Category: Recommended Reading

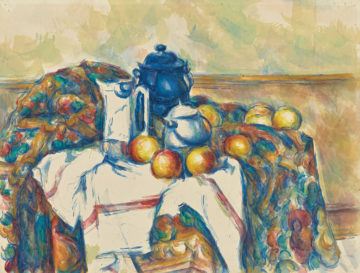

Cézanne Drawing

Paul Galvez at Artforum:

I’M NOT ONE FOR FLATTERY and hyperbole, especially when reacting to exhibitions. There is already enough sycophancy to go around on social media—even in the feeds of those who should know better. I am therefore going against every fiber of my being when I say that the Cézanne drawing show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art is unequivocally a once-in-a-generation not-to-be-missed event.

I’M NOT ONE FOR FLATTERY and hyperbole, especially when reacting to exhibitions. There is already enough sycophancy to go around on social media—even in the feeds of those who should know better. I am therefore going against every fiber of my being when I say that the Cézanne drawing show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art is unequivocally a once-in-a-generation not-to-be-missed event.

Why the superlatives? First, there is the sheer volume: more than 250 works on paper, mostly drawings and watercolors, some of which may never be seen again (or will have faded by the time they are). They will almost certainly never be together again in my lifetime. Then there is the sheer quality (another word that does not easily cross the lips). Usually, even the most carefully curated show has at least one turkey, a work that for whatever reason doesn’t fit, looks off, is unappealing, or appears to be by a different artist altogether.

more here.

Steven Pinker, Stephen Hsu and Dalton Conley: Can Genius Be Genetically Engineered?

Bezos as Novelist

Mark McGurl at The Paris Review:

The Testing of Luther Albright (2005) and Traps (2013) are perfectly good novels if one has a taste for it. The second thing that needs to be noted about them is that, after her divorce from Jeff Bezos, founder and controlling shareholder of Amazon, their author is the richest woman in the world, or close enough, worth in excess (as I write these words) of $60 billion, mostly from her holdings of Amazon stock. She is no doubt the wealthiest published novelist of all time by a factor of … whatever, a high number. Compared to her, J. K. Rowling is still poor.

The Testing of Luther Albright (2005) and Traps (2013) are perfectly good novels if one has a taste for it. The second thing that needs to be noted about them is that, after her divorce from Jeff Bezos, founder and controlling shareholder of Amazon, their author is the richest woman in the world, or close enough, worth in excess (as I write these words) of $60 billion, mostly from her holdings of Amazon stock. She is no doubt the wealthiest published novelist of all time by a factor of … whatever, a high number. Compared to her, J. K. Rowling is still poor.

It’s the garishness of the latter fact that makes the high quality of her fiction so hard to credit, so hard to know what to do with except ignore it in favor of the spectacle of titanic financial power and the gossipy blather it carries in train. How can the gifts she has given the world as an artist begin to compare with those she has been issuing as hard cash? Of late it has been reported that Bezos, now going by the name MacKenzie Scott, has been dispensing astonishingly large sums of money very fast, giving it to worthy causes, although not as fast as she has been making it as a holder of stock in her ex’s company.

more here.

The Elizabeth Holmes Line

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

ELIZABETH HOLMES SAYS she is a battered woman. Holmes, the former CEO of Theranos, a company that claimed to be able to perform complex diagnostic tests with just a pinprick of blood, is now alleging that she lied and defrauded investors and employees because she was under the control of her then partner and Theranos executive Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani. “Mr. Balwani is more than Elizabeth Holmes’ co-defendant,” according to the pleading Holmes’s legal team filed last year asking the U.S. District Court for Northern California to try the pair separately. It goes on to say that “for over a decade, Ms. Holmes and Mr. Balwani had an abusive intimate-partner relationship, in which Mr. Balwani exercised psychological, emotional, and [redacted] over Ms. Holmes.” Such is the fear that Balwani invokes in Holmes, we are told, that she cannot effectively participate in her own defense if Balwani is in the courtroom. Their argument succeeded in separating the two trial proceedings. The trial of Holmes for fraud began August 31; Balwani’s trial is expected to start next year.

ELIZABETH HOLMES SAYS she is a battered woman. Holmes, the former CEO of Theranos, a company that claimed to be able to perform complex diagnostic tests with just a pinprick of blood, is now alleging that she lied and defrauded investors and employees because she was under the control of her then partner and Theranos executive Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani. “Mr. Balwani is more than Elizabeth Holmes’ co-defendant,” according to the pleading Holmes’s legal team filed last year asking the U.S. District Court for Northern California to try the pair separately. It goes on to say that “for over a decade, Ms. Holmes and Mr. Balwani had an abusive intimate-partner relationship, in which Mr. Balwani exercised psychological, emotional, and [redacted] over Ms. Holmes.” Such is the fear that Balwani invokes in Holmes, we are told, that she cannot effectively participate in her own defense if Balwani is in the courtroom. Their argument succeeded in separating the two trial proceedings. The trial of Holmes for fraud began August 31; Balwani’s trial is expected to start next year.

