Gili Kliger in Public Books:

When the philosopher Amia Srinivasan’s essay “The Right to Sex” appeared in the London Review of Books, in 2018, it garnered a level of attention not usually paid to writing by academics. From the provocative title to the bracing clarity of the content (“Sex is not a sandwich,” Srinivasan wrote), the essay’s stylistic appeal was matched by a willingness to entertain positions that had long been off the table in both feminist and mainstream discussions of sex. The piece responded to the commentary surrounding Elliot Rodger, perhaps the most famous of the so-called incels, or involuntary celibates, who in 2014 killed six people after penning a 107,000-word manifesto that railed against the women who had deprived him of sex. Many feminists were quick to read Rodger as a case study in male sexual entitlement. Fewer wanted to broach one of the manifesto’s thornier claims: that Rodger, who was half white and half Malaysian Chinese, had been denied sex because of his race. Srinivasan took Rodger’s undesirability head-on: of course, no one has a right to be desired, she wrote. But we ought to acknowledge, as second-wave feminists more readily did, that who or what is desired is a political question, subject to scrutiny.

When the philosopher Amia Srinivasan’s essay “The Right to Sex” appeared in the London Review of Books, in 2018, it garnered a level of attention not usually paid to writing by academics. From the provocative title to the bracing clarity of the content (“Sex is not a sandwich,” Srinivasan wrote), the essay’s stylistic appeal was matched by a willingness to entertain positions that had long been off the table in both feminist and mainstream discussions of sex. The piece responded to the commentary surrounding Elliot Rodger, perhaps the most famous of the so-called incels, or involuntary celibates, who in 2014 killed six people after penning a 107,000-word manifesto that railed against the women who had deprived him of sex. Many feminists were quick to read Rodger as a case study in male sexual entitlement. Fewer wanted to broach one of the manifesto’s thornier claims: that Rodger, who was half white and half Malaysian Chinese, had been denied sex because of his race. Srinivasan took Rodger’s undesirability head-on: of course, no one has a right to be desired, she wrote. But we ought to acknowledge, as second-wave feminists more readily did, that who or what is desired is a political question, subject to scrutiny.

In her debut collection of essays, The Right to Sex: Feminism in the Twenty-First Century, out this month, Srinivasan extends on the LRB piece by bringing analytic precision to a range of related subjects: Title IX and consent, the ethics of professor-student relationships, the role of pornography in shaping sexual expectations and desires, and the criminalization of sex work.

More here.

As spring ends, maple trees begin to unfetter winged seeds that flutter and swirl from branches to land gently on the ground. Inspired by the aerodynamics of these helicoptering pods, as well as other

As spring ends, maple trees begin to unfetter winged seeds that flutter and swirl from branches to land gently on the ground. Inspired by the aerodynamics of these helicoptering pods, as well as other  During her lifetime, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61) was widely regarded as Britain’s best female poet. Her groundbreaking work helped sway public opinion against slavery and child labor and changed the direction of English-language poetry for generations. Yet within 70 years of her death, Barrett Browning was no longer viewed as an international literary superstar but as an invalid with a small, couch-bound life. By the 1970s, critics described her as lacking the talent of her husband, Robert Browning, and hindering his writing. Fiona Sampson challenges those views in “Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,” the first new biography of the poet in more than 30 years. Sampson, whose works include the critically acclaimed biography “In Search of Mary Shelley,” reframes Barrett Browning’s reputation by highlighting her development as a writer despite the many restrictions she faced in Victorian society.

During her lifetime, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61) was widely regarded as Britain’s best female poet. Her groundbreaking work helped sway public opinion against slavery and child labor and changed the direction of English-language poetry for generations. Yet within 70 years of her death, Barrett Browning was no longer viewed as an international literary superstar but as an invalid with a small, couch-bound life. By the 1970s, critics described her as lacking the talent of her husband, Robert Browning, and hindering his writing. Fiona Sampson challenges those views in “Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,” the first new biography of the poet in more than 30 years. Sampson, whose works include the critically acclaimed biography “In Search of Mary Shelley,” reframes Barrett Browning’s reputation by highlighting her development as a writer despite the many restrictions she faced in Victorian society. How should we think of human rationality? The cognitive wherewithal to understand the world and bend it to our advantage is not a trophy of Western civilization; it’s the patrimony of our species. The San of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa are one of the world’s oldest peoples, and their foraging lifestyle, maintained until recently, offers a glimpse of the ways in which humans spent most of their existence. Hunter-gatherers don’t just chuck spears at passing animals or help themselves to fruit and nuts growing around them. The tracking scientist Louis Liebenberg, who has worked with the San for decades, has described how they owe their survival to a scientific mindset. They reason their way from fragmentary data to remote conclusions with an intuitive grasp of logic, critical thinking, statistical reasoning, correlation and causation, and game theory.

