Lydia Denworth in Scientific American:

What is found in a good conversation? It is certainly correct to say words—the more engagingly put, the better. But conversation also includes “eyes, smiles, the silences between the words,” as the Swedish author Annika Thor wrote. It is when those elements hum along together that we feel most deeply engaged with, and most connected to, our conversational partner, as if we are in sync with them. Like good conversationalists, neuroscientists at Dartmouth College have taken that idea and carried it to new places. As part of a series of studies on how two minds meet in real life, they reported surprising findings on the interplay of eye contact and the synchronization of neural activity between two people during conversation. In a paper published on September 14 in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA, the researchers suggest that being in tune with a conversational partner is good but that going in and out of alignment with them might be better.

What is found in a good conversation? It is certainly correct to say words—the more engagingly put, the better. But conversation also includes “eyes, smiles, the silences between the words,” as the Swedish author Annika Thor wrote. It is when those elements hum along together that we feel most deeply engaged with, and most connected to, our conversational partner, as if we are in sync with them. Like good conversationalists, neuroscientists at Dartmouth College have taken that idea and carried it to new places. As part of a series of studies on how two minds meet in real life, they reported surprising findings on the interplay of eye contact and the synchronization of neural activity between two people during conversation. In a paper published on September 14 in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA, the researchers suggest that being in tune with a conversational partner is good but that going in and out of alignment with them might be better.

Making eye contact has long been conceived as acting like a cohesive glue, connecting an individual to the person with whom they are talking. Its absence can signal social dysfunction. Similarly, the growing study of neural synchrony has focused on the positive aspects of alignment in brain activity between individuals.

In the new study, by using pupil dilation as a measure of synchrony during unstructured conversation, psychologist Thalia Wheatley and graduate student Sophie Wohltjen found that the moment of making eye contact marks a peak in shared attention—and not the beginning of a sustained period of locked gazes. Synchrony, in fact, drops sharply after looking into the eyes of your interlocutor and only begins to recover when you and that person look away from each other. “Eye contact is not eliciting synchrony; it’s disrupting it,” says Wheatley, senior author of the paper.

More here.

On a December morning in 1947 when three fellows at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study set out for the Third Circuit Court in Trenton, it was decided that the job of making sure that the brilliant but naively innocent logician Kurt Gödel didn’t say something intemperate at his citizenship hearing would fall to Albert Einstein. Economist Oscar Morgenstern would drive, Einstein rode shotgun, and a nervous Gödel sat in the back. With squibs of low winter light, both wave and particle, dappled across the rattling windows of Morgenstern’s car, Einstein turned back and asked, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” There had been no doubt that the philosopher had adequately studied, but as to whether it was proper to be fully honest was another issue. Less than two centuries before, and the signatories of the U.S. Constitution had supposedly crafted a document defined by separation of powers and coequal government, checks and balances, action and reaction. “The science of politics,” wrote Alexander Hamilton in “Federalist Paper No. 9,” “has received great improvement,” though as Gödel discovered, clearly not perfection. With a completism that only a Teutonic logician was capable of, Gödel had carefully read the foundational documents of American political theory, he’d poured over the Federalist Papers and the Constitution, and he’d made an alarming discovery.

On a December morning in 1947 when three fellows at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study set out for the Third Circuit Court in Trenton, it was decided that the job of making sure that the brilliant but naively innocent logician Kurt Gödel didn’t say something intemperate at his citizenship hearing would fall to Albert Einstein. Economist Oscar Morgenstern would drive, Einstein rode shotgun, and a nervous Gödel sat in the back. With squibs of low winter light, both wave and particle, dappled across the rattling windows of Morgenstern’s car, Einstein turned back and asked, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” There had been no doubt that the philosopher had adequately studied, but as to whether it was proper to be fully honest was another issue. Less than two centuries before, and the signatories of the U.S. Constitution had supposedly crafted a document defined by separation of powers and coequal government, checks and balances, action and reaction. “The science of politics,” wrote Alexander Hamilton in “Federalist Paper No. 9,” “has received great improvement,” though as Gödel discovered, clearly not perfection. With a completism that only a Teutonic logician was capable of, Gödel had carefully read the foundational documents of American political theory, he’d poured over the Federalist Papers and the Constitution, and he’d made an alarming discovery. Testosterone’s wide-reaching effects occur not just in the human body, but across society, powering acts of aggression, violence, and the large disparity in their commission between men and women, according to Harvard human evolutionary biologist

Testosterone’s wide-reaching effects occur not just in the human body, but across society, powering acts of aggression, violence, and the large disparity in their commission between men and women, according to Harvard human evolutionary biologist  Sergio Ramírez, Nicaragua’s best-known living writer, hero of the Sandinista revolution, and former vice-president of the volcanic Central American nation, has lived through both tougher times and duller publicity tours.

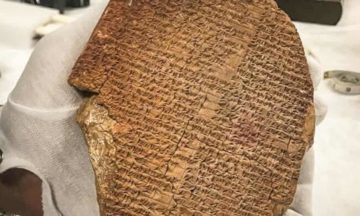

Sergio Ramírez, Nicaragua’s best-known living writer, hero of the Sandinista revolution, and former vice-president of the volcanic Central American nation, has lived through both tougher times and duller publicity tours. A 3,600-year-old tablet showing part of the Epic of Gilgamesh will be formally handed back to

A 3,600-year-old tablet showing part of the Epic of Gilgamesh will be formally handed back to  Allison Draper loved anatomy class. As a first-year medical student at the University of Miami, she found the language clear, precise, functional. She could look up the Latin term for almost any body part and get an idea of where it was and what it did. The flexor carpi ulnaris, for instance, is a muscle in the forearm that bends the wrist — exactly as its name suggests. Then one day she looked up the pudendal nerve, which provides sensation to the vagina and vulva, or outer female genitalia. The term derived from the Latin verb pudere: to be ashamed. The shame nerve, Ms. Draper noted: “I was like, What? Excuse me?”

