https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ST_NXyEVmrI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ST_NXyEVmrI

Witold Rybczynski at The Hedgehog Review:

“Good architecture can be startling, or at least might not look like what we are used to,” writes the critic Aaron Betsky in Architect magazine. “Experimentation can sometimes look weird at first, but it is a necessary part of figuring out how to make our human-built world better.” Now so used to buildings that break the bounds of convention, we find the suggestion that experimentation is an essential part of good architecture unremarkable, even banal. But is it true?

“Good architecture can be startling, or at least might not look like what we are used to,” writes the critic Aaron Betsky in Architect magazine. “Experimentation can sometimes look weird at first, but it is a necessary part of figuring out how to make our human-built world better.” Now so used to buildings that break the bounds of convention, we find the suggestion that experimentation is an essential part of good architecture unremarkable, even banal. But is it true?

Berlin’s Altes Museum, built in 1822, doesn’t look like a plumbing fixture. Its architect, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, modeled the 300-foot façade of giant Ionic columns on an ancient Greek stoa (a covered walkway or portico). Inside, he based a two-story-high rotunda on the Roman Pantheon. Schinkel was one of the most inventive architects of the nineteenth century—the plan of the museum, with its circuit of long, narrow galleries, was without precedent, and the severe side and rear elevations, which would inspire later modernists such as Mies van der Rohe, were almost shockingly plain. Yet like so many architects before him, Schinkel kept one eye on the past. That meant imitation as well as invention.

more here.

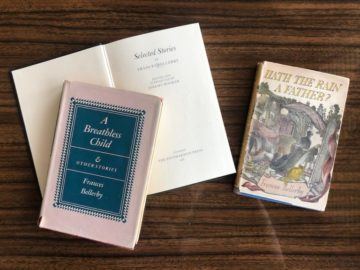

Lucy Scholes at The Paris Review:

In Women’s Fiction and the Great War (1997), Nathalie Blondel argues that Bellerby spent the rest of her life replaying this grief in her fiction. “People live double lives” in Bellerby’s stories, Blondel explains: they exist in the land of the living while also “dwelling in memories of the dead.” Like Sabine Coelsch-Foisner—who, in her chapter on women’s writing in the first half of the twentieth-century in The British and Irish Short Story (2008), argues that “Bellerby’s stories typically convey a halt in the continuum of life and verge on the unspeakable”—Blondel highlights how Bellerby demonstrates this linguistically: “the estrangement of the bereaved from the world of the living is imaged through their estrangement from language itself.”

In Women’s Fiction and the Great War (1997), Nathalie Blondel argues that Bellerby spent the rest of her life replaying this grief in her fiction. “People live double lives” in Bellerby’s stories, Blondel explains: they exist in the land of the living while also “dwelling in memories of the dead.” Like Sabine Coelsch-Foisner—who, in her chapter on women’s writing in the first half of the twentieth-century in The British and Irish Short Story (2008), argues that “Bellerby’s stories typically convey a halt in the continuum of life and verge on the unspeakable”—Blondel highlights how Bellerby demonstrates this linguistically: “the estrangement of the bereaved from the world of the living is imaged through their estrangement from language itself.”

The impact of her brother’s death manifests most explicitly in these stories that make direct reference to the war, but grief filters into many of the other pieces, too: “Come to an End,” in which a father struggles to tell his son that the boy’s little sister has been killed in an accident, or “Such an Experienced House,” another unexpected ghost story, in which a musically gifted child creeps downstairs one night to find out who’s playing the piano so beautifully, only to be confronted with an apparition of herself at the keys.

more here.

Gabrielle Carey in the Sydney Review of Books:

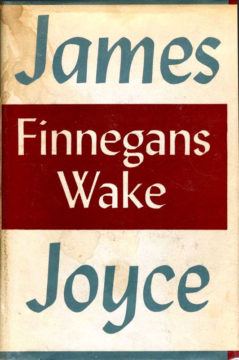

James Joyce once famously said that if it took him seventeen years to write Finnegans Wake, then a reader should take seventeen years to read it. In his usual prophetic way, he turned out to be exactly right. My Finnegans Wake Reading Group started in July 2004. We finished in February 2021.

James Joyce once famously said that if it took him seventeen years to write Finnegans Wake, then a reader should take seventeen years to read it. In his usual prophetic way, he turned out to be exactly right. My Finnegans Wake Reading Group started in July 2004. We finished in February 2021.

