Kumari

Dear Kumari,

I, of course, do not know if Kumari was really your name,

It became a custom in the Gulf to change the name of the servant upon arrival,

The mama says to you, “Your name is Maryam/Fatima/Kumari/Chandra,”

Even before she gives you your cotton apron,

The same apron that the previous Kumari used

Before she ran away

And became free

Crowded in a single room with ten others

Watching their pictures on the walls

Fading under the air conditioners.

Kumari,

They may talk to you in English

And give you your own room,

But they will dress you in a pink uniform,

For the concubine is no longer required to seduce.

Or they may talk to you in Arabic and the language of fingers,

That which depends on hand signs in some days,

Or on slapping your cheeks in others.

You might have to help the son

Discover his sexual desires,

Or even sacrifice

For the father’s bodily failures.

In both cases, do not run to the police station,

From there all fathers and sons come.

Kumari,

You must cut your hair regularly,

Mama might get angry one day

And claim your braid as a rope in her hand.

Write all the songs that you love in a notebook,

No forgotten songs can be found there.

Get angry, Kumari,

Hang yourself with the clothesline,

Use your knife outside the kitchen,

Teach the Mama and the Baba and the Bacha a lesson,

Let them create all those myths about your gods

Who ask you in your dreams

For some Khaleeji blood

To feed the belly of history.

Run, Kumari, run

And steal everything you find;

A ghost gotta act like one.

by Mona Kareem

from What I Sleep for Today

Publisher دار نوفا بلس للنشر والتوزيع)

(House Nova Plus Publishing and Distribution), Kuwait, 2016

Translation: 2016, Saqer A. Almarri

from: Jadaliyya, Ezine, January

Norm Macdonald was best known for

Norm Macdonald was best known for  Thirty years ago this month,

Thirty years ago this month,  I have a friend who studied the history of fascism. She gets angry when people call Trump (or some other villain du jour) fascist. “Words have meanings! Fascism isn’t just any right-winger you dislike!” Maybe she takes this a little too far; by a strict definition, she’s not even sure Franco qualifies.

I have a friend who studied the history of fascism. She gets angry when people call Trump (or some other villain du jour) fascist. “Words have meanings! Fascism isn’t just any right-winger you dislike!” Maybe she takes this a little too far; by a strict definition, she’s not even sure Franco qualifies. A

A Polachek’s career started with guys and guitars. She co-founded the indie band Chairlift when she was in college, in the early two-thousands, and the group quickly reached a steady level of afternoon-set-at-a-festival success. But “Pang,” a sumptuous avant-pop record about the ecstatic terrors of love, had inspired a fervent new following. Instead of being the lead singer of a band, Polachek was now an alt-pop diva whose fans wrote things like “omfg i’m gonna cry and pee yes queen” on Instagram and showed up to gigs in leather and mesh. (The phrase “bunny is a rider” was printed on white cotton thongs; they sold out in every size.) Polachek, who has also written songs for other performers—including “No Angel,” a track on Beyoncé’s self-titled album, from 2013—is as stylized as a Top Forty artist, but she has an experimental aesthetic, tending toward the esoteric. The visuals for “Pang” were partly inspired by the mid-twentieth-century American illustrator Eyvind Earle and the seventeenth-century engraver Jacques Hurtu. She has co-directed several of her frequently surreal music videos with her boyfriend, the visual artist Matt Copson.

Polachek’s career started with guys and guitars. She co-founded the indie band Chairlift when she was in college, in the early two-thousands, and the group quickly reached a steady level of afternoon-set-at-a-festival success. But “Pang,” a sumptuous avant-pop record about the ecstatic terrors of love, had inspired a fervent new following. Instead of being the lead singer of a band, Polachek was now an alt-pop diva whose fans wrote things like “omfg i’m gonna cry and pee yes queen” on Instagram and showed up to gigs in leather and mesh. (The phrase “bunny is a rider” was printed on white cotton thongs; they sold out in every size.) Polachek, who has also written songs for other performers—including “No Angel,” a track on Beyoncé’s self-titled album, from 2013—is as stylized as a Top Forty artist, but she has an experimental aesthetic, tending toward the esoteric. The visuals for “Pang” were partly inspired by the mid-twentieth-century American illustrator Eyvind Earle and the seventeenth-century engraver Jacques Hurtu. She has co-directed several of her frequently surreal music videos with her boyfriend, the visual artist Matt Copson. Covid has caused a deep crisis in the already suffering developing world, which contains nearly half of all humanity. And this will have serious implications for the future of the world economy and political order. Initially, Covid was something of a rich country’s disease. It started in industrial China and spread to places like the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom. But now none of the wealthiest countries falls within the top 10 worst-hit countries in terms of Covid deaths per capita. In the US, Covid has gone from the leading cause of death to seventh place in just over a year.

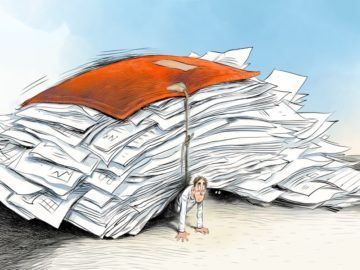

Covid has caused a deep crisis in the already suffering developing world, which contains nearly half of all humanity. And this will have serious implications for the future of the world economy and political order. Initially, Covid was something of a rich country’s disease. It started in industrial China and spread to places like the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom. But now none of the wealthiest countries falls within the top 10 worst-hit countries in terms of Covid deaths per capita. In the US, Covid has gone from the leading cause of death to seventh place in just over a year. Research articles in the life sciences are more ambitious than ever. The amount of data in high-impact journals has doubled over 20 years

Research articles in the life sciences are more ambitious than ever. The amount of data in high-impact journals has doubled over 20 years September 14, 2021, marked the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, the Florentine author of the world’s most renowned and masterful of all poems, The Divine Comedy. Not only did this poem have a marked impact on European vernacular languages in its notable departure from Latin, it also transformed how we understand the relationships among perpetrators, victims, and witnesses of violence. But more than this: it is perhaps with Dante that we really began to imagine what Hell looked like, which in turn demanded a revolution in how we understood the wretchedness of life, the fate of the sinful, and the path out through an all too earthly call to love and poetry.

