David Remnick in The New Yorker:

Early evening in late summer, the golden hour in the village of East Hampton. The surf is rough and pounds its regular measure on the shore. At the last driveway on a road ending at the beach, a cortège of cars—S.U.V.s, jeeps, candy-colored roadsters—pull up to the gate, sand crunching pleasantly under the tires. And out they come, face after famous face, burnished, expensively moisturized: Jerry Seinfeld, Jimmy Buffett, Anjelica Huston, Julianne Moore, Stevie Van Zandt, Alec Baldwin, Jon Bon Jovi. They all wear expectant, delighted-to-be-invited expressions. Through the gate, they mount a flight of stairs to the front door and walk across a vaulted living room to a fragrant back yard, where a crowd is circulating under a tent in the familiar high-life way, regarding the territory, pausing now and then to accept refreshments from a tray.

Early evening in late summer, the golden hour in the village of East Hampton. The surf is rough and pounds its regular measure on the shore. At the last driveway on a road ending at the beach, a cortège of cars—S.U.V.s, jeeps, candy-colored roadsters—pull up to the gate, sand crunching pleasantly under the tires. And out they come, face after famous face, burnished, expensively moisturized: Jerry Seinfeld, Jimmy Buffett, Anjelica Huston, Julianne Moore, Stevie Van Zandt, Alec Baldwin, Jon Bon Jovi. They all wear expectant, delighted-to-be-invited expressions. Through the gate, they mount a flight of stairs to the front door and walk across a vaulted living room to a fragrant back yard, where a crowd is circulating under a tent in the familiar high-life way, regarding the territory, pausing now and then to accept refreshments from a tray.

Their hosts are Nancy Shevell, the scion of a New Jersey trucking family, and her husband, Paul McCartney, a bass player and singer-songwriter from Liverpool. A slender, regal woman in her early sixties, Shevell is talking in a confiding manner with Michael Bloomberg, who was the mayor of New York City when she served on the board of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Bloomberg nods gravely at whatever Shevell is saying, but he has his eyes fixed on a plate of exquisite little pizzas. Would he like one? He narrows his gaze, trying to decide; then, with executive dispatch, he declines.

McCartney greets his guests with the same twinkly smile and thumbs-up charm that once led him to be called “the cute Beatle.” Even in a crowd of the accomplished and abundantly self-satisfied, he is invariably the focus of attention. His fan base is the general population. There are myriad ways in which people betray their pleasure in encountering him—describing their favorite songs, asking for selfies and autographs, or losing their composure entirely.

This effect extends to friends and peers. Billy Joel, who has sold out Madison Square Garden more than a hundred times, has spent Hamptons afternoons over the years with McCartney. Still, Joel told me, “he’s a Beatle, so there’s an intimidation factor. You encounter someone like Paul and you wonder how close you can be to someone like that.”

More here.

I

I  Renewable energy seems set to repeat many of the mistakes of fossil fuels. Though wind and solar power will not degrade the conditions for life on planet earth, the geography and corporate structure of these industries concentrate benefits and exclude communities in the style of Big Oil. The neighbors tend to notice—and to complain. So-called “

Renewable energy seems set to repeat many of the mistakes of fossil fuels. Though wind and solar power will not degrade the conditions for life on planet earth, the geography and corporate structure of these industries concentrate benefits and exclude communities in the style of Big Oil. The neighbors tend to notice—and to complain. So-called “ Those of us who think that that

Those of us who think that that  Curiosity is very closely related to one of my most highly prized traits, what Keats called “negative capability”… “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” There’s whiff of Romantic mysticism about this, for sure, but I see it primarily as openness to complexity, comfort with ambiguity, patience with not knowing. (If you’ve never read it, “

Curiosity is very closely related to one of my most highly prized traits, what Keats called “negative capability”… “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” There’s whiff of Romantic mysticism about this, for sure, but I see it primarily as openness to complexity, comfort with ambiguity, patience with not knowing. (If you’ve never read it, “

Cynthia Ozick’s surprisingly scalding and chaotic

Cynthia Ozick’s surprisingly scalding and chaotic  For many of us over the last year and more, our waking experience has, you might say, lost a bit of its variety. We spend more time with the same people, in our homes, and go to fewer places. Our stimuli these days, in other words, aren’t very stimulating. Too much day-to-day routine, too much familiarity, too much predictability. At the same time, our dreams have gotten more

