Perri Klass in Smithsonian:

Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies.

Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies.

In 1821, a French physician, Pierre Bretonneau, gave the disease a name: diphtérite. He based it on the Greek word diphthera, for leather—a reference to the affliction’s signature physical feature, a thick, leathery buildup of dead tissue in a patient’s throat, which makes breathing and swallowing difficult, or impossible. And children, with their relatively small airways, were particularly vulnerable.

…Then, toward the end of the 19th century, scientists started identifying the bacteria that caused this human misery—giving the pathogen a name and delineating its poisonous weapon. It was diphtheria that led researchers around the world to unite in an unprecedented effort, using laboratory investigations to come up with new treatments for struggling, suffocating victims. And it was diphtheria that prompted doctors and public health officials to coordinate their efforts in cities worldwide, taking much of the terror out of a deadly disease.

More here.

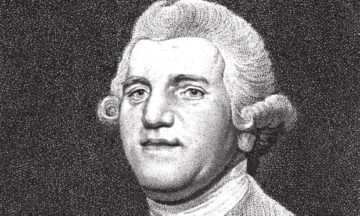

There are designers and there are designers. There are those who create beautiful objects and invent new techniques, some who transform taste, some who make a good business out of what may or may not be great products, some whose greatest talents are in selling. Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95) was all of the above, and more.

There are designers and there are designers. There are those who create beautiful objects and invent new techniques, some who transform taste, some who make a good business out of what may or may not be great products, some whose greatest talents are in selling. Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95) was all of the above, and more.

“Cloud Cuckoo Land,” a follow-up to Doerr’s best-selling novel “All the Light We Cannot See,” is, among other things, a paean to the nameless people who have played a role in the transmission of ancient texts and preserved the tales they tell. But it’s also about the consolations of stories and the balm they have provided for millenniums. It’s a wildly inventive novel that teems with life, straddles an enormous range of experience and learning, and embodies the storytelling gifts that it celebrates. It also pulls off a resolution that feels both surprising and inevitable, and that compels you back to the opening of the book with a head-shake of admiration at the Swiss-watchery of its construction.

“Cloud Cuckoo Land,” a follow-up to Doerr’s best-selling novel “All the Light We Cannot See,” is, among other things, a paean to the nameless people who have played a role in the transmission of ancient texts and preserved the tales they tell. But it’s also about the consolations of stories and the balm they have provided for millenniums. It’s a wildly inventive novel that teems with life, straddles an enormous range of experience and learning, and embodies the storytelling gifts that it celebrates. It also pulls off a resolution that feels both surprising and inevitable, and that compels you back to the opening of the book with a head-shake of admiration at the Swiss-watchery of its construction. “Let me start big. The mission of the Claremont Institute is to save Western civilization,” says Ryan Williams, the organization’s president, looking at the camera, in a crisp navy suit. “We’ve always aimed high.” A trumpet blares. America’s founding documents flash across the screen. Welcome to the intellectual home of America’s Trumpist right.

“Let me start big. The mission of the Claremont Institute is to save Western civilization,” says Ryan Williams, the organization’s president, looking at the camera, in a crisp navy suit. “We’ve always aimed high.” A trumpet blares. America’s founding documents flash across the screen. Welcome to the intellectual home of America’s Trumpist right. Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies.

Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies. In the last few years, I have had dozens of conversations with leaders of companies and nonprofit organizations about the illiberalism that is making their work so much harder. Or rather, I should say I’ve had one conversation—the same conversation—dozens of times, because the internal dynamics are so similar across organizations. I think I can explain what is now happening in nearly all of the industries that are creative or politically progressive by telling you about what happened to American universities in the mid-2010s. And I can best illustrate this change by recounting the weirdest week I ever had in my 26 years as a professor.

In the last few years, I have had dozens of conversations with leaders of companies and nonprofit organizations about the illiberalism that is making their work so much harder. Or rather, I should say I’ve had one conversation—the same conversation—dozens of times, because the internal dynamics are so similar across organizations. I think I can explain what is now happening in nearly all of the industries that are creative or politically progressive by telling you about what happened to American universities in the mid-2010s. And I can best illustrate this change by recounting the weirdest week I ever had in my 26 years as a professor. America’s frustrating inability to learn from the recent past shouldn’t be surprising to anyone familiar with the history of public health.

America’s frustrating inability to learn from the recent past shouldn’t be surprising to anyone familiar with the history of public health.  In case we wonder why not all of us have healthy, sustaining, lifelong friendships, this issue offers some answers to the riddle of why and how friendships, begun in such pleasure and good faith, can derail so catastrophically.

In case we wonder why not all of us have healthy, sustaining, lifelong friendships, this issue offers some answers to the riddle of why and how friendships, begun in such pleasure and good faith, can derail so catastrophically. The United States began bombing the border zone, then known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), in 2004, ostensibly to combat al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It has bombed the area at least 430 times, according to the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalists, and killed anywhere between 2,515 to 4,026 people.

