Aqsa Ijaz at Marginalia Review:

A whole way of seeing and representing the world has faded with the loss of such forms of storytelling. And its absence is felt by those who study the past through the cracks of those stories, which were neither histories nor fictions but a unique perspective on reality that used both these modes of comprehension. As Stewart, in his book on the premodern Bengali storytelling tradition, Witness to Marvels: Sufism and Literary Imagination (2019), suggests, narratives are never subject to the test of truthfulness precisely because they are literary. It is different from saying that they are false because they are fiction. They don’t operate on the principle of having a truth-claim but possess a truth-value, giving way to a different kind of contract between the listener and the storyteller. Such an engagement illuminates the function of these narratives rather than the mere verifiability of their content. As Khan tells us in his book, The Broken Spell: Indian Storytelling and the Romance Genre in Persian and Urdu (2019), the storytellers in premodern North India were crucial to the social fabric. By telling age-old stories with new twists and turns that were instructed and provided models of emulation for an ethical life and good conduct, they kept the past contemporaneous with the present.

A whole way of seeing and representing the world has faded with the loss of such forms of storytelling. And its absence is felt by those who study the past through the cracks of those stories, which were neither histories nor fictions but a unique perspective on reality that used both these modes of comprehension. As Stewart, in his book on the premodern Bengali storytelling tradition, Witness to Marvels: Sufism and Literary Imagination (2019), suggests, narratives are never subject to the test of truthfulness precisely because they are literary. It is different from saying that they are false because they are fiction. They don’t operate on the principle of having a truth-claim but possess a truth-value, giving way to a different kind of contract between the listener and the storyteller. Such an engagement illuminates the function of these narratives rather than the mere verifiability of their content. As Khan tells us in his book, The Broken Spell: Indian Storytelling and the Romance Genre in Persian and Urdu (2019), the storytellers in premodern North India were crucial to the social fabric. By telling age-old stories with new twists and turns that were instructed and provided models of emulation for an ethical life and good conduct, they kept the past contemporaneous with the present.

more here.

With the vanishing of the name goes the disappearance of the object, the slice of art, the fragment of literature, the portion of music. With the fading of the thing, so the name is gradually effaced from memory, and whatever there was becomes anonymous.

With the vanishing of the name goes the disappearance of the object, the slice of art, the fragment of literature, the portion of music. With the fading of the thing, so the name is gradually effaced from memory, and whatever there was becomes anonymous.

In his previous essay collection,

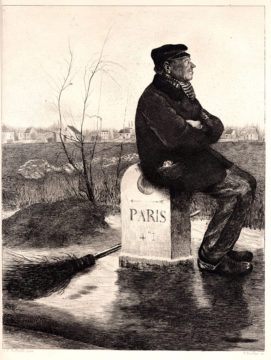

In his previous essay collection,  Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless.

Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless. Back in the 1880s, the mathematician and theologian Edwin Abbott tried to help us better understand our world by describing a very different one he called Flatland. Imagine a world that is not a sphere moving through space like our own planet, but more like a vast sheet of paper inhabited by conscious, flat geometric shapes. These shape-people can move forwards and backwards, and they can turn left and right. But they have no sense of up or down. The very idea of a tree, or a well, or a mountain makes no sense to them because they lack the concepts and experiences of height and depth. They cannot imagine, let alone describe, objects familiar to us.

Back in the 1880s, the mathematician and theologian Edwin Abbott tried to help us better understand our world by describing a very different one he called Flatland. Imagine a world that is not a sphere moving through space like our own planet, but more like a vast sheet of paper inhabited by conscious, flat geometric shapes. These shape-people can move forwards and backwards, and they can turn left and right. But they have no sense of up or down. The very idea of a tree, or a well, or a mountain makes no sense to them because they lack the concepts and experiences of height and depth. They cannot imagine, let alone describe, objects familiar to us. In bare skin, tingling in the 8C (46F) water, Craig Foster swims into the waters off the Western Cape of South Africa and immerses himself in the Atlantic Ocean. In many ways, he is a broken man. Depleted and disconnected, he slowly dives into the all-powerful and unfriendly waters, and finds shelter in the tranquil kelp forest below – an area which he has not connected with since his childhood. As he glides through the undisturbed kelp landscape, he is overwhelmed with his smallness in this almost alien landscape. He is alone, but not for long.

