Barbara Spindel in The Christian Science Monitor:

In high school, one of author Jess Zimmerman’s Internet usernames was Medusa. A self-described mythology nerd, her childhood copy of “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths” was well-worn. But as she recalls in her scorching collection of essays, “Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology,” she particularly identified with the snake-haired creature whose power originated in ugliness: The mere sight of Medusa could turn a man to stone. As a teenager who was profoundly insecure about her looks, Zimmerman writes that calling herself Medusa was “an attempt to recuse myself from the game of human attraction before anyone pointed out that I’d already lost.”

In high school, one of author Jess Zimmerman’s Internet usernames was Medusa. A self-described mythology nerd, her childhood copy of “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths” was well-worn. But as she recalls in her scorching collection of essays, “Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology,” she particularly identified with the snake-haired creature whose power originated in ugliness: The mere sight of Medusa could turn a man to stone. As a teenager who was profoundly insecure about her looks, Zimmerman writes that calling herself Medusa was “an attempt to recuse myself from the game of human attraction before anyone pointed out that I’d already lost.”

Mythology is rife with hideous female creatures. Many of them, like Medusa, have the face of a woman but other grotesque, unnatural body parts. The Sirens are half bird, half woman; Scylla’s lower half is a mass of snarling dogs; the Sphinx has the body of a lion and the wings of a bird. All of them pose grave dangers to male heroes.

That’s not the only thing they have in common. “All the stories about monstrous women, about creatures who are too gross, too angry, too devious, too grasping, too smart for their own good, are stories told by men,” Zimmerman notes, citing Ovid, Homer, Virgil, and Sophocles. They were intended to be cautionary tales, warning women not to overreach, but the author wonders what would happen if women were to stop reading them as warnings and instead embrace them as aspirations.

More here.

The pandemic is sweeping through India at a pace that has staggered scientists. Daily case numbers have exploded since early March: the government reported 273,810 new infections nationally on 18 April. High numbers in India have also helped drive global cases to a daily high of 854,855 in the past week, almost breaking a record set in January. Just months earlier, antibody data had suggested that many people in cities such as Delhi and Chennai had already been infected, leading some researchers to conclude that the worst of the pandemic

The pandemic is sweeping through India at a pace that has staggered scientists. Daily case numbers have exploded since early March: the government reported 273,810 new infections nationally on 18 April. High numbers in India have also helped drive global cases to a daily high of 854,855 in the past week, almost breaking a record set in January. Just months earlier, antibody data had suggested that many people in cities such as Delhi and Chennai had already been infected, leading some researchers to conclude that the worst of the pandemic

Adam S. Green in the Journal of Archaeological Research (h/t

Adam S. Green in the Journal of Archaeological Research (h/t  Steve Hahn in Boston Review:

Steve Hahn in Boston Review: Dilip Hiro in The Nation:

Dilip Hiro in The Nation: Philip Roth

Philip Roth Seth Rogen’s home sits on several wooded acres in the hills above Los Angeles, under a canopy of live oak and eucalyptus trees strung with outdoor pendants that light up around dusk, when the frogs on the grounds start croaking. I pulled up at the front gate on a recent afternoon, and Rogen’s voice rumbled through the intercom. “Hellooo!” He met me at the bottom of his driveway, which is long and steep enough that he keeps a golf cart up top “for schlepping big things up the driveway that are too heavy to walk,” he said, adding, as if bashful about coming off like the kind of guy who owns a dedicated driveway golf cart, “It doesn’t get a ton of use.” Rogen wore a beard, chinos, a cardigan from the Japanese brand Needles and Birkenstocks with marled socks — laid-back Canyon chic. He led me to a switchback trail cut into a hillside, which we climbed to a vista point. Below us was Rogen’s office; the house he shares with his wife, Lauren, and their 11-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Zelda; and the converted garage where they make pottery. I was one of the first people, it turns out, to see the place. “I haven’t had many people over,” Rogen said, “because we moved in during the pandemic.”