That is not the end of it. Holmes is also apparently planning to allege that she is not guilty because Balwani effectively made her lie by using the manipulative power he had over her. Holmes’s lies to investors, her subterfuge with employees, and her claims that Theranos had developed game-changing technology all took place, we are to believe, because of intimate-partner abuse. As one law professor writing on his blog put it, “I’ve been in this business for a long time and this is the first time I’ve heard of the mental disease or defect defense being used in a securities fraud case.”

The more common use of the defense is in criminal cases where a defendant facing criminal charges must prove that they cannot be criminally liable for an act because of a “mental disease or defect” which then prevented them from being able to “appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his acts.”

More here.

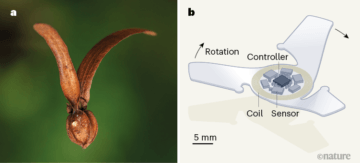

Seed-inspired vehicles take flight

E. Farrell Helbling in Nature:

In a paper in Nature, Kim et al.1 report 3D fliers that are inspired by the passive, helicopter-style wind-dispersal mechanism of certain seeds. The adopted production processes enable the rapid parallel fabrication of many fliers and permit the integration of simple electronic circuits using standard silicon-on-insulator techniques. Tuning the design parameters — such as the diameter, porosity and wing type — generates beneficial interactions between the devices and the surrounding air. Such interactions lower the terminal velocity of the fliers, increase air resistance and improve stability by inducing rotational motion. When combined with complex integrated circuits, these devices could form dynamic sensor networks for environmental monitoring, wireless communication nodes or various other technologies based on the network of Internet-connected devices called the Internet of Things.

In a paper in Nature, Kim et al.1 report 3D fliers that are inspired by the passive, helicopter-style wind-dispersal mechanism of certain seeds. The adopted production processes enable the rapid parallel fabrication of many fliers and permit the integration of simple electronic circuits using standard silicon-on-insulator techniques. Tuning the design parameters — such as the diameter, porosity and wing type — generates beneficial interactions between the devices and the surrounding air. Such interactions lower the terminal velocity of the fliers, increase air resistance and improve stability by inducing rotational motion. When combined with complex integrated circuits, these devices could form dynamic sensor networks for environmental monitoring, wireless communication nodes or various other technologies based on the network of Internet-connected devices called the Internet of Things.

So far, research into collectives of aerial vehicles has been focused on active systems, including quadcopters2,3 and insect- or bird-inspired robotic platforms4. Active systems have the benefit of being able to move independently through their environment. However, their practical applications are limited because of the size and safety concerns of larger platforms (such as quadcopters, which have a wingspan of about 50 centimetres) and lack of onboard electronics and power supplies that enable autonomous locomotion in real-world settings in the case of smaller platforms (with a wingspan of roughly 3.5 cm)5. Furthermore, because these research platforms5–7 are highly specialized and assembled by hand, they cannot be used for studies of collective systems.

More here.

Friday Poem

Taos Mountain

“Though the mountains fall into the sea”

describes the faith of some, but the mountains do not move

whatever we say, whatever saints and shamans do.

It is their indifference to us that makes them sacred.

On the edge of this flat town, beyond the pueblo,

the black mountain rises, a reference point

to every human moment, utterly silent.

No one climbs this mountain, there are no trails,

because the place is holy: it does not exist to serve us,

it is not meant to please us, it simply is,

and in this way it is a god.

Mountains do not move, and that is their mountainness.

Geologists can say they have moved over time,

but not in human time. This mountain outside my window

has always been there: when the pueblo was built,

when the Spanish came and were driven away,

when the missionaries returned, then Americans and Apache.

The mountain abides. That is its power

in imagination and worship. Were it to respond

to our prayers and dances it would cease to be itself.

Its silence is what we listen to, and the reason

it is a source of strength. I will not pretend

it whispers secrets to me or that I have pleased it.

The mountain is black even in sunlight or capped with snow.

It may have its back turned to the human

like an inscrutable mother in a shawl.

There are no signs given us to read

and any language to describe it is our own.

