Justin Taylor at Bookforum:

That something can be existent without properly existing, caught halfway between being and nonbeing, or between life and death, is a concept much larger than Williams’s straightforward claims about the eradication of the Everglades. The notion of a foundational in-between-ness, of existence itself as a fleeting or fugacious form, has been central to her work from the very beginning. The writer Vincent Scarpa, who has studied and taught Williams’s work extensively, put it to me this way: “That liminal state between being alive and being dead—that’s Joy’s playground.” He reminded me that nursing homes, “these collectives where it goes unacknowledged or otherwise refused that the living are only playing at living,” feature frequently in her work. “But we’re really all in that liminal state, just to varying degrees.” Sure enough, a nursing home is a central setting of Williams’s novel The Quick and the Dead (2000), which also features a petulant ghost. Expand the category a bit and you’ll find hospitals and hotels along with rest homes. Her 1988 novel, Breaking and Entering, is about a pair of drifters who squat Florida vacation homes. Florida itself is sometimes known as “God’s Waiting Room.”

That something can be existent without properly existing, caught halfway between being and nonbeing, or between life and death, is a concept much larger than Williams’s straightforward claims about the eradication of the Everglades. The notion of a foundational in-between-ness, of existence itself as a fleeting or fugacious form, has been central to her work from the very beginning. The writer Vincent Scarpa, who has studied and taught Williams’s work extensively, put it to me this way: “That liminal state between being alive and being dead—that’s Joy’s playground.” He reminded me that nursing homes, “these collectives where it goes unacknowledged or otherwise refused that the living are only playing at living,” feature frequently in her work. “But we’re really all in that liminal state, just to varying degrees.” Sure enough, a nursing home is a central setting of Williams’s novel The Quick and the Dead (2000), which also features a petulant ghost. Expand the category a bit and you’ll find hospitals and hotels along with rest homes. Her 1988 novel, Breaking and Entering, is about a pair of drifters who squat Florida vacation homes. Florida itself is sometimes known as “God’s Waiting Room.”

more here.

Half a decade on, “Brexit and Trump” remain shorthand for the rise of right-wing populism and a profound unsettling of liberal democracies. One curious fact is rarely mentioned: the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Remain in 2016 had similar-sounding slogans, which spectacularly failed to resonate with large parts of the electorate: “Stronger Together” and “Stronger in Europe”. Evidently, a significant number of citizens felt that they might actually be stronger, or in some other sense better off, by separating. What does that tell us about the fault lines of politics today?

Half a decade on, “Brexit and Trump” remain shorthand for the rise of right-wing populism and a profound unsettling of liberal democracies. One curious fact is rarely mentioned: the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Remain in 2016 had similar-sounding slogans, which spectacularly failed to resonate with large parts of the electorate: “Stronger Together” and “Stronger in Europe”. Evidently, a significant number of citizens felt that they might actually be stronger, or in some other sense better off, by separating. What does that tell us about the fault lines of politics today? Our mushy brains seem a far cry from the solid silicon chips in computer processors, but scientists have a long history of comparing the two. As Alan Turing

Our mushy brains seem a far cry from the solid silicon chips in computer processors, but scientists have a long history of comparing the two. As Alan Turing  A little over half a century ago, in 1970, my mother’s parents took her to Kabul to shop for her wedding. From Lahore, Kabul was only a short flight or a long drive away, much closer than Karachi. It was the first time my mother had left Pakistan.

A little over half a century ago, in 1970, my mother’s parents took her to Kabul to shop for her wedding. From Lahore, Kabul was only a short flight or a long drive away, much closer than Karachi. It was the first time my mother had left Pakistan. A

A The title of this book is a surprise. Chesterton’s admirers have regarded him as a saintly figure; indeed he has been proposed for canonisation. Even those, like Bernard Shaw and H G Wells, who engaged in fierce argument with him regarded him with affection. He was a master of paradox whose sincerity was nevertheless rarely questioned. Orwell’s complaint that everything Chesterton wrote was intended to demonstrate the superiority of the Catholic Church was nonsense, and not only because he didn’t convert until 1922, when he was forty-eight, by which time he had, as Richard Ingrams observes, written his best books. It would be truer, though still an exaggeration, to say that everything he wrote was intended to demonstrate the good sense of the ordinary man. He might well, like a certain Tory politician today, have said we have had enough of experts.