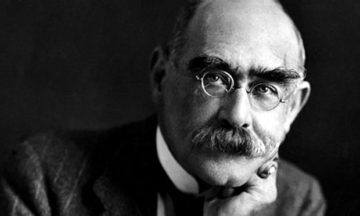

Seth Rogen’s home sits on several wooded acres in the hills above Los Angeles, under a canopy of live oak and eucalyptus trees strung with outdoor pendants that light up around dusk, when the frogs on the grounds start croaking. I pulled up at the front gate on a recent afternoon, and Rogen’s voice rumbled through the intercom. “Hellooo!” He met me at the bottom of his driveway, which is long and steep enough that he keeps a golf cart up top “for schlepping big things up the driveway that are too heavy to walk,” he said, adding, as if bashful about coming off like the kind of guy who owns a dedicated driveway golf cart, “It doesn’t get a ton of use.” Rogen wore a beard, chinos, a cardigan from the Japanese brand Needles and Birkenstocks with marled socks — laid-back Canyon chic. He led me to a switchback trail cut into a hillside, which we climbed to a vista point. Below us was Rogen’s office; the house he shares with his wife, Lauren, and their 11-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Zelda; and the converted garage where they make pottery. I was one of the first people, it turns out, to see the place. “I haven’t had many people over,” Rogen said, “because we moved in during the pandemic.” It is always tricky writing about Kipling. By the time of his death in 1936 his jingoism, with its babble about the “white man’s burden” in Africa, made many moderate souls feel queasy. Batchelor is too scrupulous a scholar to ignore what came after the Just So Stories – indeed he points out that within two years of the book’s publication the satirist Max Beerbohm was drawing Kipling as an imperial stooge, the diminutive bugle-blowing cockney lover of a blousy-looking Britannia.

It is always tricky writing about Kipling. By the time of his death in 1936 his jingoism, with its babble about the “white man’s burden” in Africa, made many moderate souls feel queasy. Batchelor is too scrupulous a scholar to ignore what came after the Just So Stories – indeed he points out that within two years of the book’s publication the satirist Max Beerbohm was drawing Kipling as an imperial stooge, the diminutive bugle-blowing cockney lover of a blousy-looking Britannia. The evenhanded approach of

The evenhanded approach of  I thought I was so clever. For a few days, anyway.

I thought I was so clever. For a few days, anyway. The first numbers that come to mind when thinking about Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland might be how much money the movie is raking in at the box office.

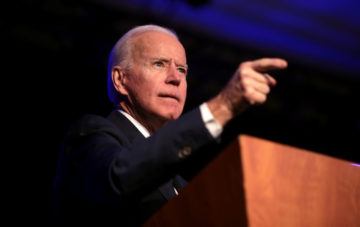

The first numbers that come to mind when thinking about Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland might be how much money the movie is raking in at the box office. I would like to stage a fight between two different accounts of the current political landscape—what’s been called the “post-truth” era, the infodemic, the end of democracy, or perhaps most accurately, the total shitshow of the now.

I would like to stage a fight between two different accounts of the current political landscape—what’s been called the “post-truth” era, the infodemic, the end of democracy, or perhaps most accurately, the total shitshow of the now. “W

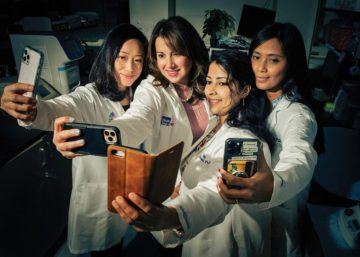

“W “It feels like a grew a new heart.” That’s what my best friend told me the day her daughter was born. Back then, I rolled my eyes at her new-mom corniness. But ten years and three kids of my own later, Emily’s words drift back to me as I ride a crammed elevator up to a laboratory in New York City’s

“It feels like a grew a new heart.” That’s what my best friend told me the day her daughter was born. Back then, I rolled my eyes at her new-mom corniness. But ten years and three kids of my own later, Emily’s words drift back to me as I ride a crammed elevator up to a laboratory in New York City’s