In bare skin, tingling in the 8C (46F) water, Craig Foster swims into the waters off the Western Cape of South Africa and immerses himself in the Atlantic Ocean. In many ways, he is a broken man. Depleted and disconnected, he slowly dives into the all-powerful and unfriendly waters, and finds shelter in the tranquil kelp forest below – an area which he has not connected with since his childhood. As he glides through the undisturbed kelp landscape, he is overwhelmed with his smallness in this almost alien landscape. He is alone, but not for long. Mew’s poems range from conventional Victorian elegies to wild outpourings of loss, longing and fear of death. If you read her work to a random array of people who don’t know it (as I did the other day) then they may well liken it to Christina Rossetti, Thomas Hardy, D H Lawrence or (unkindly) ‘bad Philip Larkin’. Her most memorable and idiosyncratic poems include ‘Rooms’ (‘I remember rooms that have had their part/In the steady slowing down of the heart’) and ‘Fame’ (‘Sometimes in the over-heated house, but not for long,/Smirking and speaking rather loud,/ I see myself among the crowd’). Her work, writes Copus, was ‘unashamedly emotive’ and therefore ‘out of kilter with the ideals of the fashionable Imagists’. She was too traditional for some and too radical for others. A printer refused to set one of her poems, ‘Madeleine in Church’, because he thought it was blasphemous. She has ‘frequently been identified as a lesbian’, Copus notes, including by Penelope Fitzgerald in Charlotte Mew and Her Friends (1984). There is also a rumour that Mew ‘conducted an illicit affair with Thomas Hardy’.

Mew’s poems range from conventional Victorian elegies to wild outpourings of loss, longing and fear of death. If you read her work to a random array of people who don’t know it (as I did the other day) then they may well liken it to Christina Rossetti, Thomas Hardy, D H Lawrence or (unkindly) ‘bad Philip Larkin’. Her most memorable and idiosyncratic poems include ‘Rooms’ (‘I remember rooms that have had their part/In the steady slowing down of the heart’) and ‘Fame’ (‘Sometimes in the over-heated house, but not for long,/Smirking and speaking rather loud,/ I see myself among the crowd’). Her work, writes Copus, was ‘unashamedly emotive’ and therefore ‘out of kilter with the ideals of the fashionable Imagists’. She was too traditional for some and too radical for others. A printer refused to set one of her poems, ‘Madeleine in Church’, because he thought it was blasphemous. She has ‘frequently been identified as a lesbian’, Copus notes, including by Penelope Fitzgerald in Charlotte Mew and Her Friends (1984). There is also a rumour that Mew ‘conducted an illicit affair with Thomas Hardy’. In 2015, in The Limits of Critique, Rita Felski argued that critique, a term she uses to characterise the predominant institutionalised practices of interpretation, solicits the critic to adopt a stance and tone of ‘ferocious and blistering detachment’. The critic’s encounter with a text is driven by ‘desire to puncture illusions, topple idols and destroy divinities,’ that is both combative and paranoid. Towards the end of this book, Felski invokes Actor-Network Theory (ANT) as one possible way out from the uncomfortable corner that critique has backed us into. Felski’s 2020 book, Hooked: Art and Attachment, returns to this possibility: to demonstrate an intellectual and political alternative to the method of ‘critical reading’. This book extends Felski’s belief that criticism cannot fully account for broader questions of attachment: ‘What do works of art do? What do they set in motion? And to what are they linked or tie?’ Here, as elsewhere, one of Felski’s most convincing claims is that aesthetic relations always involve ‘more than power relations’.