How should we think of human rationality? The cognitive wherewithal to understand the world and bend it to our advantage is not a trophy of Western civilization; it’s the patrimony of our species. The San of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa are one of the world’s oldest peoples, and their foraging lifestyle, maintained until recently, offers a glimpse of the ways in which humans spent most of their existence. Hunter-gatherers don’t just chuck spears at passing animals or help themselves to fruit and nuts growing around them. The tracking scientist Louis Liebenberg, who has worked with the San for decades, has described how they owe their survival to a scientific mindset. They reason their way from fragmentary data to remote conclusions with an intuitive grasp of logic, critical thinking, statistical reasoning, correlation and causation, and game theory. Servaas Storm over at INET:

Servaas Storm over at INET: Becca Rothfield in Boston Review:

Becca Rothfield in Boston Review: Adam Tooze at his podcast Ones and Tooze over at Foreign Policy:

Adam Tooze at his podcast Ones and Tooze over at Foreign Policy: Marco D’Eramo in NLR’s Sidecar (Photo by

Marco D’Eramo in NLR’s Sidecar (Photo by  In December 1915, while serving on the Russian front, the German astronomer and mathematician Karl Schwarzschild sent a letter to Albert Einstein that contained the first precise solution to the equations of general relativity. Schwarzschild’s approach had been simple. He had plugged Einstein’s equations into a model that posited an ideal, perfectly spherical star, in order to calculate how its mass would warp the surrounding space. Schwarzschild’s solution was elegant, but it revealed something monstrous: If the same process were applied not to an ideal star but to one that had begun to collapse, its density and gravity would increase infinitely, creating an enclosed region of space-time, or a singularity, from which nothing could escape. Schwarzschild had given the world its first glimpse of black holes.

In December 1915, while serving on the Russian front, the German astronomer and mathematician Karl Schwarzschild sent a letter to Albert Einstein that contained the first precise solution to the equations of general relativity. Schwarzschild’s approach had been simple. He had plugged Einstein’s equations into a model that posited an ideal, perfectly spherical star, in order to calculate how its mass would warp the surrounding space. Schwarzschild’s solution was elegant, but it revealed something monstrous: If the same process were applied not to an ideal star but to one that had begun to collapse, its density and gravity would increase infinitely, creating an enclosed region of space-time, or a singularity, from which nothing could escape. Schwarzschild had given the world its first glimpse of black holes. The

The  Wole Soyinka the firebrand activist is always getting Wole Soyinka the writer into trouble.

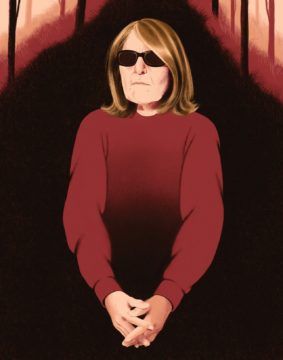

Wole Soyinka the firebrand activist is always getting Wole Soyinka the writer into trouble. You don’t encounter the fiction of Joy Williams without experiencing a measure of bewilderment. Williams, one of the country’s best living writers of the short story, draws praise from titans such as George Saunders, Don DeLillo, and Lauren Groff, and many of her readers, having imprinted on her wayward phrasing and screwball characters, will follow her anywhere. But the route can be disorienting, like climbing an uneven staircase in a dream. Her tales offer a dark, provisional illumination, and they make the kind of sense that disperses upon waking. For years, Williams has worn sunglasses at all hours, as if to blacken her vision. The central subject of art, she has written, is “nothingness.”

You don’t encounter the fiction of Joy Williams without experiencing a measure of bewilderment. Williams, one of the country’s best living writers of the short story, draws praise from titans such as George Saunders, Don DeLillo, and Lauren Groff, and many of her readers, having imprinted on her wayward phrasing and screwball characters, will follow her anywhere. But the route can be disorienting, like climbing an uneven staircase in a dream. Her tales offer a dark, provisional illumination, and they make the kind of sense that disperses upon waking. For years, Williams has worn sunglasses at all hours, as if to blacken her vision. The central subject of art, she has written, is “nothingness.”

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times. Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize during his first year in the White House, but he also became the first U.S. president to be at war during the entirety of his two terms in office. The irony of this contrast has often been noted. To historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn, it represents more than a case of poor judgment by the Nobel committee—or, as others might see it, an example of how the toxic politics surrounding terrorism can blunt the best of intentions.

Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize during his first year in the White House, but he also became the first U.S. president to be at war during the entirety of his two terms in office. The irony of this contrast has often been noted. To historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn, it represents more than a case of poor judgment by the Nobel committee—or, as others might see it, an example of how the toxic politics surrounding terrorism can blunt the best of intentions.