The United States began bombing the border zone, then known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), in 2004, ostensibly to combat al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It has bombed the area at least 430 times, according to the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalists, and killed anywhere between 2,515 to 4,026 people. The term ‘atheist’ can be just as ambiguous as ‘religious’ and ‘God’. In the 17th century, it was essentially an all-purpose word used against anyone whose view of God departed from orthodoxy – much in the way that ‘communist’ was (and is) used in the USA to cast aspersion on political opponents (and much in the way that ‘Spinozist’ was used in the early modern period after Spinoza’s works were posthumously published and condemned). But Spinoza does not only dismantle the orthodox notion of a personal God, which he regards as a source of human misery. He also famously refers to ‘God or Nature’ (Deus sive Natura), which suggests that God is nothing but nature, and that ‘God’ can broadly be construed to refer both to the visible cosmos and to the unseen but fundamental power, laws and principles that govern it. And this, to me at least, looks like true atheism. In Spinoza’s view, all there is is nature. There is no supernatural; there is nothing that does not belong to nature and that is not subject to its causal processes.

The term ‘atheist’ can be just as ambiguous as ‘religious’ and ‘God’. In the 17th century, it was essentially an all-purpose word used against anyone whose view of God departed from orthodoxy – much in the way that ‘communist’ was (and is) used in the USA to cast aspersion on political opponents (and much in the way that ‘Spinozist’ was used in the early modern period after Spinoza’s works were posthumously published and condemned). But Spinoza does not only dismantle the orthodox notion of a personal God, which he regards as a source of human misery. He also famously refers to ‘God or Nature’ (Deus sive Natura), which suggests that God is nothing but nature, and that ‘God’ can broadly be construed to refer both to the visible cosmos and to the unseen but fundamental power, laws and principles that govern it. And this, to me at least, looks like true atheism. In Spinoza’s view, all there is is nature. There is no supernatural; there is nothing that does not belong to nature and that is not subject to its causal processes. “Normal behavior and physiology depends on a near 24-hour circadian release of various hormones,” said Jeff Jones, who led the study as a postdoctoral research scholar in biology in Arts & Sciences and recently started work as an assistant professor of biology at Texas A&M University. “When hormone release is disrupted, it can lead to numerous pathologies, including affective disorders like anxiety and depression and metabolic disorders like diabetes and obesity.

“Normal behavior and physiology depends on a near 24-hour circadian release of various hormones,” said Jeff Jones, who led the study as a postdoctoral research scholar in biology in Arts & Sciences and recently started work as an assistant professor of biology at Texas A&M University. “When hormone release is disrupted, it can lead to numerous pathologies, including affective disorders like anxiety and depression and metabolic disorders like diabetes and obesity. Urging the German people to “stop the steal,” Donald J. Trump claimed that he was elected Chancellor of Germany over the weekend. Trump said that, once the official vote tallies have been recounted, it will be clear that he won the German election by a “landslide.” Reflecting on his purported win, Trump said,

Urging the German people to “stop the steal,” Donald J. Trump claimed that he was elected Chancellor of Germany over the weekend. Trump said that, once the official vote tallies have been recounted, it will be clear that he won the German election by a “landslide.” Reflecting on his purported win, Trump said, Dave Eggers’s newest book,

Dave Eggers’s newest book,  In the question to understand the biology of life, we are (so far) limited to what happened here on Earth. That includes the diversity of biological organisms today, but also its entire past history. Using modern genomic techniques, we can extrapolate backward to reconstruct the genomes of primitive organisms, both to learn about life’s early stages and to guide our ideas about life elsewhere. I talk with astrobiologist Betül Kaçar about paleogenomics and our prospects for finding (or creating!) life in the universe.

In the question to understand the biology of life, we are (so far) limited to what happened here on Earth. That includes the diversity of biological organisms today, but also its entire past history. Using modern genomic techniques, we can extrapolate backward to reconstruct the genomes of primitive organisms, both to learn about life’s early stages and to guide our ideas about life elsewhere. I talk with astrobiologist Betül Kaçar about paleogenomics and our prospects for finding (or creating!) life in the universe. “Leave? Certainly not. This Brit is staying” wrote journalist Stephen Vines in July 1997. Vines had given up his full-time position at the Observer in London to be stationed in Hong Kong on a part-time basis in 1987. At the time of the Handover, Vines had been living and working in Hong Kong as a journalist and businessman for ten years. He had faith in the people of Hong Kong, in the energy and audacity of the city. He believed that it was “foolish to jump before being pushed,” referring to those who had made plans to leave the city before the governance of the territory was returned to China. Vines kept his resolution and stayed in Hong Kong for another 24 years, constantly reporting on the business, finance, and politics of this city for a wide range of local and international media outlets. In 2021, he paid homage to the people of Hong Kong with his new book, Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong and the World’s Largest Dictatorship. In August, two months after the book’s publication, Vines ended his 34-year-long sojourn in the city and departed for London.

“Leave? Certainly not. This Brit is staying” wrote journalist Stephen Vines in July 1997. Vines had given up his full-time position at the Observer in London to be stationed in Hong Kong on a part-time basis in 1987. At the time of the Handover, Vines had been living and working in Hong Kong as a journalist and businessman for ten years. He had faith in the people of Hong Kong, in the energy and audacity of the city. He believed that it was “foolish to jump before being pushed,” referring to those who had made plans to leave the city before the governance of the territory was returned to China. Vines kept his resolution and stayed in Hong Kong for another 24 years, constantly reporting on the business, finance, and politics of this city for a wide range of local and international media outlets. In 2021, he paid homage to the people of Hong Kong with his new book, Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong and the World’s Largest Dictatorship. In August, two months after the book’s publication, Vines ended his 34-year-long sojourn in the city and departed for London.