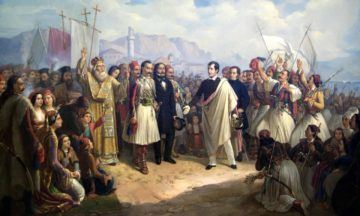

In 2015, in The Limits of Critique, Rita Felski argued that critique, a term she uses to characterise the predominant institutionalised practices of interpretation, solicits the critic to adopt a stance and tone of ‘ferocious and blistering detachment’. The critic’s encounter with a text is driven by ‘desire to puncture illusions, topple idols and destroy divinities,’ that is both combative and paranoid. Towards the end of this book, Felski invokes Actor-Network Theory (ANT) as one possible way out from the uncomfortable corner that critique has backed us into. Felski’s 2020 book, Hooked: Art and Attachment, returns to this possibility: to demonstrate an intellectual and political alternative to the method of ‘critical reading’. This book extends Felski’s belief that criticism cannot fully account for broader questions of attachment: ‘What do works of art do? What do they set in motion? And to what are they linked or tie?’ Here, as elsewhere, one of Felski’s most convincing claims is that aesthetic relations always involve ‘more than power relations’. Racked by fever, prone to fits of delirium, consumed by his last great passion – the liberation of

Racked by fever, prone to fits of delirium, consumed by his last great passion – the liberation of  Letter from Norbert to Bertha Wiener (July, 1925):

Letter from Norbert to Bertha Wiener (July, 1925): Like many readers, I began in early adulthood to keep a mental list of big books that I meant to tackle someday. Thanks to the passage of time and my dilatory nature, that list now includes some entries that I haven’t gotten around to for many years—in a few cases, a decade or more. One such book is Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), which I decided to read back in graduate school after taking a course that featured Smith’s earlier achievement, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). At the time, though, the book seemed just a bit too long, and every time I’ve picked it up since I’ve always been able to manufacture reasons for further delay.

Like many readers, I began in early adulthood to keep a mental list of big books that I meant to tackle someday. Thanks to the passage of time and my dilatory nature, that list now includes some entries that I haven’t gotten around to for many years—in a few cases, a decade or more. One such book is Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), which I decided to read back in graduate school after taking a course that featured Smith’s earlier achievement, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). At the time, though, the book seemed just a bit too long, and every time I’ve picked it up since I’ve always been able to manufacture reasons for further delay. In the years since the trailblazers of Odd Future distributed their music through Tumblr, many younger artists have used the social Web to find kindred creative spirits—both around the world and closer to home. The YBN hip-hop collective started in XBox Live group chats, and key members of the Bay Area group AG Club stumbled upon one another on Twitter. At the center of this movement is Brockhampton, a huge, perception-bending group with origins in Texas and branches as far off as Grenada and Belfast. The collective, conceived on a message board by its de-facto leader, the polymath Kevin Abstract, eventually ballooned to include more than a dozen rappers, singers, producers, and visual artists of various races, sexual orientations, and creative philosophies. The bohemian crew—which mixes Abstract’s high-school friends (JOBA, Merlyn Wood, and Matt Champion) with those he met online (bearface, Dom McLennon, Jabari Manwa, and Romil Hemnani)—set out to remake a pop paradigm, the boy band, in a way that reflected itself: multiracial, multinational, other.

In the years since the trailblazers of Odd Future distributed their music through Tumblr, many younger artists have used the social Web to find kindred creative spirits—both around the world and closer to home. The YBN hip-hop collective started in XBox Live group chats, and key members of the Bay Area group AG Club stumbled upon one another on Twitter. At the center of this movement is Brockhampton, a huge, perception-bending group with origins in Texas and branches as far off as Grenada and Belfast. The collective, conceived on a message board by its de-facto leader, the polymath Kevin Abstract, eventually ballooned to include more than a dozen rappers, singers, producers, and visual artists of various races, sexual orientations, and creative philosophies. The bohemian crew—which mixes Abstract’s high-school friends (JOBA, Merlyn Wood, and Matt Champion) with those he met online (bearface, Dom McLennon, Jabari Manwa, and Romil Hemnani)—set out to remake a pop paradigm, the boy band, in a way that reflected itself: multiracial, multinational, other.