‘We’ll be dead before we get to the end!’ we often joked. In a sense we never really expected to arrive at the famous last words: A way a lone a last a loved a long the

And then it happened: page 628 was within reach.

James Joyce received the first copy of Finnegans Wake in his hands on 30 January, 1939, just in time for his 57th birthday on 2 February. So I scheduled our final reading for 2 February, 2021. But then I postponed it. And postponed it again. And then a third time. I had never done that before. For seventeen years I had been religious about sticking to the set day and time – the last Sunday of every month – no matter what. But now I realised there was part of me that didn’t want to read that final page. Because what would I do next? Finishing Finnegans Wake felt like the end of a long, literary marriage and I instinctively understood what that meant: a bad case of post break-up blues. Or was it because I’d been convinced that the Wake was a world without end when in fact, as Joyce writes, it was whorled without aimed.

More here.

Kelsey Houston-Edwards in Quanta:

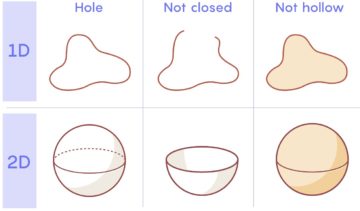

At first, topology can seem like an unusually imprecise branch of mathematics. It’s the study of squishy play-dough shapes capable of bending, stretching and compressing without limit. But topologists do have some restrictions: They cannot create or destroy holes within shapes. (It’s an old joke that topologists can’t tell the difference between a coffee mug and a doughnut, since they both have one hole.) While this might seem like a far cry from the rigors of algebra, a powerful idea called homology helps mathematicians connect these two worlds.

At first, topology can seem like an unusually imprecise branch of mathematics. It’s the study of squishy play-dough shapes capable of bending, stretching and compressing without limit. But topologists do have some restrictions: They cannot create or destroy holes within shapes. (It’s an old joke that topologists can’t tell the difference between a coffee mug and a doughnut, since they both have one hole.) While this might seem like a far cry from the rigors of algebra, a powerful idea called homology helps mathematicians connect these two worlds.

The word “hole” has many meanings in everyday speech — bubbles, rubber bands and bowls all have different kinds of holes. Mathematicians are interested in detecting a specific type of hole, which can be described as a closed and hollow space. A one-dimensional hole looks like a rubber band. The squiggly line that forms a rubber band is closed (unlike a loose piece of string) and hollow (unlike the perimeter of a penny).

Extending this logic, a two-dimensional hole looks like a hollow ball. The kinds of holes mathematicians are looking for — closed and hollow — are found in basketballs, but not bowls or bowling balls.

But mathematics traffics in rigor, and while thinking about holes this way may help point our intuition toward rubber bands and basketballs, it isn’t precise enough to qualify as a mathematical definition.

More here.

Tomas Pueyo in Uncharted Territories:

What if I told you that History is not random? That it follows clear rules?

What if I told you that History is not random? That it follows clear rules?

What if whoever conquered the US landmass was condemned to become an empire? What if China was always meant to be another empire? What if Europe had all the best geographic assets to make it the breakout continent? What if Northern Europe was always going to be richer than the South, no matter the protestant and catholic ethics? What if Africa’s geography holds it behind?

What if the land determined which tribes developed the technology to grow into cities? Which ones would become kingdoms and empires?

And what if I told you we’re leaving all this geographic influence behind?

Mankind is turning a page.

We’re starting a new chapter.

History is moving to the Cloud.

Because History is about to change. Everything that determines the success or failure of a country has turned upside down.

More here.

The wood of the madrone burns with a flame once

lavender and mossy green, a color you sometimes see in a sari.

Oak burns with a peppery smell.

For a really hot fire, use bark.

You can crack your stove with bark.

All winter long I make wood stews:

Poem to stove to woodpile to stove to

typewriter ……. woodpile ……. stove.

and can’t stop peeking at it!

can’t stop opening the door!

can’t stop giggling at it

crazy as Han Shan as

Wittgenstein in his German hut, as

all the others ever were and are

………………. Ancient Order of Fire Gigglers

who walked away from it, finally,

kicked the habit, finally, of Self, of

man-hooked Man

………………. ( which is not, at last, estrangement )

by Lew Welsh

from Ring of Bone

Grey Fox Press.1960

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GHMD05OcJTQ

Antonio Muñoz Molina at The Hudson Review:

I walk into the museum with a feeling of wonder as well as a slight sense of mistrust. I do not want to forget that it is a very recent invention. Thousands of years before the written book, or even before the birth of writing, the world was already filled with stories, with poems as elaborate as the Iliad, which in turn is almost new in comparison with Gilgamesh. The Prado, which was one of the first museums, is exactly two hundred years old, about the same age as the word “art” in the simultaneously sacral and restricted sense we bestow on it. The earliest known carved or painted images, on the other hand, were made over forty thousand years ago, and may have to be traced back still many more millennia if the dating of certain paintings attributed to Neanderthals is confirmed. If museums did not exist, if the term “art history” had never been coined, we would still have the wild horses of Chauvet, the heads and figures of the Cyclades, the whales, bears, and seals carved in ivory by the Inuit. We would still have Las Meninas, the wooden Christ of Medinaceli, the religious medals and cards that are worshipped and sold not far from here: Ladies of Sorrows; bloody effigies of Christ carried through town on the shoulders of a rapturously fervent Catholic crowd during Easter in the region where I was born; or the Holy Face, archaic and stern, that I used to see as a child in the cathedral of Jaén, a face that according to Church doctrine and common belief is not a painting made by the human hand but rather the true and miraculous impression of the face of Christ on the veil with which a woman named Veronica tried to wipe away his sweat and blood as he carried the Cross.

more here.

Johanna Fateman at Artforum:

Feminist is not a descriptor she embraced until late in life (she died in 2002 at the age of seventy-one). Mostly, it’s a label that has been bestowed upon her in attempts to contend with her quixotic ambition. Her resistance to the term, though, derived not from a real quarrel with its meaning so much as from some murky combination of misunderstanding, eccentricity, and calculation. Her personal brand of rebellion emerged before the advent of the women’s movement proper, in the pregnant pause between the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex in 1949 (when she was an eighteen-year-old fashion model about to marry her first husband, Harry Mathews) and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963, by which point Saint Phalle had already taken up arms against the church, the Father, and the picture plane. Her wrath against her family for her abusive, conformist upbringing, and her determination to revolt, in life and art, emerged independently of any movement or schooling. Hospitalized in 1953 after a suicide attempt—the low point of a psychic deterioration instigated by the realities of marriage and motherhood—she became an artist over the course of her six-week stay.

Feminist is not a descriptor she embraced until late in life (she died in 2002 at the age of seventy-one). Mostly, it’s a label that has been bestowed upon her in attempts to contend with her quixotic ambition. Her resistance to the term, though, derived not from a real quarrel with its meaning so much as from some murky combination of misunderstanding, eccentricity, and calculation. Her personal brand of rebellion emerged before the advent of the women’s movement proper, in the pregnant pause between the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex in 1949 (when she was an eighteen-year-old fashion model about to marry her first husband, Harry Mathews) and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963, by which point Saint Phalle had already taken up arms against the church, the Father, and the picture plane. Her wrath against her family for her abusive, conformist upbringing, and her determination to revolt, in life and art, emerged independently of any movement or schooling. Hospitalized in 1953 after a suicide attempt—the low point of a psychic deterioration instigated by the realities of marriage and motherhood—she became an artist over the course of her six-week stay.

more here.

Sana Goyal in The Guardian:

The opening chapter of How to Kidnap the Rich comes to a close with the narrator, a chai wallah’s son and con artist, clarifying that this isn’t a story about poverty, it’s a story about wealth. A few pages further in, we’re told that Delhi isn’t saffron; isn’t spice – it’s sweat. In Rahul Raina’s satirical state-of-the-nation debut, which slices into the soul of contemporary Indian society, things aren’t always the way they appear.

The opening chapter of How to Kidnap the Rich comes to a close with the narrator, a chai wallah’s son and con artist, clarifying that this isn’t a story about poverty, it’s a story about wealth. A few pages further in, we’re told that Delhi isn’t saffron; isn’t spice – it’s sweat. In Rahul Raina’s satirical state-of-the-nation debut, which slices into the soul of contemporary Indian society, things aren’t always the way they appear.

Ramesh Kumar is himself a sham. Having long left behind a childhood filled with abject poverty on the streets of East Delhi, a “grey smear on Google Maps”, he becomes an “examinations consultant” who commits academic fraud. Now a self-proclaimed “charming, witty, urbane man about town”, he sits entrance exams that are entry points to the west – the best universities, “the whitest lives” – for the elite. When Rudi, a teenager with a “no-matches-on-Tinder-face”, opts for the “All India Examinations: Premium Package”, little does Ramesh know that it will gain him beyond-belief riches and cost him a finger. If you place in the top thousand, it’s your ticket out of India. But what if you rank first?