The title of this book is a surprise. Chesterton’s admirers have regarded him as a saintly figure; indeed he has been proposed for canonisation. Even those, like Bernard Shaw and H G Wells, who engaged in fierce argument with him regarded him with affection. He was a master of paradox whose sincerity was nevertheless rarely questioned. Orwell’s complaint that everything Chesterton wrote was intended to demonstrate the superiority of the Catholic Church was nonsense, and not only because he didn’t convert until 1922, when he was forty-eight, by which time he had, as Richard Ingrams observes, written his best books. It would be truer, though still an exaggeration, to say that everything he wrote was intended to demonstrate the good sense of the ordinary man. He might well, like a certain Tory politician today, have said we have had enough of experts.

Five years ago, French navy officer Jérôme Chardon was listening to a radio program about the extraordinary journey of the bar-tailed godwit, a bird that migrates 14,000 kilometers between New Zealand and Alaska. In his job as the coordinator of rescue operations across Southeast Asia and French Polynesia, Chardon understood better than most how treacherous the journey would be, as ferocious storms frequently disrupt Pacific island communities. Yet, somehow, bar-tailed godwits routinely pass through the area unscathed. Chardon wondered whether learning how godwits navigate could help coastal communities avoid disaster. Could tracking birds help save lives?

Five years ago, French navy officer Jérôme Chardon was listening to a radio program about the extraordinary journey of the bar-tailed godwit, a bird that migrates 14,000 kilometers between New Zealand and Alaska. In his job as the coordinator of rescue operations across Southeast Asia and French Polynesia, Chardon understood better than most how treacherous the journey would be, as ferocious storms frequently disrupt Pacific island communities. Yet, somehow, bar-tailed godwits routinely pass through the area unscathed. Chardon wondered whether learning how godwits navigate could help coastal communities avoid disaster. Could tracking birds help save lives? February 14, 1989, and September 11, 2001, have stood like bookends in my occasional writing on contemporary politics as it relates to Muslims. A rite of passage, a personal education. But the personal here reflects something wider in American, more generally Western, public life.

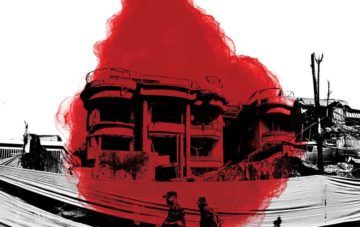

February 14, 1989, and September 11, 2001, have stood like bookends in my occasional writing on contemporary politics as it relates to Muslims. A rite of passage, a personal education. But the personal here reflects something wider in American, more generally Western, public life. The Taliban observed the 20th anniversary of 9/11 in startling fashion. Within a week of the United States’ announcement that it would withdraw its forces from Afghanistan on September 11, the Taliban had taken over large parts of the country, and on August 15, the capital city of Kabul fell. The speed was astonishing, the strategic acumen remarkable: a 20-year occupation rolled up in a week, as the puppet armies disintegrated. The puppet president hopped a helicopter to Uzbekistan, then a jet to the United Arab Emirates. It was a huge blow to the American empire and its underling states. No amount of spin can cover up this debacle.

The Taliban observed the 20th anniversary of 9/11 in startling fashion. Within a week of the United States’ announcement that it would withdraw its forces from Afghanistan on September 11, the Taliban had taken over large parts of the country, and on August 15, the capital city of Kabul fell. The speed was astonishing, the strategic acumen remarkable: a 20-year occupation rolled up in a week, as the puppet armies disintegrated. The puppet president hopped a helicopter to Uzbekistan, then a jet to the United Arab Emirates. It was a huge blow to the American empire and its underling states. No amount of spin can cover up this debacle. What 9/11 illustrates is that terrorism is about psychology, not damage. Terrorism is like theatre. With their powerful military, Americans believe that “shock and awe” comes from massive bombardment. For terrorists, shock and awe comes from the drama more than the number of deaths caused by their attacks. Poisons might kill more people, but explosions get the visuals. The constant replay of the falling Twin Towers on the world’s television sets was Osama bin Laden’s coup.

What 9/11 illustrates is that terrorism is about psychology, not damage. Terrorism is like theatre. With their powerful military, Americans believe that “shock and awe” comes from massive bombardment. For terrorists, shock and awe comes from the drama more than the number of deaths caused by their attacks. Poisons might kill more people, but explosions get the visuals. The constant replay of the falling Twin Towers on the world’s television sets was Osama bin Laden’s coup. How much attention should each of us be paying to our individual carbon footprint? That question is the subject of a contentious debate that’s been raging in climate circles for quite some time.

How much attention should each of us be paying to our individual carbon footprint? That question is the subject of a contentious debate that’s been raging in climate circles for quite some time. When workers do not come into a city, a city can wither; and an examination of

When workers do not come into a city, a city can wither; and an examination of

S

S