated in. But because conversation is something that we know tacitly how to do, scientific attempts to understand it are often relegated to the ‘soggy’ end of social psychology. Conversation certainly differs from other subjects of scientific scrutiny. For instance, black holes do not exist to be understood by people, whereas conversation exists only to be understood by people and to help us understand each other. Writing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Mastroianni et al.2 report how they have taken up the challenge of researching conversation scientifically.

The authors focused on the question of whether conversations end when people want them to, and gathered data from two studies. In the first one, individuals (806 in total) taking part in an online survey were asked to recall the most recent conversation they had in person, report its duration and indicate whether it ended when they wanted it to. If they indicated that the conversation didn’t end when they wanted, they were asked to estimate how much longer or shorter they would have liked it to have been. Participants were also asked how they thought the person they were speaking to might have answered the same questions. These conversations were mostly between people who were familiar to each other; 88% were between those who had known each other for at least a year, and 84% of the participants spoke to the person in question at least a few times each week.

More here.

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he  As he later told the story in Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft, he was brushed off by many in the scientific establishment — and so went to extraordinary lengths to prove the theory’s plausibility, reconstructing the ancient journey by sailing across the sea on a wooden raft in 1947. This spectacular feat captured the imagination of the world, and researchers, skeptical as they might have been, have ever since debated what really had happened in prehistoric times between South America and Polynesia (the group of Pacific islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii). Most scientists never accepted the amateur anthropology in which Heyerdahl couched his theory, but the mystery of an ancient trans-Pacific journey was a live one. All sorts of evidence would be marshalled, sometimes seeming to affirm Heyerdahl in part, sometimes seeming to show him entirely wrong.

As he later told the story in Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft, he was brushed off by many in the scientific establishment — and so went to extraordinary lengths to prove the theory’s plausibility, reconstructing the ancient journey by sailing across the sea on a wooden raft in 1947. This spectacular feat captured the imagination of the world, and researchers, skeptical as they might have been, have ever since debated what really had happened in prehistoric times between South America and Polynesia (the group of Pacific islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii). Most scientists never accepted the amateur anthropology in which Heyerdahl couched his theory, but the mystery of an ancient trans-Pacific journey was a live one. All sorts of evidence would be marshalled, sometimes seeming to affirm Heyerdahl in part, sometimes seeming to show him entirely wrong. Milman Parry was arguably the most important American classical scholar of the 20th century, by one reckoning “the Darwin of Homeric Studies.” At age 26, this young man from California stepped into the world of Continental philologists and overturned some of their most deeply cherished notions of ancient literature. Homer, Parry showed, was no “writer” at all. The

Milman Parry was arguably the most important American classical scholar of the 20th century, by one reckoning “the Darwin of Homeric Studies.” At age 26, this young man from California stepped into the world of Continental philologists and overturned some of their most deeply cherished notions of ancient literature. Homer, Parry showed, was no “writer” at all. The  At the core of Anton Chekov’s short story, ‘

At the core of Anton Chekov’s short story, ‘ Released from the silo of conventional philosophy, I found the neuroscientists at the medical school to be uniformly hospitable and curious about what I was up to. A human brain was indeed delivered to me in the anatomy lab, and holding it my hands, I felt an almost reverential humility toward this tissue that had embodied someone’s love and knowledge and skills. It looked so small, relative to what a human brain can do.

Released from the silo of conventional philosophy, I found the neuroscientists at the medical school to be uniformly hospitable and curious about what I was up to. A human brain was indeed delivered to me in the anatomy lab, and holding it my hands, I felt an almost reverential humility toward this tissue that had embodied someone’s love and knowledge and skills. It looked so small, relative to what a human brain can do. In cities big and small, hospitals are too full to accept new patients and diagnostic centers take up to three days or more to do chest scans of those who might have Covid-19. Doctors and hospital staff are completely exhausted.

In cities big and small, hospitals are too full to accept new patients and diagnostic centers take up to three days or more to do chest scans of those who might have Covid-19. Doctors and hospital staff are completely exhausted.

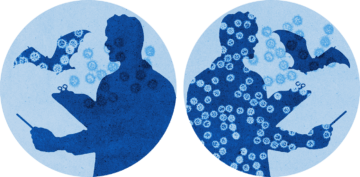

“In North America we pose a far greater risk to our bats than they do to us,” said O’Keefe, a bat ecologist and professor of environmental science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease, an illness that jumped from animal hosts to humans. But disease transfer isn’t just a one-way street. It takes only a bit of evolutionary bad luck to turn a bat’s head cold into a human’s killer. But it takes only a little more for the same virus to jump from humans to other animals. Zoonosis begets reverse zoonosis, which can, in turn, come back around to zoonosis again. A virus we give to a bat could, someday, come back around to reinfect us. Animals’ health is ours, ours is theirs, theirs is ours.

“In North America we pose a far greater risk to our bats than they do to us,” said O’Keefe, a bat ecologist and professor of environmental science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease, an illness that jumped from animal hosts to humans. But disease transfer isn’t just a one-way street. It takes only a bit of evolutionary bad luck to turn a bat’s head cold into a human’s killer. But it takes only a little more for the same virus to jump from humans to other animals. Zoonosis begets reverse zoonosis, which can, in turn, come back around to zoonosis again. A virus we give to a bat could, someday, come back around to reinfect us. Animals’ health is ours, ours is theirs, theirs is ours. Polidori: Well, America is a Protestant country. Protestants don’t take so well to pathos, so they think that I’m a reactionary, because I am making misery look beautiful. And so because of this, I am minimizing the plight of the victims. I only get this in Anglo-Saxon countries, the rest of the world doesn’t think that way.

Polidori: Well, America is a Protestant country. Protestants don’t take so well to pathos, so they think that I’m a reactionary, because I am making misery look beautiful. And so because of this, I am minimizing the plight of the victims. I only get this in Anglo-Saxon countries, the rest of the world doesn’t think that way. On the stage of an empty concert hall, the Austrian-born composer

On the stage of an empty concert hall, the Austrian-born composer  I often think about George Berkeley’s observation (without recalling quite where he offered it) that when we think we are imagining to ourselves the heat of the sun, what we are really imagining is the heat of a stove or a similar familiar source of mundane household warmth. A stove is already hot enough to reduce my hand to ash fairly quickly. And without a hand left, without any nerve endings to give me any report at all on the external world, I’m hardly in a position to note the difference between 300 degrees Fahrenheit and 5,700 degrees Kelvin. Both, Berkeley thinks, are just too darn hot.

I often think about George Berkeley’s observation (without recalling quite where he offered it) that when we think we are imagining to ourselves the heat of the sun, what we are really imagining is the heat of a stove or a similar familiar source of mundane household warmth. A stove is already hot enough to reduce my hand to ash fairly quickly. And without a hand left, without any nerve endings to give me any report at all on the external world, I’m hardly in a position to note the difference between 300 degrees Fahrenheit and 5,700 degrees Kelvin. Both, Berkeley thinks, are just too darn hot. The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities.

The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities. Last week, the American Humanist Association (AHA) stripped British author Richard Dawkins of his 1996 Humanist of the Year award after he made a comment on Twitter that offended some in the transgender community.

Last week, the American Humanist Association (AHA) stripped British author Richard Dawkins of his 1996 Humanist of the Year award after he made a comment on Twitter that offended some in the transgender community.