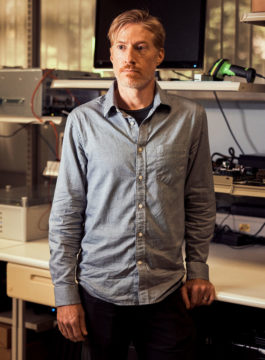

Robert Service in Science:

HILLSBORO, OREGON—Though he catches flak for it, Garrett Kenyon, a physicist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, calls artificial intelligence (AI) “overhyped.” The algorithms that underlie everything from Alexa’s voice recognition to credit card fraud detection typically owe their skills to deep learning, in which the software learns to perform specific tasks by churning through vast databases of examples. These programs, Kenyon points out, don’t organize and process information the way human brains do, and they fall short when it comes to the versatile smarts needed for fully autonomous robots, for example. “We have a lot of fabulous devices out there that are incredibly useful,” Kenyon says. “But I would not call any of that particularly intelligent.”

Kenyon and many others see hope for smarter computers in an upstart technology called neuromorphic computing. In place of standard computing architecture, which processes information linearly, neuromorphic chips emulate the way our brains process information, with myriad digital neurons working in parallel to send electrical impulses, or spikes, to networks of other neurons. Each silicon neuron fires when it receives enough spikes, passing along its excitation to other neurons, and the system learns by reinforcing connections that fire regularly while paring away those that don’t. The approach excels at spotting patterns in large amounts of noisy data, which can speed learning. Because information processing takes place throughout the network of neurons, neuromorphic chips also require far less shuttling of data between memory and processing circuits, boosting speed and energy efficiency.

Neuromorphic computing isn’t new. Yet, progress has been slow, with chipmakers reluctant to invest in the technology without a proven market, and algorithm developers struggling to write software for an entirely new computer architecture. But the field appears to be maturing as the capabilities of the chips increase, which has attracted a growing community of software developers.

More here.

The control of infectious disease is one of the unambiguously great accomplishments of our species. Through a succession of overlapping and mutually reinforcing innovations at several scales—from public health reforms and the so-called hygiene revolution, to chemical controls and biomedical interventions like antibiotics, vaccines, and improvements to patient care—humans have learned to make the environments we inhabit unfit for microbes that cause us harm. This transformation has prevented immeasurable bodily pain and allowed billions of humans the chance to reach their full potential. It has relieved countless parents from the anguish of burying their children. It has remade our basic assumptions about life and death. Scholars have found plenty of candidates for what made us “modern” (railroads, telephones, science, Shakespeare), but the control of our microbial adversaries is as compelling as any of them. The mastery of microbes is so elemental and so intimately bound up with the other features of modernity—economic growth, mass education, the empowerment of women—that it is hard to imagine a counterfactual path to the modern world in which we lack a basic level of control over our germs. Modernity and pestilence are mutually exclusive; the COVID-19 pandemic only underscores their incompatibility.

The control of infectious disease is one of the unambiguously great accomplishments of our species. Through a succession of overlapping and mutually reinforcing innovations at several scales—from public health reforms and the so-called hygiene revolution, to chemical controls and biomedical interventions like antibiotics, vaccines, and improvements to patient care—humans have learned to make the environments we inhabit unfit for microbes that cause us harm. This transformation has prevented immeasurable bodily pain and allowed billions of humans the chance to reach their full potential. It has relieved countless parents from the anguish of burying their children. It has remade our basic assumptions about life and death. Scholars have found plenty of candidates for what made us “modern” (railroads, telephones, science, Shakespeare), but the control of our microbial adversaries is as compelling as any of them. The mastery of microbes is so elemental and so intimately bound up with the other features of modernity—economic growth, mass education, the empowerment of women—that it is hard to imagine a counterfactual path to the modern world in which we lack a basic level of control over our germs. Modernity and pestilence are mutually exclusive; the COVID-19 pandemic only underscores their incompatibility. Traditional physics works within the “Laplacian paradigm”: you give me the state of the universe (or some closed system), some equations of motion, then I use those equations to evolve the system through time.