For many of us over the last year and more, our waking experience has, you might say, lost a bit of its variety. We spend more time with the same people, in our homes, and go to fewer places. Our stimuli these days, in other words, aren’t very stimulating. Too much day-to-day routine, too much familiarity, too much predictability. At the same time, our dreams have gotten more  The works carry a metaphysical meaning, as well as a geographical one. With the skulls and antlers, bones and shells, O’Keeffe creates a secular iconography. For her, these subjects did not represent death but something vital and lasting. A bone found in the desert is like a shell found on the beach: both are forms defined by function, both are beautiful and enduring evidence of life. O’Keeffe’s images and juxtapositions are mysterious, but she wasn’t a member of the Surrealist movement, which deliberately juxtaposed objects without connections to one another. Her intention was quite different: these objects have a deep connection—one that we recognize on an intuitive level. “Pelvis with the Distance,” from 1943, shows a smooth, white bone, all curves and slopes and openings. It is suspended, high in the air, above a line of low, undulant blue hills. This physical juxtaposition—the celestial locus of the bone, the earth-hugging horizon below—creates a majestic sweep of space. O’Keeffe places the viewer aloft, level with the bone, high up in the empyrean. The supernatural height, the mystery, the hallucinatory beauty of the object—all combine to create a sense of the sublime.

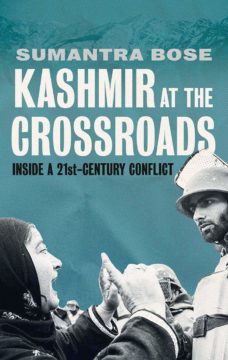

The works carry a metaphysical meaning, as well as a geographical one. With the skulls and antlers, bones and shells, O’Keeffe creates a secular iconography. For her, these subjects did not represent death but something vital and lasting. A bone found in the desert is like a shell found on the beach: both are forms defined by function, both are beautiful and enduring evidence of life. O’Keeffe’s images and juxtapositions are mysterious, but she wasn’t a member of the Surrealist movement, which deliberately juxtaposed objects without connections to one another. Her intention was quite different: these objects have a deep connection—one that we recognize on an intuitive level. “Pelvis with the Distance,” from 1943, shows a smooth, white bone, all curves and slopes and openings. It is suspended, high in the air, above a line of low, undulant blue hills. This physical juxtaposition—the celestial locus of the bone, the earth-hugging horizon below—creates a majestic sweep of space. O’Keeffe places the viewer aloft, level with the bone, high up in the empyrean. The supernatural height, the mystery, the hallucinatory beauty of the object—all combine to create a sense of the sublime. With admirable clarity, Sumantra Bose’s Kashmir at the Crossroads helps to explain the tensions and the motives of the various parties involved in the intractable Kashmir conflict, including Chinese cartographers, Indian Hindu nationalists, Pakistani intelligence officers, violent jihadists and the group that barely gets a look in, the Kashmiris themselves. Landlocked and surrounded by three antagonistic nuclear powers with claims on their land, the Kashmiris are always the last ones to have a say over their own future.

With admirable clarity, Sumantra Bose’s Kashmir at the Crossroads helps to explain the tensions and the motives of the various parties involved in the intractable Kashmir conflict, including Chinese cartographers, Indian Hindu nationalists, Pakistani intelligence officers, violent jihadists and the group that barely gets a look in, the Kashmiris themselves. Landlocked and surrounded by three antagonistic nuclear powers with claims on their land, the Kashmiris are always the last ones to have a say over their own future. A young musician attends the conservatory, a young artist studies at the academy, but the young writer has nowhere to go. You view this as an injustice. Not so. Schools for musicians and painters provide first and foremost technical knowledge you’d be hard pressed to acquire on your own in relatively short order. What is the writer to learn at his institute? Any ordinary school is all it takes to push a pen across the page. Literature holds no technical secrets, or at least secrets that can’t be plumbed by a gifted amateur (since no diploma will help the talentless). It’s the least professional of all artistic callings. You may take up writing at twenty or seventy. You may be a professor or an autodidact. You may skip your high school diploma (like Thomas Mann) or receive honorary doctorates at multiple universities (again like Mann). The road to Parnassus is open to all. In principle at least, since genes have the final say.