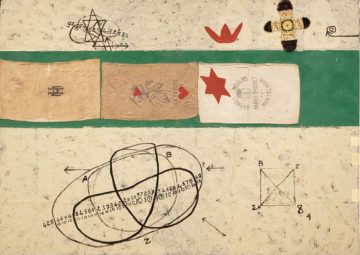

Allison Draper loved anatomy class. As a first-year medical student at the University of Miami, she found the language clear, precise, functional. She could look up the Latin term for almost any body part and get an idea of where it was and what it did. The flexor carpi ulnaris, for instance, is a muscle in the forearm that bends the wrist — exactly as its name suggests. Then one day she looked up the pudendal nerve, which provides sensation to the vagina and vulva, or outer female genitalia. The term derived from the Latin verb pudere: to be ashamed. The shame nerve, Ms. Draper noted: “I was like, What? Excuse me?” MYTHOLOGIES RARELY SERVE the artists who inspire them. Ouattara Watts has now entered his fifth decade of painting. His oeuvre consists of the large-to-monumental canvases he has been making prodigiously for forty-five years, alongside lesser-known watercolors, gouaches, drawings, and collages. Over time, he has developed an expansive and wildly complex visual language. It is also unabashedly joyful, even beautiful, insisting on a universal purpose for painting. More than a body, his is a forest of works, too vast, dense, and important to be detoured by an origin story. And yet the origin story persists, making a circuitous route around but rarely through the work and confounded, perhaps, by some minor confusion over the artist’s name: He was born Bakari Ouattara (in the Ivorian capital Abidjan), nicknamed Ouatts (in his youth) and later Ouatt (in Paris), became known as Ouattara Watts (in New York), and is referred to (almost everywhere) as simply Ouattara.

MYTHOLOGIES RARELY SERVE the artists who inspire them. Ouattara Watts has now entered his fifth decade of painting. His oeuvre consists of the large-to-monumental canvases he has been making prodigiously for forty-five years, alongside lesser-known watercolors, gouaches, drawings, and collages. Over time, he has developed an expansive and wildly complex visual language. It is also unabashedly joyful, even beautiful, insisting on a universal purpose for painting. More than a body, his is a forest of works, too vast, dense, and important to be detoured by an origin story. And yet the origin story persists, making a circuitous route around but rarely through the work and confounded, perhaps, by some minor confusion over the artist’s name: He was born Bakari Ouattara (in the Ivorian capital Abidjan), nicknamed Ouatts (in his youth) and later Ouatt (in Paris), became known as Ouattara Watts (in New York), and is referred to (almost everywhere) as simply Ouattara.

W

W Recently I was sent an article about “

Recently I was sent an article about “ Humans have long wondered why we sleep. A well-rested prehistoric mind probably pondered the question, long before Galileo thought to predict the period of the pendulum or to understand how fast objects fall. Why must we put ourselves into this potentially endangering state, one that consumes about a third of our adult lives and even more of our childhood? And we don’t do it grudgingly – why do we, along with dogs, lions and virtually every other animal, apparently enjoy it? Unlike measuring the period of the pendulum, scientists would have to wait much longer to obtain reliable answers, since it’s not so easy to sleep while strangers watch. Doing so involves building sleep disorder clinics for humans and elaborate structures such as platypusariums to observe the REM (rapid eye movement) repose of platypuses.

Humans have long wondered why we sleep. A well-rested prehistoric mind probably pondered the question, long before Galileo thought to predict the period of the pendulum or to understand how fast objects fall. Why must we put ourselves into this potentially endangering state, one that consumes about a third of our adult lives and even more of our childhood? And we don’t do it grudgingly – why do we, along with dogs, lions and virtually every other animal, apparently enjoy it? Unlike measuring the period of the pendulum, scientists would have to wait much longer to obtain reliable answers, since it’s not so easy to sleep while strangers watch. Doing so involves building sleep disorder clinics for humans and elaborate structures such as platypusariums to observe the REM (rapid eye movement) repose of platypuses. It’s not often that a shotgun-wielding thief and killer comes to be seen as possessing a moral core. But then it’s not often that you have a character like Omar Little. Or an actor like Michael K Williams to bring him to life. Or a TV series like The Wire that allowed both character and actor to breathe.

It’s not often that a shotgun-wielding thief and killer comes to be seen as possessing a moral core. But then it’s not often that you have a character like Omar Little. Or an actor like Michael K Williams to bring him to life. Or a TV series like The Wire that allowed both character and actor to breathe. When I left Stanford to join Google as an AI research scientist, I “went across the street,” as the saying went. I had been a young assistant professor, first at Georgia Tech and then at Stanford, doing research that was partially funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). At one point, I brought up the ethical issues of researching surveillance technology with the DARPA program manager, but frankly, raising ethical concerns in such a competitive environment felt a bit like labeling myself a troublemaker.

When I left Stanford to join Google as an AI research scientist, I “went across the street,” as the saying went. I had been a young assistant professor, first at Georgia Tech and then at Stanford, doing research that was partially funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). At one point, I brought up the ethical issues of researching surveillance technology with the DARPA program manager, but frankly, raising ethical concerns in such a competitive environment felt a bit like labeling myself a troublemaker. For almost two decades, I have been attempting to understand the origins and drivers of the

For almost two decades, I have been attempting to understand the origins and drivers of the  The Irish writer Colm Tóibín is a busy man. Since he published his first novel, “

The Irish writer Colm Tóibín is a busy man. Since he published his first novel, “