The fact of the mountain is our bare and only creed.

by Stephen Hollaway

from the Ecotheo Review

Thursday, September 23, 2021

Richard Neutra’s Architectural Vanishing Act

Alex Ross at The New Yorker:

On December 15, 1929, Dr. Philip M. Lovell, the imperiously eccentric health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, invited readers to tour his ultramodern new home, at 4616 Dundee Drive, in the hills of Los Feliz. On a page crowded with ads promoting quack cures for “chronic constipation” and “sagging flabby chins,” Lovell announced three days of open houses, adding that “Mr. Richard T. Neutra, architect who designed and supervised the construction . . . will conduct the audience from room to room.” Neutra’s middle initial was actually J., but this recent Austrian immigrant, thirty-seven years old and underemployed, had little reason to complain: he was being launched as a pioneer of American modernist architecture. Thousands of people took the tour; striking photographs were published. Three years later, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the codifiers of the International Style, hailed Neutra’s work as “stylistically the most advanced house built in America since the War.”

On December 15, 1929, Dr. Philip M. Lovell, the imperiously eccentric health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, invited readers to tour his ultramodern new home, at 4616 Dundee Drive, in the hills of Los Feliz. On a page crowded with ads promoting quack cures for “chronic constipation” and “sagging flabby chins,” Lovell announced three days of open houses, adding that “Mr. Richard T. Neutra, architect who designed and supervised the construction . . . will conduct the audience from room to room.” Neutra’s middle initial was actually J., but this recent Austrian immigrant, thirty-seven years old and underemployed, had little reason to complain: he was being launched as a pioneer of American modernist architecture. Thousands of people took the tour; striking photographs were published. Three years later, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the codifiers of the International Style, hailed Neutra’s work as “stylistically the most advanced house built in America since the War.”

more here.

Revising Edward Said’s Self-Image

Bruce Robbins at n+1:

THE ARC THAT SAID HIMSELF gave to his life is not entirely reliable. He tells the story of withdrawing from Foucault and “the kind of anti-historical and starkly theoretical position I seemed to be advancing in Beginnings.” But James Clifford made it clear in an early review that Orientalism was already torn by conflicting commitments for as well as against humanism, and as Brennan notes, those conflicts are even apparent three years earlier in Beginnings itself. Indeed, at the very beginning of his career, when “Said was quickly becoming known as the apostle of ‘theory,’” Brennan declares that “the thought horrified him.” It makes little sense, then, to think of Said as riding the theory wave and then jumping off. What he got from theory’s reversal of text and critic was the conviction that “criticism, not necessarily fiction, was where the deepest cultural recesses of society were laid bare”—in other words, that the work of the critic mattered in the world and to the world. This commitment remained consistent throughout his career, whatever his take on Foucault and company, and it’s one reason why his fellow critics came to embrace him, despite political and theoretical differences.

THE ARC THAT SAID HIMSELF gave to his life is not entirely reliable. He tells the story of withdrawing from Foucault and “the kind of anti-historical and starkly theoretical position I seemed to be advancing in Beginnings.” But James Clifford made it clear in an early review that Orientalism was already torn by conflicting commitments for as well as against humanism, and as Brennan notes, those conflicts are even apparent three years earlier in Beginnings itself. Indeed, at the very beginning of his career, when “Said was quickly becoming known as the apostle of ‘theory,’” Brennan declares that “the thought horrified him.” It makes little sense, then, to think of Said as riding the theory wave and then jumping off. What he got from theory’s reversal of text and critic was the conviction that “criticism, not necessarily fiction, was where the deepest cultural recesses of society were laid bare”—in other words, that the work of the critic mattered in the world and to the world. This commitment remained consistent throughout his career, whatever his take on Foucault and company, and it’s one reason why his fellow critics came to embrace him, despite political and theoretical differences.

more here.

Timothy Brennan on Edward Said, with Kai Bird

Possible interruption to 3QD postings today

We will be switching over to new servers today, Thursday, September 23, and this means we may not be able to post new items for a day or possibly longer. Thanks for your patience, and we’ll make the interruption as short as possible.

We will be switching over to new servers today, Thursday, September 23, and this means we may not be able to post new items for a day or possibly longer. Thanks for your patience, and we’ll make the interruption as short as possible.

Yours, Abbas

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

Turning Cadavers Into Compost

Lisa Wells at Harper’s Magazine:

He died the day after Christmas. His loved ones washed and anointed his body and kept vigil at his bedside. “He looked like a king,” Jenifer told me. “He was really, really beautiful.” She showed me a few photos. His body had been laid atop a hemp shroud and covered from the neck down in a layer of dried herbs and flower petals. Bouquets of lavender and tree fronds wreathed his head, and a ladybug pendant on a beaded string lay across his brow like a diadem. Only his bearded face was exposed, wearing the peaceful, inscrutable expression of the dead. He did look like a king, or like a woodland deity out of Celtic mythology—his gauze-wrapped neck the only evidence of his life as a mortal.