Traditional physics works within the “Laplacian paradigm”: you give me the state of the universe (or some closed system), some equations of motion, then I use those equations to evolve the system through time.  I gave my first lecture, at my first academic job, behind a wall of plexiglass, speaking to an awkwardly spaced out group of masked students who had maybe already given up – and honestly, who could blame them? I walked in sweating and late because my building’s social distancing protocol required me to run up five floors and down two to get to my third floor classroom. Leaning into the mic, I opened with the joke: “Welcome to apocalyptic poetry!”

I gave my first lecture, at my first academic job, behind a wall of plexiglass, speaking to an awkwardly spaced out group of masked students who had maybe already given up – and honestly, who could blame them? I walked in sweating and late because my building’s social distancing protocol required me to run up five floors and down two to get to my third floor classroom. Leaning into the mic, I opened with the joke: “Welcome to apocalyptic poetry!” It’s 2036, and you have kidney failure. Until recently, this condition meant months or years of gruelling dialysis, while you hoped that a suitable donor would emerge to provide you with replacement kidneys. Today, thanks to a new technology, you’re going to grow your own. A technician collects a small sample of your blood or skin and takes it to a laboratory. There, the cells it contains are separated out, cultured and treated with various drugs. The procedure transforms the cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which, like the cells of an early embryo, are capable of generating any of the body’s tissues. Next, the technician selects a pig embryo that has been engineered to lack a gene required to grow kidneys, and injects your iPS cells into it. This embryo is implanted in a surrogate sow, where it develops into a young pig that has two kidneys consisting of your human cells. Eventually, these kidneys are transplanted into your body, massively extending your life expectancy.

It’s 2036, and you have kidney failure. Until recently, this condition meant months or years of gruelling dialysis, while you hoped that a suitable donor would emerge to provide you with replacement kidneys. Today, thanks to a new technology, you’re going to grow your own. A technician collects a small sample of your blood or skin and takes it to a laboratory. There, the cells it contains are separated out, cultured and treated with various drugs. The procedure transforms the cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which, like the cells of an early embryo, are capable of generating any of the body’s tissues. Next, the technician selects a pig embryo that has been engineered to lack a gene required to grow kidneys, and injects your iPS cells into it. This embryo is implanted in a surrogate sow, where it develops into a young pig that has two kidneys consisting of your human cells. Eventually, these kidneys are transplanted into your body, massively extending your life expectancy. The curse of genre is that it encourages filmmakers to downplay causes in the interest of effects. In the best genre movies, the quantity and power of these effects serve as sufficient compensation for the thinned-out drama. “Titane,” the new film by Julia Ducournau, is a genre film, a twist on horror with a twist on family—like Ducournau’s first feature, “Raw.” But “Titane” is far stronger, far wilder, far stranger. The radical fantasy of its premise—a woman gets impregnated by a car—wrenches the ensuing family drama out of the realm of the ordinary and into one of speculative fantasy and imaginative wonder that demands a suspension of disbelief—which becomes the movie’s very subject.

The curse of genre is that it encourages filmmakers to downplay causes in the interest of effects. In the best genre movies, the quantity and power of these effects serve as sufficient compensation for the thinned-out drama. “Titane,” the new film by Julia Ducournau, is a genre film, a twist on horror with a twist on family—like Ducournau’s first feature, “Raw.” But “Titane” is far stronger, far wilder, far stranger. The radical fantasy of its premise—a woman gets impregnated by a car—wrenches the ensuing family drama out of the realm of the ordinary and into one of speculative fantasy and imaginative wonder that demands a suspension of disbelief—which becomes the movie’s very subject. BLVR: It’s interesting that you make the distinction between art and not-art, because your writing doesn’t seem to make that distinction.

BLVR: It’s interesting that you make the distinction between art and not-art, because your writing doesn’t seem to make that distinction. The fundamental struggle with water has never really abated since it first began on the shores of the Persian Gulf. The multiple transitions, from nomadism to sedentism, from hunting and foraging to domesticated agriculture, from small rural communities to a productive, specialized, urbanized society, were severe disruptions. But while individuals would have lived through them as gradual, incremental transformations, over the course of Homo sapiens’ existence, they amounted to shocking events. From the moment Homo sapiens, late in its history, decided to stay in one place, surrounded by a changing environment, it began to wrestle with water, an agent capable of destruction and life-giving gifts.