More here.

Jonathan O’Callaghan in Nautilus:

The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities. Seen in this way, the inexorable rise in entropy, or disorder, as quantified by the second law of thermodynamics, takes on an almost mathematical certainty. So of course physicists are constantly trying to break it.

The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities. Seen in this way, the inexorable rise in entropy, or disorder, as quantified by the second law of thermodynamics, takes on an almost mathematical certainty. So of course physicists are constantly trying to break it.

One almost did. A thought experiment devised by the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1867 stumped scientists for 115 years. And even after a solution was found, physicists have continued to use “Maxwell’s demon” to push the laws of the universe to their limits. In the thought experiment, Maxwell imagined splitting a room full of gas into two compartments by erecting a wall with a small door. Like all gases, this one is made of individual particles. The average speed of the particles corresponds to the temperature of the gas—faster is hotter. But at any given time, some particles will be moving more slowly than others.

What if, suggested Maxwell, a tiny imaginary creature—a demon, as it was later called—sat at the door. Every time it saw a fast-moving particle approaching from the left-hand side, it opened the door and let it into the right-hand compartment. And every time a slow-moving particle approached from the right, the demon let it into the left-hand compartment.

More here.

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

On arriving in Paris in 2013, I went to open a bank account. The personal banker assigned to me, who would remain with me for a few years after that, was a Senegalese immigrant, a proud professional, and most of all a proud Frenchwoman. When I showed her my immigration papers and my confirmation of employment by the University of Paris, she said something like, “Oh, sure, you’re one of the good immigrants.” I thought she had meant to speak damningly of the hypocrisy of her adoptive country, and I started to say, “You mean because I’m…”. But before I got to that color-coding adjective I wrongly presumed she had in mind, she completed her thought: “You’re one of the good immigrants, like me. You’ve got diplomas, you’ve got a job.” Then she pointed to the family of Roma people encamped on a styrofoam mattress on the sidewalk right outside: “Not like them,” she said, “they don’t want to work. It’s easier to just sit there and make people feel sorry for you.”

On arriving in Paris in 2013, I went to open a bank account. The personal banker assigned to me, who would remain with me for a few years after that, was a Senegalese immigrant, a proud professional, and most of all a proud Frenchwoman. When I showed her my immigration papers and my confirmation of employment by the University of Paris, she said something like, “Oh, sure, you’re one of the good immigrants.” I thought she had meant to speak damningly of the hypocrisy of her adoptive country, and I started to say, “You mean because I’m…”. But before I got to that color-coding adjective I wrongly presumed she had in mind, she completed her thought: “You’re one of the good immigrants, like me. You’ve got diplomas, you’ve got a job.” Then she pointed to the family of Roma people encamped on a styrofoam mattress on the sidewalk right outside: “Not like them,” she said, “they don’t want to work. It’s easier to just sit there and make people feel sorry for you.”

More here.

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

“A way that math can make the world a better place is by making it a more interesting place to be a conscious being.” So says mathematician Emily Riehl near the start of this episode, and it’s a good summary of what’s to come. Emily works in realms of topology and category theory that are far away from practical applications, or even to some non-practical areas of theoretical physics. But they help us think about what is possible and how everything fits together, and what’s more interesting than that? We talk about what topology is, the specific example of homotopy — how things deform into other things — and how thinking about that leads us into groups, rings, groupoids, and ultimately to category theory, the most abstract of them all.

“A way that math can make the world a better place is by making it a more interesting place to be a conscious being.” So says mathematician Emily Riehl near the start of this episode, and it’s a good summary of what’s to come. Emily works in realms of topology and category theory that are far away from practical applications, or even to some non-practical areas of theoretical physics. But they help us think about what is possible and how everything fits together, and what’s more interesting than that? We talk about what topology is, the specific example of homotopy — how things deform into other things — and how thinking about that leads us into groups, rings, groupoids, and ultimately to category theory, the most abstract of them all.

More here.

Teresa Carr in Undark:

One idle Saturday afternoon I wreaked havoc on the virtual town of Harmony Square, “a green and pleasant place,” according to its founders, famous for its pond swan, living statue, and Pineapple Pizza Festival. Using a fake news site called Megaphone — tagged with the slogan “everything louder than everything else” — and an army of bots, I ginned up outrage and divided the citizenry. In the end, Harmony Square was in shambles.