September 14, 2021, marked the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, the Florentine author of the world’s most renowned and masterful of all poems, The Divine Comedy. Not only did this poem have a marked impact on European vernacular languages in its notable departure from Latin, it also transformed how we understand the relationships among perpetrators, victims, and witnesses of violence. But more than this: it is perhaps with Dante that we really began to imagine what Hell looked like, which in turn demanded a revolution in how we understood the wretchedness of life, the fate of the sinful, and the path out through an all too earthly call to love and poetry. How human beings behave is, for fairly evident reasons, a topic of intense interest to human beings. And yet, not only is there much we don’t understand about human behavior, different academic disciplines seem to have developed completely incompatible models to try to explain it. And as today’s guest Herb Gintis complains, they don’t put nearly enough effort into talking to each other to try to reconcile their views. So that what he’s here to do. Using game theory and a model of rational behavior — with an expanded notion of “rationality” that includes social as well as personally selfish interests — he thinks that we can come to an understanding that includes ideas from biology, economics, psychology, and sociology, to more accurately account for how people actually behave.

How human beings behave is, for fairly evident reasons, a topic of intense interest to human beings. And yet, not only is there much we don’t understand about human behavior, different academic disciplines seem to have developed completely incompatible models to try to explain it. And as today’s guest Herb Gintis complains, they don’t put nearly enough effort into talking to each other to try to reconcile their views. So that what he’s here to do. Using game theory and a model of rational behavior — with an expanded notion of “rationality” that includes social as well as personally selfish interests — he thinks that we can come to an understanding that includes ideas from biology, economics, psychology, and sociology, to more accurately account for how people actually behave. Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) was the foremost anthropologist of the twentieth century, and one of its most renowned intellectuals of any persuasion. Common readers, if they know him at all, tend to do so only by Tristes Tropiques (French for “Sad Tropics”), his 1955 memoir of his fieldwork among Brazilian tribes and his travels as an academic junketeer in other alien enclaves. That book is salted with animadversions on the spread of the “monoculture” of the West doing its worst to refashion the world in its unhandsome image.

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) was the foremost anthropologist of the twentieth century, and one of its most renowned intellectuals of any persuasion. Common readers, if they know him at all, tend to do so only by Tristes Tropiques (French for “Sad Tropics”), his 1955 memoir of his fieldwork among Brazilian tribes and his travels as an academic junketeer in other alien enclaves. That book is salted with animadversions on the spread of the “monoculture” of the West doing its worst to refashion the world in its unhandsome image. The day I was diagnosed with cancer—serious cancer, out-of-the-blue cancer—I reeled out of the doctor’s office and onto the familiar street. My children’s dentist was on that block, and the Rite Aid where we got cheap toys after their checkups. Just an hour and a half earlier, I’d walked down that street and my world had been safe and whole—my two little boys, my good husband, my career as a writer just beginning to unfold. My life! I hadn’t even known to give it a backward glance.

The day I was diagnosed with cancer—serious cancer, out-of-the-blue cancer—I reeled out of the doctor’s office and onto the familiar street. My children’s dentist was on that block, and the Rite Aid where we got cheap toys after their checkups. Just an hour and a half earlier, I’d walked down that street and my world had been safe and whole—my two little boys, my good husband, my career as a writer just beginning to unfold. My life! I hadn’t even known to give it a backward glance. In 1789, newly elected president

In 1789, newly elected president  “Climate change may be too wild a stream to be navigated in the accustomed barques of narration, yet we have entered a time in human history when the wild has become the norm,” writes Amitav Ghosh in his book The Great Derangement, and part of the reason Anna and I chose more lyric modes of documentation for this project was the impossibility of a linear narrative, of straightforward representation. How could we present something that’s long-term and large-scale dramatic, but harder to see in smaller daily moments, and almost impossible to photograph: raised roads in Miami Beach leaving sidewalks and storefronts below grade, or giant pumps that move water from the streets back into the Bay that simply look like large metal boxes? What language should we use to describe the paradox of a city in a time of sea-level rise, lying just feet above sea level, that’s also built on porous limestone—where rampant development means that multimillion-dollar waterfront houses and condominiums are still going up all along the shoreline?

“Climate change may be too wild a stream to be navigated in the accustomed barques of narration, yet we have entered a time in human history when the wild has become the norm,” writes Amitav Ghosh in his book The Great Derangement, and part of the reason Anna and I chose more lyric modes of documentation for this project was the impossibility of a linear narrative, of straightforward representation. How could we present something that’s long-term and large-scale dramatic, but harder to see in smaller daily moments, and almost impossible to photograph: raised roads in Miami Beach leaving sidewalks and storefronts below grade, or giant pumps that move water from the streets back into the Bay that simply look like large metal boxes? What language should we use to describe the paradox of a city in a time of sea-level rise, lying just feet above sea level, that’s also built on porous limestone—where rampant development means that multimillion-dollar waterfront houses and condominiums are still going up all along the shoreline?