The fundamental struggle with water has never really abated since it first began on the shores of the Persian Gulf. The multiple transitions, from nomadism to sedentism, from hunting and foraging to domesticated agriculture, from small rural communities to a productive, specialized, urbanized society, were severe disruptions. But while individuals would have lived through them as gradual, incremental transformations, over the course of Homo sapiens’ existence, they amounted to shocking events. From the moment Homo sapiens, late in its history, decided to stay in one place, surrounded by a changing environment, it began to wrestle with water, an agent capable of destruction and life-giving gifts. T

T IN AN APPRECIATIVE 2016 REVIEW of new work by Valerie Jaudon, critic David Frankel noted that the Pattern and Decoration movement, of which Jaudon was a prominent member, had long been held in disrepute. “In the early ’80s,” Frankel wrote, “I remember a colleague at Artforum at the time saying it could never be taken seriously in the magazine.”1 In retrospect, what makes this dismissal so striking is that, in the mid-’70s, Artforum contributed significantly to P&D’s emergence into the spotlight, publishing key texts by its advocates along with numerous reviews of its shows. Amy Goldin’s “Patterns, Grids, and Painting” (1975) and Jeff Perrone’s “Approaching the Decorative” (1976) were among the early touchstones for P&D’s heterogeneous cohort, riled by the unmitigated critical support for diverse ascetic and masculinist tendencies pervasive in the painting of the moment. However, by the mid-’80s, eclipsed by newer developments—the Pictures generation, neo-geo, et al.—P&D was increasingly coming under fire for positions now considered controversial: for the purported essentialism of its versions of second-wave feminism, for a naive advocacy that masked acts of Orientalizing and primitivizing, for cultural imperialism. More fundamental “problems” largely went unnoted, including a lack of the kind of conceptual depth expected of cutting-edge practices: In their commitment to the decorative, P&D artists prioritized surface over subject matter, the former serving primarily as a vehicle for sensuous effects. Not least, the art world’s entrenched sexism fostered the occasion for its denizens to belittle and sideline a movement renowned for the dominant role played by women in its genesis and trajectory.

IN AN APPRECIATIVE 2016 REVIEW of new work by Valerie Jaudon, critic David Frankel noted that the Pattern and Decoration movement, of which Jaudon was a prominent member, had long been held in disrepute. “In the early ’80s,” Frankel wrote, “I remember a colleague at Artforum at the time saying it could never be taken seriously in the magazine.”1 In retrospect, what makes this dismissal so striking is that, in the mid-’70s, Artforum contributed significantly to P&D’s emergence into the spotlight, publishing key texts by its advocates along with numerous reviews of its shows. Amy Goldin’s “Patterns, Grids, and Painting” (1975) and Jeff Perrone’s “Approaching the Decorative” (1976) were among the early touchstones for P&D’s heterogeneous cohort, riled by the unmitigated critical support for diverse ascetic and masculinist tendencies pervasive in the painting of the moment. However, by the mid-’80s, eclipsed by newer developments—the Pictures generation, neo-geo, et al.—P&D was increasingly coming under fire for positions now considered controversial: for the purported essentialism of its versions of second-wave feminism, for a naive advocacy that masked acts of Orientalizing and primitivizing, for cultural imperialism. More fundamental “problems” largely went unnoted, including a lack of the kind of conceptual depth expected of cutting-edge practices: In their commitment to the decorative, P&D artists prioritized surface over subject matter, the former serving primarily as a vehicle for sensuous effects. Not least, the art world’s entrenched sexism fostered the occasion for its denizens to belittle and sideline a movement renowned for the dominant role played by women in its genesis and trajectory. Anil Seth

Anil Seth The first time I learned I was Muslim was in preschool.

The first time I learned I was Muslim was in preschool. COVID-19 deaths and cases are starting to decline and some

COVID-19 deaths and cases are starting to decline and some