One idle Saturday afternoon I wreaked havoc on the virtual town of Harmony Square, “a green and pleasant place,” according to its founders, famous for its pond swan, living statue, and Pineapple Pizza Festival. Using a fake news site called Megaphone — tagged with the slogan “everything louder than everything else” — and an army of bots, I ginned up outrage and divided the citizenry. In the end, Harmony Square was in shambles.

I thoroughly enjoyed my 10 minutes of villainy — even laughed outright a few times. And that was the point. My beleaguered town is the center of the action for the online game Breaking Harmony Square, a collaboration between the U.S. Departments of State and Homeland Security, psychologists at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, and DROG, a Dutch initiative that uses gaming and education to fight misinformation. In my role as Chief Disinformation Officer of Harmony Square, I learned about the manipulation techniques people use to gain a following, foment discord, and then exploit societal tensions for political purposes.

More here.

Adrian Searle at The Guardian:

Akomfrah plays fast and loose with time and place, the real and the constructed, to make larger, more complex narratives. A second three-screen video, Triptych, set in an unnamed location, is a panoply of street portraits. The title is taken from a track by jazz drummer and composer Max Roach, from his 1960 album We Insist! Roach’s wonderful Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace, which provides the soundtrack, with singer Abbey Lincoln keening and wailing wordlessly as Akomfrah’s camera glides and pauses. Practitioners of Candomblé, transgender people and queers of all sorts, street musicians, sassy kids and game old ladies, families, friends and passersby pose and smile for Akomfrah’s camera. Towards the end, we see an overhead shot of a vast portrait commemorating Breonna Taylor (shot dead by US police in her home in March last year), covering two basketball courts in Annapolis, Maryland.

Akomfrah plays fast and loose with time and place, the real and the constructed, to make larger, more complex narratives. A second three-screen video, Triptych, set in an unnamed location, is a panoply of street portraits. The title is taken from a track by jazz drummer and composer Max Roach, from his 1960 album We Insist! Roach’s wonderful Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace, which provides the soundtrack, with singer Abbey Lincoln keening and wailing wordlessly as Akomfrah’s camera glides and pauses. Practitioners of Candomblé, transgender people and queers of all sorts, street musicians, sassy kids and game old ladies, families, friends and passersby pose and smile for Akomfrah’s camera. Towards the end, we see an overhead shot of a vast portrait commemorating Breonna Taylor (shot dead by US police in her home in March last year), covering two basketball courts in Annapolis, Maryland.

more here.

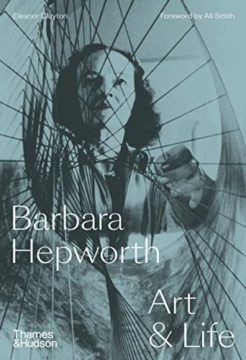

Tanya Harrod at Literary Review:

Barbara Hepworth’s life was by any standard a remarkable one. It was a triumph of determination. She did not come from a deprived background: her father was a civil engineer who became a well-respected county surveyor for the West Riding of Yorkshire. She went to a good school and was exceptionally gifted musically. She wrote with great clarity and was an accomplished draughtswoman. She sailed into Leeds School of Art and in 1921 won a senior scholarship to the Royal College of Art, then under the invigorating leadership of the recently appointed William Rothenstein. At the college, which at the time occupied a building attached to the Victoria and Albert Museum, she chose to concentrate on sculpture, drawing from casts, modelling in clay, carving reliefs in plaster, with some stone and wood carving too. It was a traditional education, undertaken alongside another student from Yorkshire, Henry Moore.

Barbara Hepworth’s life was by any standard a remarkable one. It was a triumph of determination. She did not come from a deprived background: her father was a civil engineer who became a well-respected county surveyor for the West Riding of Yorkshire. She went to a good school and was exceptionally gifted musically. She wrote with great clarity and was an accomplished draughtswoman. She sailed into Leeds School of Art and in 1921 won a senior scholarship to the Royal College of Art, then under the invigorating leadership of the recently appointed William Rothenstein. At the college, which at the time occupied a building attached to the Victoria and Albert Museum, she chose to concentrate on sculpture, drawing from casts, modelling in clay, carving reliefs in plaster, with some stone and wood carving too. It was a traditional education, undertaken alongside another student from Yorkshire, Henry Moore.

more here.