Dan Sperber in Psyche:

Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless.

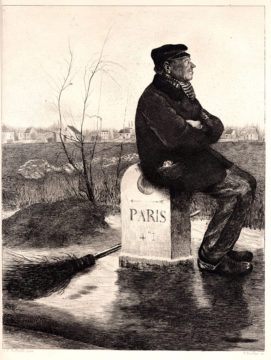

Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless.

The composition of the picture is peculiar: the left half, behind the man’s back, is occupied by a meagre leafless shrub, nondescript houses in the distance, and the broom on the ground. The man sitting on the milestone occupies the right half and is facing the edge of the frame rather than its centre. This picture elicits a sense of empathy for this humble worker who seems to be enjoying his rest but to have little else to look forward to. The spatial composition of the picture contributes, I want to argue, to its poignancy, and it does so in part because of an evolved psychological disposition, a disposition that humans are likely to share with many other animals.

More here.