A young musician attends the conservatory, a young artist studies at the academy, but the young writer has nowhere to go. You view this as an injustice. Not so. Schools for musicians and painters provide first and foremost technical knowledge you’d be hard pressed to acquire on your own in relatively short order. What is the writer to learn at his institute? Any ordinary school is all it takes to push a pen across the page. Literature holds no technical secrets, or at least secrets that can’t be plumbed by a gifted amateur (since no diploma will help the talentless). It’s the least professional of all artistic callings. You may take up writing at twenty or seventy. You may be a professor or an autodidact. You may skip your high school diploma (like Thomas Mann) or receive honorary doctorates at multiple universities (again like Mann). The road to Parnassus is open to all. In principle at least, since genes have the final say.

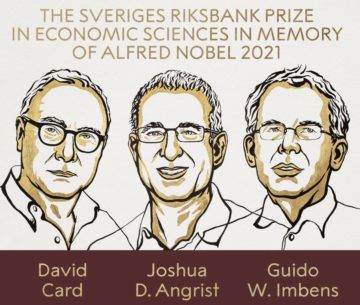

The Nobel Prize goes to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. If you seek their monuments look around you. Almost all of the empirical work in economics that you read in the popular press (and plenty that doesn’t make the popular press) is due to analyzing natural experiments using techniques such as difference in differences, instrumental variables and regression discontinuity. The techniques are powerful but the ideas behind them are also understandable by the person in the street which has given economists a tremendous advantage when talking with the public. Take, for example, the famous minimum wage study of

The Nobel Prize goes to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. If you seek their monuments look around you. Almost all of the empirical work in economics that you read in the popular press (and plenty that doesn’t make the popular press) is due to analyzing natural experiments using techniques such as difference in differences, instrumental variables and regression discontinuity. The techniques are powerful but the ideas behind them are also understandable by the person in the street which has given economists a tremendous advantage when talking with the public. Take, for example, the famous minimum wage study of  Early evening in late summer, the golden hour in the village of East Hampton. The surf is rough and pounds its regular measure on the shore. At the last driveway on a road ending at the beach, a cortège of cars—S.U.V.s, jeeps, candy-colored roadsters—pull up to the gate, sand crunching pleasantly under the tires. And out they come, face after famous face, burnished, expensively moisturized: Jerry Seinfeld, Jimmy Buffett, Anjelica Huston, Julianne Moore, Stevie Van Zandt, Alec Baldwin, Jon Bon Jovi. They all wear expectant, delighted-to-be-invited expressions. Through the gate, they mount a flight of stairs to the front door and walk across a vaulted living room to a fragrant back yard, where a crowd is circulating under a tent in the familiar high-life way, regarding the territory, pausing now and then to accept refreshments from a tray.

Early evening in late summer, the golden hour in the village of East Hampton. The surf is rough and pounds its regular measure on the shore. At the last driveway on a road ending at the beach, a cortège of cars—S.U.V.s, jeeps, candy-colored roadsters—pull up to the gate, sand crunching pleasantly under the tires. And out they come, face after famous face, burnished, expensively moisturized: Jerry Seinfeld, Jimmy Buffett, Anjelica Huston, Julianne Moore, Stevie Van Zandt, Alec Baldwin, Jon Bon Jovi. They all wear expectant, delighted-to-be-invited expressions. Through the gate, they mount a flight of stairs to the front door and walk across a vaulted living room to a fragrant back yard, where a crowd is circulating under a tent in the familiar high-life way, regarding the territory, pausing now and then to accept refreshments from a tray. Researchers at the DZNE and the University Medical Center Göttingen (UMG) have identified molecules in the blood that can indicate impending dementia. Their findings, which are presented in the scientific journal EMBO Molecular Medicine, are based on human studies and laboratory experiments. University hospitals across Germany were also involved in the investigations. The biomarker described by the team led by Prof. André Fischer is based on measuring levels of so-called microRNAs. The technique is not yet suitable for practical use; the scientists therefore aim to develop a simple blood test that can be applied in routine medical care to assess dementia risk. According to the study data, microRNAs could potentially also be targets for dementia therapy.

Researchers at the DZNE and the University Medical Center Göttingen (UMG) have identified molecules in the blood that can indicate impending dementia. Their findings, which are presented in the scientific journal EMBO Molecular Medicine, are based on human studies and laboratory experiments. University hospitals across Germany were also involved in the investigations. The biomarker described by the team led by Prof. André Fischer is based on measuring levels of so-called microRNAs. The technique is not yet suitable for practical use; the scientists therefore aim to develop a simple blood test that can be applied in routine medical care to assess dementia risk. According to the study data, microRNAs could potentially also be targets for dementia therapy.