Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack newsletter Hinternet:

What is weather? Its etymology is not, as one may have hoped, connected to “whether”, as in “that which may be either one way, or the other” —“Whether the picnic is on or not depends on whether it rains”—, though both words have equally fascinating Germanic pedigrees. The modern German Wetter originally described the sort of ferocious wind you might encounter at a mountain peak, and later took on the primary connotation of “bad weather”, or, as is said in German, Unwetter, where the prefix that ordinarily signifies negation or absence, Un-, comes instead to indicate intensification (as in Untier — seemingly “non-animal” but literally “monster”, or Unkraut — seemingly “non-herb” but literally “weed”). At the outset then we may say that weather, strangely, is something the negative instances of which are also its paradigm instances. Yet the German and English words for “weather” are outliers among European languages, while far more commonly the term that is used is the same as the word for “time”: French le temps, Romanian timpul (or the variant Slavic-rooted vremea); even the Finno-Ugric pocket of Hungary calls both time and weather by the same word: idő. Already from this lexical tour we may infer that at some earlier stage what we today call “weather” was conceptualized primarily in a phenomenological sense, as the most basic experience of “in-the-world-ness”. Yet the overlapping history of these two concepts, time and weather, should only make us wonder at the profoundly different connotations each would come to have in late modernity.

What is weather? Its etymology is not, as one may have hoped, connected to “whether”, as in “that which may be either one way, or the other” —“Whether the picnic is on or not depends on whether it rains”—, though both words have equally fascinating Germanic pedigrees. The modern German Wetter originally described the sort of ferocious wind you might encounter at a mountain peak, and later took on the primary connotation of “bad weather”, or, as is said in German, Unwetter, where the prefix that ordinarily signifies negation or absence, Un-, comes instead to indicate intensification (as in Untier — seemingly “non-animal” but literally “monster”, or Unkraut — seemingly “non-herb” but literally “weed”). At the outset then we may say that weather, strangely, is something the negative instances of which are also its paradigm instances. Yet the German and English words for “weather” are outliers among European languages, while far more commonly the term that is used is the same as the word for “time”: French le temps, Romanian timpul (or the variant Slavic-rooted vremea); even the Finno-Ugric pocket of Hungary calls both time and weather by the same word: idő. Already from this lexical tour we may infer that at some earlier stage what we today call “weather” was conceptualized primarily in a phenomenological sense, as the most basic experience of “in-the-world-ness”. Yet the overlapping history of these two concepts, time and weather, should only make us wonder at the profoundly different connotations each would come to have in late modernity.

More here.

It is more than 150 years since scientists proved that

It is more than 150 years since scientists proved that  Whenever there’s a leak of documents from the remote islands and obscure jurisdictions where rich people hide their money, such as this week’s release of the

Whenever there’s a leak of documents from the remote islands and obscure jurisdictions where rich people hide their money, such as this week’s release of the  Hip-hop artist Childish Gambino (aka actor

Hip-hop artist Childish Gambino (aka actor  Not long after I moved into my first apartment, I started keeping an archive.

Not long after I moved into my first apartment, I started keeping an archive. Jonathan Franzen, the novelist who has been lauded and reviled as few figures in contemporary American letters ever are,

Jonathan Franzen, the novelist who has been lauded and reviled as few figures in contemporary American letters ever are,  Aaron Benanav in The Nation (Illustration by Tim Robinson):

Aaron Benanav in The Nation (Illustration by Tim Robinson):

Justin Sandefur over at the Center for Global Development:

Justin Sandefur over at the Center for Global Development: Yakov Feygin in Noema (image by Roman Bratschi for Noema Magazine):

Yakov Feygin in Noema (image by Roman Bratschi for Noema Magazine): David McDermott Hughes in Boston Review:

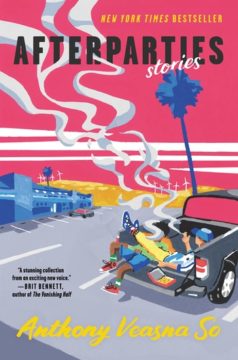

David McDermott Hughes in Boston Review: Afterparties is haunted by lateness, not only because it arrives after the premature death of its author, but also because it is a work of Cambodian American literature. “I very much feel that I come from a Cambodian-American world, not really an American one . . . so I find it important for my work to reflect that,” So said in a 2020 interview. In contrast to Asian American writing by those of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean descent (what So might refer to as “mainstream East Asians” in “The Shop”), Cambodian American writing is a relatively newer and more minor literature. (“We’re minorities within minorities,” goes So’s own self-description in his posthumous essay “Baby Yeah.”) There was a relative absence of Cambodian American communities until the late 1970s, following the genocide and the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act; there is now also a deficit of Cambodian writing and writers, because the Khmer Rouge annihilated Cambodian society by targeting its intellectuals and artists (libraries and schools were demolished, books burned, teachers murdered). The aftershocks of genocidal loss permeate the writing of the Cambodian diaspora, as the deliberate obliteration of their literature makes the work of contemporary writing both more necessary and difficult. For the children of Cambodian refugees, this work is even harder: How do you write the stories of those whose stories were systematically destroyed?

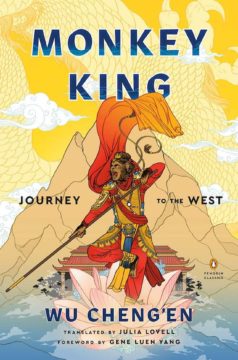

Afterparties is haunted by lateness, not only because it arrives after the premature death of its author, but also because it is a work of Cambodian American literature. “I very much feel that I come from a Cambodian-American world, not really an American one . . . so I find it important for my work to reflect that,” So said in a 2020 interview. In contrast to Asian American writing by those of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean descent (what So might refer to as “mainstream East Asians” in “The Shop”), Cambodian American writing is a relatively newer and more minor literature. (“We’re minorities within minorities,” goes So’s own self-description in his posthumous essay “Baby Yeah.”) There was a relative absence of Cambodian American communities until the late 1970s, following the genocide and the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act; there is now also a deficit of Cambodian writing and writers, because the Khmer Rouge annihilated Cambodian society by targeting its intellectuals and artists (libraries and schools were demolished, books burned, teachers murdered). The aftershocks of genocidal loss permeate the writing of the Cambodian diaspora, as the deliberate obliteration of their literature makes the work of contemporary writing both more necessary and difficult. For the children of Cambodian refugees, this work is even harder: How do you write the stories of those whose stories were systematically destroyed? Third, Monkey King accentuates one of the major appeals of the novel — its humor — with embellishments made by the translator in three main ways: dialogue, the culture of the immortal society, and the technicality of magic. Monkey is nothing without his complete disregard for formality, even (or especially) as he interacts with those perching at the top of the deities’ hierarchical system. He evokes both childish innocence and rebellious boldness. The English edition takes this characteristic and runs with it, tweaking a word choice here and perfecting a repartee there, in line with the lighthearted tone of the original. I should mention also that Lovell excels at spicing up the insults exchanged between Monkey and his enemies. One of the spirits sent to subdue Monkey threatens his monkey kingdom, “The merest whisper of resistance and we’ll turn the lot of you into baboon butter” — you will not find “baboon butter” in the original version.

Third, Monkey King accentuates one of the major appeals of the novel — its humor — with embellishments made by the translator in three main ways: dialogue, the culture of the immortal society, and the technicality of magic. Monkey is nothing without his complete disregard for formality, even (or especially) as he interacts with those perching at the top of the deities’ hierarchical system. He evokes both childish innocence and rebellious boldness. The English edition takes this characteristic and runs with it, tweaking a word choice here and perfecting a repartee there, in line with the lighthearted tone of the original. I should mention also that Lovell excels at spicing up the insults exchanged between Monkey and his enemies. One of the spirits sent to subdue Monkey threatens his monkey kingdom, “The merest whisper of resistance and we’ll turn the lot of you into baboon butter” — you will not find “baboon butter” in the original version. Let’s talk about fear, health and why so many of us have decided that sitting in front of the

Let’s talk about fear, health and why so many of us have decided that sitting in front of the