He died the day after Christmas. His loved ones washed and anointed his body and kept vigil at his bedside. “He looked like a king,” Jenifer told me. “He was really, really beautiful.” She showed me a few photos. His body had been laid atop a hemp shroud and covered from the neck down in a layer of dried herbs and flower petals. Bouquets of lavender and tree fronds wreathed his head, and a ladybug pendant on a beaded string lay across his brow like a diadem. Only his bearded face was exposed, wearing the peaceful, inscrutable expression of the dead. He did look like a king, or like a woodland deity out of Celtic mythology—his gauze-wrapped neck the only evidence of his life as a mortal.

On the third day of their vigil, Jenifer felt his spirit go.

Amigo Bob joined nine other pioneers at the Greenhouse on the cusp of the New Year: the first humans in the world to be legally composted.

more here.

Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies Is An Amorphous, Disquieting Novel

Leo Robson at The New Statesman:

The one thing you can say for sure about Katie Kitamura’s wonderfully sly new novel – the follow-up to her 2017 breakthrough A Separation, and one of Barack Obama’s summer reading picks – is that it offers a portrait of limbo. The unnamed narrator, a Japanese woman raised in Europe, has accepted a one-year contract as an interpreter at the International Criminal Court – identified only as “the Court” – in The Hague. The book’s title – which, like that of its predecessor, rejects the firmness of the definite article – refers to the relationship one might ideally have with language, spaces, customs, other people, one’s own emotions, the past. It’s unclear, at least at first, to what degree the character’s own failure to achieve this state herself is a product of temperament or circumstances – whether she is simply adjusting, or whether this is how she always presents, and negotiates, the world.

The one thing you can say for sure about Katie Kitamura’s wonderfully sly new novel – the follow-up to her 2017 breakthrough A Separation, and one of Barack Obama’s summer reading picks – is that it offers a portrait of limbo. The unnamed narrator, a Japanese woman raised in Europe, has accepted a one-year contract as an interpreter at the International Criminal Court – identified only as “the Court” – in The Hague. The book’s title – which, like that of its predecessor, rejects the firmness of the definite article – refers to the relationship one might ideally have with language, spaces, customs, other people, one’s own emotions, the past. It’s unclear, at least at first, to what degree the character’s own failure to achieve this state herself is a product of temperament or circumstances – whether she is simply adjusting, or whether this is how she always presents, and negotiates, the world.

more here.

The 2014 Edward Said Memorial Lecture with Dr. Judith Butler

Field Notes of a Sentence Watcher

Richard Hughes Gibson in The Hedgehog Review:

The historian Joe Moran begins his 2018 style guide, First You Write a Sentence, by outlining a comic routine unfortunately familiar to many of us:

The historian Joe Moran begins his 2018 style guide, First You Write a Sentence, by outlining a comic routine unfortunately familiar to many of us:

First I write a sentence. I get a tickle of an idea for how the words might come together, like an angler feeling a tug on the rod’s line. Then I sound out the sentence in my head. Then I tap it on my keyboard, trying to recall its shape. Then I look at it and say it aloud, to see if it sings. Then I tweak, rejig, shave off a syllable, swap a word for a phrase or phrase for a word. Then I sit it next to other sentences to see how it behaves in company. And then I delete it all and start again.

(This process has in fact already played out several times in the very piece that you are reading, albeit with one twist: rather than deleting the false starts, I have stowed them at the bottom of the page in hopes that they might be of use later on.) Moran goes on to point out that, aside from sleeping, writing sentences constitutes the biggest slice in the pie chart of his life. You can easily see why: On this account, “writing” a sentence is an evolutionary process in which generations of imperfectly adapted sentences arise, survive numerous trials, and settle into a potential habitat, only to die off again and again, sometimes dooming the entire ecosystem in the process, all in the service of formulating the fittest expression.

More here.

Biologists Rethink the Logic Behind Cells’ Molecular Signals

Philip Ball in Quanta:

Back in 2000, when Michael Elowitz of the California Institute of Technology was still a grad student at Princeton University, he accomplished a remarkable feat in the young field of synthetic biology: He became one of the first to design and demonstrate a kind of functioning “circuit” in living cells. He and his mentor, Stanislas Leibler, inserted a suite of genes into Escherichia coli bacteria that induced controlled swings in the cells’ production of a fluorescent protein, like an oscillator in electronic circuitry.

Back in 2000, when Michael Elowitz of the California Institute of Technology was still a grad student at Princeton University, he accomplished a remarkable feat in the young field of synthetic biology: He became one of the first to design and demonstrate a kind of functioning “circuit” in living cells. He and his mentor, Stanislas Leibler, inserted a suite of genes into Escherichia coli bacteria that induced controlled swings in the cells’ production of a fluorescent protein, like an oscillator in electronic circuitry.

It was a brilliant illustration of what the biologist and Nobel laureate François Jacob called the “logic of life”: a tightly controlled flow of information from genes to the traits that cells and other organisms exhibit.

But this lucid vision of circuit-like logic, which worked so elegantly in bacteria, too often fails in more complex cells.

More here.

Mark Blyth: The system increasingly works only for the uber-wealthy

Mark Blyth in The Guardian:

I travelled to New York City in August for the first time since the pandemic began, to visit friends who had just bought their first home. They are firmly upper-middle class and in their 40s. They took out a mortgage for $1.5m (£1.1m) to buy a place in a Brooklyn neighbourhood that was regarded until recently as an area immune to gentrification. So far, so typical. Asset ownership comes late these days.

I travelled to New York City in August for the first time since the pandemic began, to visit friends who had just bought their first home. They are firmly upper-middle class and in their 40s. They took out a mortgage for $1.5m (£1.1m) to buy a place in a Brooklyn neighbourhood that was regarded until recently as an area immune to gentrification. So far, so typical. Asset ownership comes late these days.

On the second day of my visit I saw a group of twenty- and thirtysomethings sitting together in a local park (of the type illuminated by sodium lights to discourage drug dealing). They had gathered around a banner announcing a meeting of the local tenants’ rights union. Almost every member of the group looked as if they could have featured in the pages of an Ivy League magazine. All bar one were white. Their neighbourhood was not.

I asked my host to explain this. She said real-estate investors were buying up single family homes, bulldozing them and building slick new apartment blocks. Given the stagnant supply of housing and the increasing demand for places to live, local rents were now “crazy”, and relatively wealthy residents were forming tenants’ unions. “Housing is now an asset class for the uber-rich,” she said. “What do you expect?”

We’ve all got used to the claim that housing is now an asset class, but few of us really think through what that means, or how we got here.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder: The Second Quantum Revolution

Wednesday Poem

First Milk

After all that birth, the legs you’ve used your whole life

are now wobbly & the lake where your son used to swim

trickles from between them. The spaces between your fingers

feel sticky. The first thing the baby does is search for the warmth

of you, his face a small suction cup for the mounds you’ve been

building. Those first golden drops, thick as honey, spill from you

& the nurse rushes to catch them with a plastic spoon. God forbid

they soak your hospital gown or run down your rib cage. Once, you were

a girl with two breasts like the smallest constellation, an incomplete ellipsis.

Today, they find new purpose. Today they are nourishment & comfort,

food, water, some kind of magic. They work so hard after years

of thinking themselves merely decorative.

by Danni Quintos

from Poetry magazine, September, 2021

A meander around many circulatory systems

Henry Nicholls in Nature:

Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it.

Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it.

Enter zoologist Bill Schutt. His book Pump refuses to tie the heart off from the circulatory system, and instead uses it to explore how multicellular organisms have found various ways to solve the same fundamental challenge: satisfying the metabolic needs of cells that are beyond the reach of simple diffusion. He writes of the co-evolution of the circulatory and respiratory systems: “They cooperate, they depend on each other, and they are basically useless by themselves.” At his best, Schutt guides us on a journey from the origin of the first contractile cells more than 500 million years ago to the emergence of vertebrates, not long afterwards. He takes in, for example, horseshoe crabs, their blood coloured blue by the presence of the copper-based oxygen-transport protein haemocyanin (equivalent to humans’ iron-based haemoglobin).

We learn that insects, lacking a true heart, have a muscular dorsal vessel that bathes their tissues in blood-like haemolymph. Earthworms, too, are heartless but with a more complex arrangement of five pairs of contractile vessels. Squid and other cephalopods have three distinct hearts. The are plenty of zoological nuggets to enjoy along the way. The tubular heart of a sea squirt, for instance, contains pacemaker-like cells that enable it to pump in one direction and then the other. Some creatures need masses of oxygen, others little, leading to more diversity. The plethodontids (a group of salamanders) have neither lungs nor gills, he explains: their relatively small oxygen requirements are met by diffusion through the skin.

More here.